Aasim Padela, MD, MSc, discussed his team’s research on discrimination against Muslim physicians during the “Advancing Equity for Muslim Physicians in the Healthcare Workforce” webinar.

“In 2023, we are at a time where a lot of medical students are transitioning to resident life, from a student protected population to employees in our workplace,” Aasim I. Padela, M.D., professor of emergency medicine, bioethics and the medical humanities at the Medical College of Wisconsin, commented to an online audience. Imagining a hypothetical student, he asked, “What will her experience be? Specifically, how will her patients respond to her? How will her colleagues treat her when she enters the profession? How will the workplace environment shape her? And what will her career look like?”

If she’s Muslim, she’ll likely face increasing discrimination, according to a decade of research by the Initiative on Islam and Medicine, where Padela serves as both chairperson and director.

Padela spoke Friday in the national webinar “Advancing Equity for Muslim Physicians in the Healthcare Workforce,” co-hosted by Initiative on Islam and Medicine, the Tanenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding, Medical College of Wisconsin and American Muslim Health Professionals. Panelists reviewed research on religious discrimination and discussed the impact it has on professional and psychological outcomes for Muslim physicians.

The webinar coincided with the release of the Initiative on Islam and Medicine’s policy report that chronicles Muslim physicians’ experiences and offers recommendations to improve religious diversity, equity and inclusion in the healthcare workforce. The research supporting the policy report found that a greater proportion of Muslim physicians experience discrimination at work now than a decade ago.

Muslims are strongly represented in healthcare professions

Muslims make up just over 1% of the total population in the United States, according to a 2017 study from the Pew Research Center. A number so small, “many Americans have never knowingly met a Muslim,” noted panelist Meira Neggaz, executive director of the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, an institution seeking to develop objective, solution-oriented research about challenges and opportunities facing American Muslims.

Meira Neggaz, executive director, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding

“Despite the relatively small size of the Muslim population in the country, Muslims play a really important role in the medical field and in our healthcare system,” Neggaz said. She cited Michigan, where Muslims make up just under 3% of the state’s population, yet more than 15% of the licensed medical doctors in the state. Additionally, Muslims are 10% of Michigan’s pharmacists and 7% of its dentists, she said.

Not only are the percentages of Muslims in medicine high, their accomplishments and impacts are significant, she noted. “Muslim doctors are not simply practicing medicine. They are often responsible for making significant innovations and improvements across the entire medical field.” She cited examples of individuals who developed innovative treatments and Muslim doctors who provide a lot of charitable medical care.

“We’ve seen similar patterns to this (Michigan) case study in New York City, and, most likely, we will find this nationally,” she said. “So, meeting the needs of Muslim physicians and providing an equitable, non-discriminatory workplace is essential, not just for the individual Muslim physicians themselves, but for our healthcare system.”

Yet, discrimination in healthcare is “both interpersonal and institutional,” she said. “It takes place between people in informal interactions but is also structural and institutionalized.”

Groundbreaking research

Padela’s research in 2013 was the first to examine religious identity and workplace discrimination against American Muslim doctors. A nationwide survey found nearly half of physicians identifying as Muslim felt more scrutiny at work compared to their peers, and nearly one in four said they faced religious discrimination during their careers. Almost 10 percent of the physicians said patients had refused their care because of their Muslim identity, they reported.

In 2021, Padela repeated the quantitative research and also added a qualitative component, conducting interviews to better understand the context of participants’ responses.

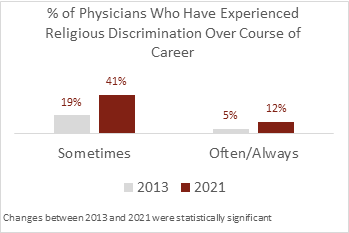

Graphics courtesy of the Initiative on Islam and Medicine

Since national databases of physicians do not collect religious affiliation, Padela’s team drew on the membership roster of national clinician organizations that explicitly integrate religious identity. In 2013, a random sample was taken from the Islamic Medical Association of North America. In 2021, they drew a convenience sample from IMANA, the American Muslim Health Professionals and the U.S. Muslim Physician Network. (See more details about methodology here.)

