With growing awareness of the importance of mental health nationally, we are also seeing a shift in American Muslim communities towards understanding mental health issues, not to mention recognition of our own Islamic contributions and legacy to this field. There are some mental health conditions, however, that continue to be marginalized in almost all Muslim spaces.

If you ask the average person here in the United States what they know about Muslims, chances are that one of the main things they will mention is that Muslims don’t drink alcohol. Substance use is indeed morally prohibited in Islam, but the fact that this particular prohibition sticks out as a defining characteristic of our faith community speaks to the seriousness with which many Muslims treat substance use. However, at times, it may also color the way that we treat members of our own Muslim communities who struggle with addictions.

The reality is that some Muslims use substances like alcohol and illicit drugs. This fact is documented not only through experiential knowledge of those struggling within our own communities but also through formal studies like the 2001 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study which showed that 46.6% of Muslim college students reported drinking alcohol in the past year.

In the medical world, substance use is defined as the use of a substance like alcohol or cannabis—in other words, drinking a beer or smoking weed. In contrast to Islamic rulings that take the stance of complete prohibition, the medical world doesn’t consider substance use to be a health issue if done in moderation. However, substance use can evolve into a substance use disorder if the substance use becomes unhealthy or dangerous—for example, binge drinking.

Substance use disorders, also called addictions, don’t depend on a person’s behaviors (i.e., drinking too much), but also on their genetics and changes in brain makeup as drug use continues. For this reason, addiction is not a failure of willpower to stop using substances. Rather, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, it is a type of brain disease that must be treated through a healthcare lens.

For Muslims, the story can be considerably more complicated. Even though substance use is morally prohibited in Islam, the fact is that some Muslims use substances and others go on to suffer from addictions. Addiction in the Muslim community is a shadow problem, likely because of the additive multiple stigmas—the stigma against mental illness, against substance use, and against engaging in a religiously prohibited action.

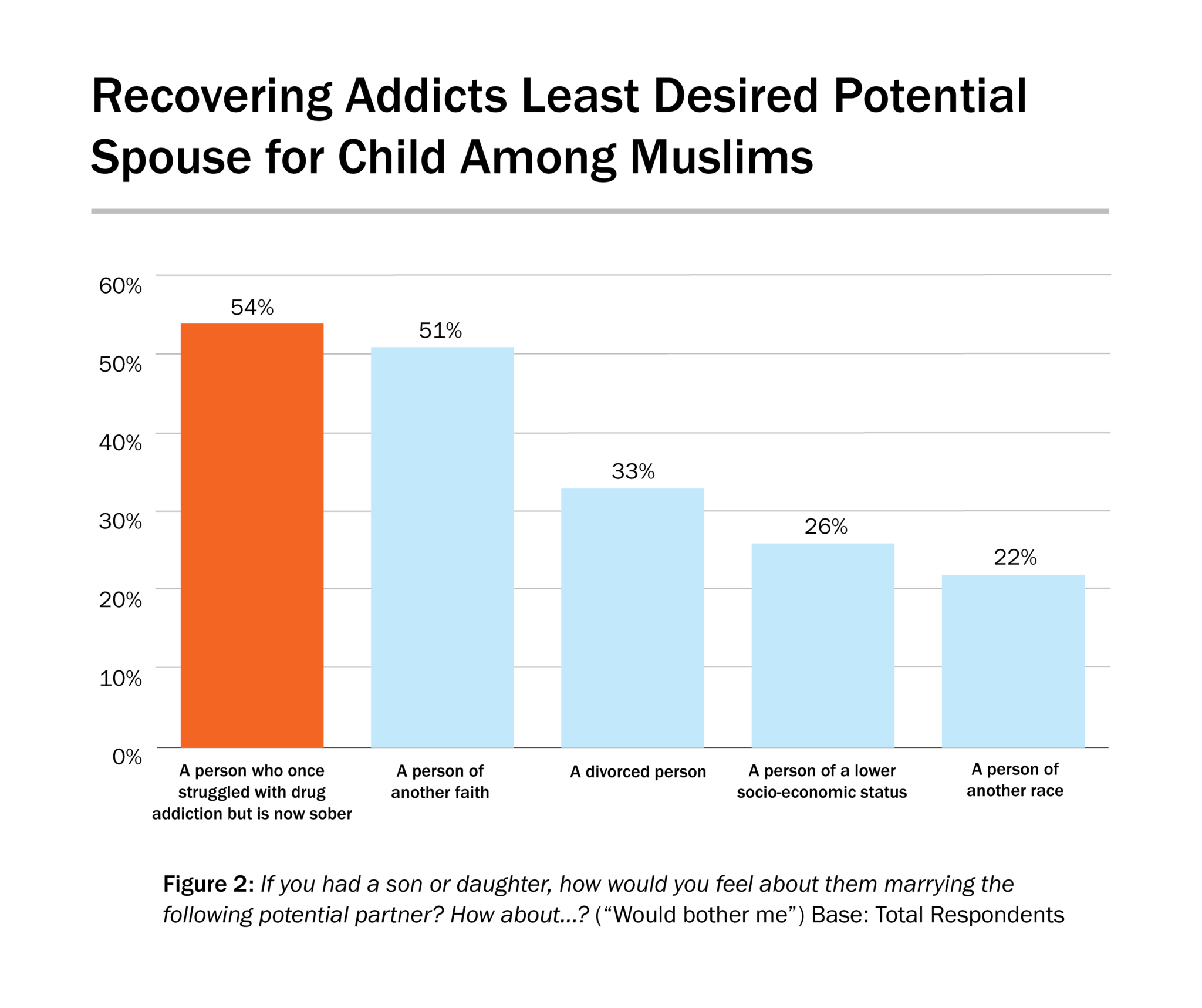

In fact, the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU) found through their 2020 Muslim Poll that 54% of American Muslims reported that those recovering from addictions are the least desirable spouse for a child, highlighting the stigma against them. Furthermore, many Muslims may hesitate to see addiction as a brain disease because they see the haram use of substances instead. For a Muslim dealing with an addiction, the experience is a double whammy—a problem on both the religious and the health fronts.

As Muslims, we must ask: how can we help those who are struggling?

The answer is multifaceted for tackling a problem like addiction, and we each have a different role to play. Clinical researchers like us at the Stanford Muslim Mental Health & Islamic Psychology Lab must help develop the literature on the American Muslim addiction experience so that we can better document and understand the problem. We are indeed actively doing so – our lab’s newest line of research is dedicated to the study of substance abuse in Muslim communities.

Community organizations like Maristan and its sister organizations must develop educational programs and training so that our community leaders are better poised to tackle this issue in their respective communities. Muslim religious leaders must find ways to discuss both the prohibition of substance use on the one hand and the Islamic mandate to help those struggling on the other.

Muslim centers must consider setting aside age-old stigmas and instead create healing spaces within their institutions that allow for faith-inspired recovery groups for those struggling and support groups for their loved ones. On an individual level, perhaps the most impactful step each of us can take is to challenge ourselves to view addiction as an experience deserving of mercy, empathy, compassion, and awareness—all of which are mandated by our faith.

By changing the way that we think about others in our ummah who are dealing with this experience, or any mental health struggle, we can make our communities more supportive places to heal. Ultimately, as believers, we all have the same goal: hayatan tayyiba, a good life (Quran 16:97) in this world, and a better life in the final abode.

On this World Mental Health Day, let us recognize that awareness and empathy may be our most powerful tools to accomplish this unified goal.