Photo ©

Bellarmine University

As a journalist and a mother in an Arab American family, I have long been concerned about “othering,” dividing the world between “us” and “them,” especially when stereotypes of “them” are too often “backward” or “dangerous.” Consequently, as a teacher in higher education, I have aimed to teach empathy and intercultural understanding.

One of the best ways to help students broaden their worldview and see from other perspectives is to introduce them to young people in other parts of the world. Fortunately, developments in technology over the past 30 years offer ways to bring geographically and culturally diverse students together, making international experience accessible to more than just those who can afford to study abroad.

Staying connected

To prepare to move to Lebanon in 2009 for a teaching position at Rafik Hariri University, I decided to take a graduate course in online teaching at Marquette University. I thought it would give me tools to stay connected to Marquette, where I had been an adjunct faculty member for 20 years. While it did help me teach online courses for MU, I had no inkling about the other wonderful opportunities it would create.

At the time, internationally collaborative classes were rare and have continued to be until recently. The pandemic has pushed a proliferation in cross-border teaching collaborations as universities seek out ways to internationalize the university experience for students in a world where travel is on hold.

During my first visit back to the U.S., Dr. Claire Badaracco, a colleague in MU’s College of Communication, told me about a course she taught about the media’s role in conflict. We talked about how exciting it would be to bring together students from the Middle East and the middle of America to discuss cultural identity and media portrayals, and to analyze media reports of current events. Those conversations led us to create the first fully collaborative transnational blended class between a Lebanese and U.S. university.

Claire retired from Marquette and moved home to Kentucky, where she taught courses at Bellarmine University, which had recently invested in state of the art teleconference capabilities. That created the opportunity in 2012 for us to launch our collaborative class.

Inside collaborative online international learning

“I’ve got a question for Beirut,” said a young man projected on a large screen at the front of my classroom at Rafik Hariri University. “What’s it like to have that conflict in your backyard?”

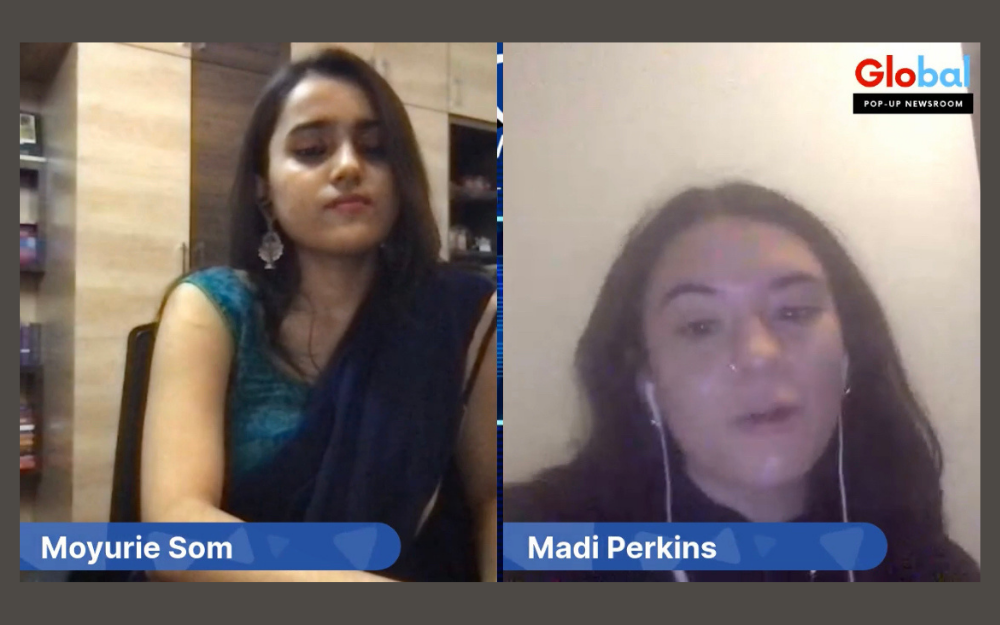

A web camera pointed at 12 RHU students and a microphone sat in the center of the conference table. It was 5 p.m and dark outside, but the morning sun shone through the windows of the Bellarmine University classroom we saw on the screen. That classroom was in Louisville, Kentucky — nearly 6,198 miles away. A senior at Marquette who audited the course also appeared on the split screen.