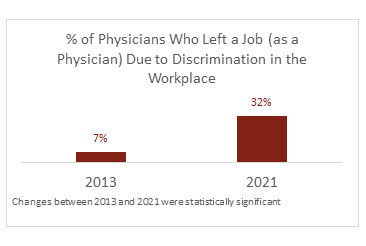

A comparison of results shows that over the past 10 years, an increased number of Muslim physicians are experiencing religious discrimination, job turnover and having patients refuse care.

- In 2013, 19% of Muslim physicians participating in a national survey reported sometimes experiencing discrimination in the workplace, while 5% reported often or always encountering discrimination during their careers.

- In 2021, 41% of Muslim physicians participating in a national survey reported sometimes experiencing religious discrimination in the workplace, while 12% reported often or always experiencing discrimination.

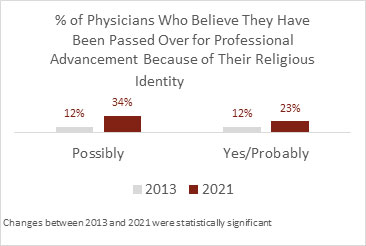

- In 2013, 24% of Muslim physicians participating in a national survey reported they have been passed over for professional advancement because of their religion.

- In 2021, 57% of Muslim physicians participating in a national survey reported they have been passed over for professional advancement because of their religion.

- In 2013, 7% of Muslim physicians participating in a national survey reported leaving a job due to discrimination.

- In the 2021 survey, 32% of Muslim physicians reported leaving a job due to discrimination.

Graphics courtesy of the Initiative on Islam and Medicine

The research also addressed whether respondents agreed that their workplace accommodates for their religious identity, on such matters as allowing time and an appropriate place for prayer during a workday, accommodation of fasting during Ramadan and time off for celebrating religious holidays. In both 2013 and 2021, about three-fourths of the respondents agreed their workplace did make accommodations. However, interviews revealed that “notions of accommodation focused on their own initiatives rather than the institutional outreach.”

Psychological toll on Muslim physicians

“The impact of this obviously may take a toll on mental health and anxiety of people experiencing these issues,” Neggaz said. “We know from our research that after the 2016 election, when there was a lot of heated political rhetoric about Muslims, there was a significant amount of stress and anxiety and fear for personal safety. Most notably, almost half of Muslim women and more than 30% of Muslim men feared for their personal or family safety. A sizable number felt stress and anxiety to the point of possibly seeking mental health support.”

He noted that other researchers have found that groups who have been targeted or hear negative things about their group can internalize those negative aspects. “And this can have a huge effect on mental health, on self-esteem, identity, performance and motivation.

“And in our own study of Muslim healthcare workers last year, where we looked a year into COVID, we examined psychological distress, distress discrimination and sources of that stress as well as coping mechanisms. And what we found is that 47% of the sample reported at least one form of discrimination during the period, including anti-Muslim bias. This form of discrimination was associated with a higher risk of psychological distress, including depression and anxiety.”

Graphics courtesy of the Initiative on Islam and Medicine

Padela recalled a colleague who in 2016 wrote a commentary about her experiences as a resident. “She went to Harvard and to Yale, and she went to residency at a very elite medical school. She thought she had done the sort of work that would give her a golden ticket to the American dream, that the training would shield her from racism, bigotry and discrimination. Still she heard things from patients like, “Why do you wear that thing on your head anyway? Another patient said, ‘I don’t want someone taking care of me with that on, pointing to her hijab.” That is the racism she carried with her through her residency training into her professional life.”

Interview participants recommend improvements

In 2021, interview participants recommended ways healthcare systems could better address their needs as Muslim physicians. They called for education and for policy intervention in light of how diversity, inclusion and equity programs often overlook the religious dimension of physicians’ identity. They recommended programs directed at all levels of the workforce that center on Muslim identity to create awareness of the challenges and needs of Muslim physicians.

Regarding policy interventions, many healthcare systems do not address religious accommodations. For example, there are no policies to facilitate time off to pray or regarding religious attire. Written policies would reduce the burden Muslim physicians face in trying to obtain accommodations, they said.

Beyond these overarching recommendations, the following were suggested:

- Providing support and designated spaces for daily and Friday prayer.

- Acknowledging the practice of Ramadan fasting and Islamic holidays.

- Creating policies to protect Muslim dress code in the workplace.

- Recognizing Muslim dietary preferences and restrictions.

- Instituting a faith community liaison position.

- Medical education should account for religious identity.