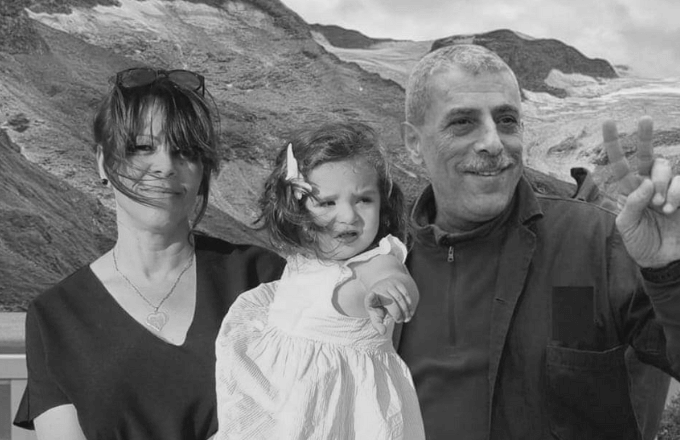

WALID DAQQAH (RIGHT), HIS DAUGHTER MILAD (CENTER), AND HIS WIFE SANA’ (LEFT). (PHOTO COURTESY OF THE FREE WALID DAQQAH CAMPAIGN)

When he was diagnosed with Myelofibrosis in 2022, Walid Daqqah knew that his life had entered its final years. ًWhat few could guess at the time is that a second life, outside the immediate social realm, had just begun.

Walid Daqqah probably knew it. He might even have symbolically predicted it. Twenty years before becoming a father, Walid chose the name of his unborn daughter — Milad, Arabic for “birth.”

“The name of Milad makes of my own name a complete sentence: Milad Walid Daqqa,” he said.

Milad Walid Daqqah, the four-year-old girl born to Walid and his wife Sana’ Salameh in 2020, became a national celebrity in Palestine shortly after coming to the world. On social media, Palestinians follow and comment on every detail of her life released by her mother, as if she were closely known to everyone.

Her story is the story of Palestinian resilience. But on a deeper level, Milad provides a physical window for us into the ongoing reality that her father had theorized and struggled against — the reality of a life lived between the teeth of occupation, a parallel reality.

Walid Daqqah died on April 7, 2024, in the Israeli Asaf Harofeh’ hospital. In his last six months, Walid was denied family visits and constantly transferred between the Ramleh prison clinic and the hospital, his feet and wrists always cuffed to the bed. His family, who hasn’t yet been handed his body, accused Israel of deliberate medical negligence. Israeli police banned the family from opening their home for mourners in accordance with Palestinian tradition, and Israel’s security minister publicly expressed regret that he had died a “natural” death.

By the time of his death, Walid was a public figure. He was known to Palestinians as an intellectual, an educator, a writer, a children’s author, and a leader. But Walid Daqqah’s story had a very troubled yet regular Palestinian beginning.

Walid was born in 1961 to a farmers’ family in the Palestinian town of Baqa al-Gharbiyah in ‘48 Palestine. He was born under the military rule that Israel had imposed on the Palestinians who had remained within its borders after the Nakba for almost twenty years.

In 1982, Walid was deeply impacted by the massacre of Palestinian refugees at Sabra and Shatila at the hands of Lebanese Israeli proxies enabled by the Israeli army. It was in this context that he decided to join the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

The following year, a PFLP cell abducted and later killed an Israeli soldier. The cell’s initial aim was to negotiate the release of Palestinian detainees for the soldier’s life. Israeli forces arrested Walid Daqqah in 1986 and accused him of belonging to the cell. He was later given a life sentence, which Israel later fixed in its law as 37 years. It was then that Walid’s life began its longest phase.

“I think that the life course of Walid is split in two; the social time, starting from his birth in 1961 until his arrest in 1984, and the ‘parallel time’ — from his arrest until this moment,” explains Abdul Rahim al-Shaikh, professor of Philosophy and Cultural Studies at Birzeit University and a friend of Walid Daqqah who wrote extensively about his work.

“Naturally, the first time extends into the second, and vice-versa, with a high flexibility on the level of his political, intellectual, and creative written production,” al-Shaikh told Mondoweiss. “Walid spent his life going back and forth between these two times, physically, intellectually, and spiritually.”

“You will never have an academic degree,” the head of the Israeli prison services once told Walid early on in his sentence, according to his wife Sana’ during an interview for Al-Araby Al-Jadeed’s podcast last year.

The deprivation of studying, just like that of having a family life, was later understood by Walid as a deliberate way of locking Palestinians out of the current, social time of their people, their country, and the rest of the world. Yet, Walid Daqqah was among the first Palestinians to fight for the right to education in Israeli prisons. In the early 2000s, Walid obtained a BA degree in political science, later followed by an MA degree. In 2014, he obtained a second MA degree in Israeli Studies.

By the time Walid Daqqah marked his first academic achievements and began to publish his written work, the Palestinian liberation movement had taken a critical turn following the signing of the Oslo accords in 1993 and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority the following year.

