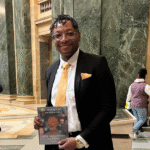

Ruwa Romman (left), representative-elect of Georgia’s 97th and Nabeela Syed, representative-elect of Illinois’s 51st District (COURTESY OF RUWA ROMMAN CAMPAIGN; NABEELA SYED CAMPAIGN)

A record number of Muslim women ran for office in 2022 — and they won. The election cycle made history with 153 Muslim candidates on the general ballot, per a report released by Jetpac Resource Center and the Council on American-Islamic Relations. Sixty-one percent of Muslim women candidates won, compared with 56 percent of Muslim men. Mauree Turner, the only nonbinary Muslim in the midterm elections, won a second term in the Oklahoma legislature. It’s a notable shift in a country with a deep history of Islamophobia.

Sahar Aziz, professor of law at Rutgers University and author of “The Racial Muslim: When Racism Quashes Religious Freedom,” attributed this rise in representation to two factors: immigration history and differing reactions to Islamophobic society.

Aziz said these gains in representation are partly due to a “generational coming of age” that is common with new immigrant populations. Over 70 percent of American Muslims are immigrants or descendants of immigrants who came to the United States after national origin quotas were abolished in 1965, making many Muslims second- or third-generation Americans.

“With those changes, you will have people who are now born and raised in the U.S., educated only in the U.S., their parents were born and raised in the U.S.,” Aziz said. “So they have the social network, human capital and the familiarity with the society as a political system that [now] they’re much better equipped to run for office.”

With these generational changes come differing reactions to prejudice. In the face of so many Muslim lives unfairly changed and destroyed after the September 11, 2001, attacks, Ruwa Romman saw her parents’ generation become very protective of their community. Heightened surveillance and deportations had a “chilling effect,” spurring many to avoid attention and to stay quiet.

But young Muslims are pushing back and speaking up. Romman is 30, and representative-elect of Georgia’s 97th District. “As my generation grew older, we thought, one, why are we all collectively agreeing to being seen as a guilty party when we weren’t? And two, we have just as much right to engage in this political process as everybody else,” she told The 19th.

Mohammed Missouri, executive director of Jetpac Resource Center, a nonprofit working to empower Muslim public leaders, said that President Donald Trump’s vocal and direct attacks on Islam were the final straw for many people who had felt ostracized for years. “People felt like there was only one way to truly show that not only do we belong here — we’re Americans, just like everyone else. And that’s by getting engaged in politics, and making sure that people can’t make decisions about us without us being part of that decision-making process.”

Nabeela Syed was a senior in high school when Trump was elected into office. Hearing the former president’s hate-filled rhetoric, and his subsequent ascension to the presidency, made her question whether she truly belonged. It wasn’t the first time she had been called a terrorist or treated differently, but it marked a turning point in her life.

“In my heart, I knew I did belong,” Syed said. “And that’s why I turned towards politics.”

Syed won her race to represent Illinois’s 51st District against a Republican incumbent in November. The 23-year-old will be the first Muslim in the state legislature and the youngest-ever member of the State Assembly.

“To go from having no representation to having representation with someone who’s very visibly Muslim, wears a hijab on her head, I think, is very exciting for people in the community,” she said.

Many Muslim women candidates were already established leaders before seeking elected office. Romman worked as a field organizer for Asian American Advocacy Fund and the Georgia Muslim Voter Project, and she ran for office at the urging of her community after a journalist overstated her electoral ambition in an article. Nabilah Islam, senator-elect for Georgia’s 7th District, has been an activist and organizer for over a decade. Her experiences of “otherism” motivated her to support marginalized candidates and make sure people who understood the lived experiences of her communities were serving in office.

Islam first sought office herself in 2020, losing the Democratic primary for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Seeing Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar elected in 2018 inspired her to run. “It awakened a lot of people in the Muslim community,” Islam said. “It showed us we are electable and worthy of being a part of this democratic process.”

“You can’t be what you can’t see,” she said. “When I ran the first time I had multiple people tell me, ‘Because you did it, I feel like I can run too.’”

Romman also commented on the importance of representation. “Seeing that Rashida [Tlaib] was a Palestinian who got elected to Congress by a predominantly not-Arab group of people was the first time that I ever thought that I could have a role in politics that wasn’t just hidden as much as possible,” she said.

Romman and Syed both spoke kindly of their communities, emphasizing the good experiences they had while campaigning. But it hasn’t all been roses. Supporters of Romman’s opponent called her a terrorist and attacked her policies as un-American. Throughout her time in politics, Islam has been called a terrorist, and — despite being born in the United States — was told to “go back home” and that she isn’t American.

The struggles each Muslim candidate can face are based on many factors — such as immigration status, accent, age, name and, for women, whether they wear a hijab. There isn’t research specifically on the challenges faced by Muslim women versus other political candidates in the United States, Aziz said.

But we can assume at least one thing, she said: “Regardless of what she does, how she dresses, or what her campaign platform is, the audience that she’s engaging with has been primed for the last 20 years to have negative stereotypes about Islam, about Arabs, and about women who are Muslim and/or Arab.”

Many of these stereotypes come from post-9/11 news coverage and media depictions, as well as inflammatory rhetoric by politicians. Common Islamophobic tropes are associated with terrorism and accusations of anti-Semitism, particularly in the context of Israeli foreign policy.

But Islamophobia affects people differently based on their gender too, Aziz explained. Muslim men are presumed to be violent and planning terrorist acts, while Muslim women are presumed to be aiding and abetting the violent acts of men, or seen as victims of that violence. As with many women of color running for office, Muslim women have to navigate intersectional identities relating to religion, ancestry, immigration and gender.

Aziz said that if Muslim women critique social or political events in Muslim-majority countries, their comments can weaponized to validate negative stereotypes of Muslim men. But if they try to add nuance to conversations about Islam or defend the civil rights of Muslims, “they’re accused of being apologists [or] that maybe they’re afraid to criticize their religion or criticize people in their religious community.”

Aziz also had lived experience on her expertise. She ran and won a seat on her local school board in 2020. She spoke with The 19th about her experience in her individual capacity, and not as a representative of the school board or as an elected official.

As a university professor who researches civil rights and women’s rights, she wanted to make a concrete difference in schools her children attended. She also wanted to run, as an Arab and a Muslim woman, because she believes in the power of representational democracy. She saw simply running as an accomplishment and was surprised when she won.

But after Aziz was elected, she saw people in her town attacking her not for issues related to the school board, but shamelessly linked to her identities. “That was a disturbing and enlightening experience to see the extent to which people’s bias was shamelessly explicit, and an outright attempt to sabotage the democratic process, and the business of oversight of school boards,” she said.

While visibility can bring heightened criticism, there is optimism, too: Islam said that the wins of Omar and Tlaib in 2018 inspired her and other Muslim women to run for office. “It showed me that the country was ready for representation that was bold and progressive,” she said.

“I just sincerely hope that these wins, both in Georgia and around the country, really show people that our world and our country is much more diverse and complicated than we give it credit for,” Romman said. “It’s the fact that if you do good work, and you’re invested in your community, your community will trust you to take care of them.”