Eager to dispel stereotypical images of Lebanon as a nation littered with bombed-out buildings and piles of rubble, my student Osamah Dabdoub responded, “Don’t get the wrong idea. We are having fun. We are partying, probably more than you.”

Our students communicated through video-conferencing, social media and an online discussion board. We invited expert speakers and journalists from around the world into our video conferences.

The next semester our classes were joined by a graduate class from the Jordan Media Institute in Amman. Many of the JMI students were working in Jordan’s broadcast news outlets. They enriched our experience by talking about how they selected and produced their stories.

One thing leads to another

The following year, Claire and I spoke at an educator’s conference in New York about our novel experiment. We met other people who were also doing what grew to be called “collaborative online international learning.”

I sought out other colleagues at Marquette who might be partners in future projects. Dr. Gee Ekachai and Dr. James Scotton were both interested in exploring possibilities.

Gee shared her valuable “Key Pal” project in which students were paired with international partners to learn about each other’s lives, interests and perspectives. We connected our students through social media. Jim’s international media class met with mine through teleconferences for discussions on how the news media in each country covered the same current events.

Jim invited me to participate in a pre-conference panel for the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, a major international organization for educators in the field. That presentation, as well as a hiking trip in Lebanon, led to connections with educators all over the world who invited me to share in their projects and vice versa.

Classes from Rafik Hariri University, Marquette University and Bellarmine University participate in an international teleconference.

As a result, my students at RHU and later at MU have participated in global projects with students on every continent of the world, such as PopUpNewsroom, Global News Relay and GENII, the Global E-News Immersion Initiative. By reporting on poverty, shelter, women’s rights, the climate crisis and other themes, students can compare how these issues play out across the world.

When I moved back to the United States in 2018, I began seeking collaborators in Lebanon. Dr. Maria Bou Zeid, the chair of the Department of Media Studies at Notre Dame University in Lebanon, and I have partnered on extensive projects for the past three years. Our students have met regularly in small groups through Facebook and video conferences to learn about each other’s culture and circumstances.

I also had the privilege of working with Dr. Claudia Kuzman at the Lebanese American University. She shared a project we implemented called the Media Summit, a video conference in which our students taught each other about how media operates in their respective countries.

Being involved in these international collaborations has been among the most rewarding experiences of my teaching career. They have allowed me to build relationships with colleagues from around the world while witnessing students develop empathy and cross-cultural understanding.

Why does it matter?

Preparing students to be global citizens with intercultural communication skills and cultural sensitivity has become a focal point for higher education. Whether graduates will travel abroad or work in multi-national companies, today’s youth are more likely to come into direct contact with people from different parts of the world than any generation before.

While these digital natives can navigate the web with ease, this will not prepare them for global encounters. In fact, the ability to empathize is on the decline. University of Michigan research professor Sara Konrath, Ph.D., found that among American university students, empathy declined a whopping 48 percent from 1979 to 2009. We are living in what has been coined “The Age of Anger,” one characterized by political polarization and hardened group identities.

Online interactions in an educational setting create spaces to counter misunderstandings and stereotypes, and to teach students how to “be in someone else’s shoes.” Developing empathy is “transformational learning” that is best accomplished through experiences with others, according to research fellow Darla Deardorff, Ph.D., of Duke University.

For me, it’s personal

When Aziz and I married, we planned to give our Arab-American children both cultures. We want them feel like natives in both worlds; to be able to speak Arabic and English; to feel comfortable kissing cheeks and hugging; to enjoy hamburgers and falafels; and to appreciate Beethoven, the Beatles and Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum.

We want them to have the security of being part of a tight-knit extended family in which all the joys and sorrows are shared. At the same time, we hope they learn the lessons passed down in America: that they are free to pursue their individual dreams and have personal responsibility for what they make of themselves.

But giving them this experience does not just depend on what they learn; it also requires creating a welcoming world.

One of the most common comments I hear from students in the U.S. and in the Middle East about their international partners in these educational projects is that “we have so much in common, much more than I expected.”

I think that is a great start. I feel privileged to be a part of it and am hopeful about the benefits this growing movement in education can bring.