The Palestinian leaders’ commitment at Oslo was to “peace” negotiations over a limited authority in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. This meant for Walid Daqqah that the PLO, to which he belonged via the PFLP, “had given up on ‘48 Palestinians and by extension on ‘48 Palestinian prisoners,” says Abdul Rahim al-Shaikh.

In the midst of this political environment, Walid decided to join the Democratic National Assembly in 1996, a political party founded by Azmi Beshara in 1995 that participated in Israeli Knesset elections. It was one of the earliest political parties to be formed by ‘48 Palestinians after Israel allowed its “Arab citizens” to form their own parties.

It had been 13 years since Walid was first arrested, and he made his new political choices by adapting, like all Palestinians, to the new post-Oslo reality. He struggled to continue his studies, sharpen his writing skills, and win his fellow prisoners’ recognition as a leader. His family, meanwhile, still hoped for an early release as part of the negotiations process. At this moment, Sana’ Salameh entered his life.

“I come from a political household. My father and my uncle had been detainees in the occupation prisons, and the prisoners’ cause was a familiar topic at home,” Salameh tells Mondoweiss. “I was volunteering for a prisoners’ rights group called ‘Ansar al-Sajeen [Supporters of the Prisoner],’ and I wrote for a local newspaper called al-Sabbar, mainly about detainees and prisoners, although I was a translator, not a journalist.”

At the advice of the rights group’s director, Sana began visiting Palestinian prisoners, and she requested to visit Walid Daqqah. In the following months, Sana’ became Walid’s main confidant. He delegated prisoners’ support missions to her, including sending messages to families, completing legal procedures, and bringing clothes and food to jail, which Israel still allowed at the time.

“Walid turned out to be a trap,” Sana’ says jokingly. “He gave me so many missions to carry out that later one of the prisoners said that during those years, I did more work than three human rights groups together, and all on Walid’s instructions.”

In the following three years, Walid and Sana’s relationship evolved. They decided to formalize it in 1999. With the help of friends and Palestinian representatives at the Israeli Knesset, Walid and Sana’ obtained permission to celebrate their wedding in prison, in the presence of a few friends and family members — an unprecedented case that to this day has not been repeated.

“Walid is not a normal person, you don’t meet someone like him every day,” Sana’ says. “He is charismatic and fun, but at the same time very deep, and very reliable as a lover, a husband, a friend, or a cellmate. He is as faithful to his tiniest commitments as he is to his largest ones, and many who have met him have told me that Walid changed things in their character, made them translate this change in their lives.”

In 2002, following Israel’s siege and invasion of the Jenin refugee camp, Walid published Diaries of the Resistance in Jenin, a series of testimonies he had compiled from Palestinians he contacted in prison who had been a part of the Battle of Jenin during Israel’s Operation Defensive Shield. He documented every aspect of the event, including the life of the community under siege, the fighting tactics of the Israeli army, and the Palestinian resistance. The study became a reference for anyone seeking to examine Palestinian resistance in the Second Intifada.

At the same time, Walid and Sana’ engaged in a legal battle for conjugal visits — they decided they want to have a child. Their battles in court lasted 12 years. Israel never granted them that right.

“You will never have a child,” the Israeli prison services director told Walid, according to Sana’.

The sixth geography

Walid began to identify his struggle to unite the span of time he spent in prison with the time in which his loved ones lived outside of it. He began to put words to this temporal reality as he approached the twentieth anniversary of his imprisonment. On the first day of his 21st year behind bars, he wrote to a friend:

I write to you from the Parallel Time. Here, where space is constant…we are in a time before the end of the Cold War. Before the first, second, and third Gulf Wars. Before Madrid and Oslo. Before the outbreak of the First and Second Intifadas…Before cell phones, modern communications systems, and the internet. We are a part of history, and history is obviously a state of past events that have come to an end. Except for us. For us, history is a continuous past that never ends.

Although he had coined the phrase “parallel time” in a previous text, the letter he wrote popularized the concept.

“Walid distinguishes between two times,” explains Abdul Rahim al-Shaikh. “The first is the linear, ‘social time’ lived by Palestinians in their ‘large prison,’ as Walid calls it, in the five geographical locations they occupy: Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza, ‘48 Palestine, and the diaspora.”

“The second is a parallel, ‘lingering-circular time’ lived by Palestinian prisoners in the ‘small prison,’ scattered across [what al-Shaikh calls] the ‘sixth geography’ — Israeli jails. The occupation authorities turn both prisons into an interchangeable laboratory for ‘life and death policies’ within a system of surveillance and control.”

The “life and death policies” that Walid Daqqah identifies as a means of controlling every detail of Palestinians’ existence are drawn from his own life experience and the life experiences of fellow prisoners. To Walid’s mind, the parallel time is one where prisoners build their own reality in order to resist the occupation’s control. Walid Daqqah’s thought, born out of practice, earned him the recognition of Palestinians as a landmark intellectual.

The birth of Walid Daqqah

In 2012, Israel released over 1,000 Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the release of the Israeli prisoner Gilad Shalit, who was held captive in Gaza since 2006. Many Palestinian families celebrated the homecoming of their loved ones. Wald Daqqah’s was not among them.

After losing the last ray of hope they had in reuniting and forming a family, Walid and Sana’ decided to “liberate” their unborn offspring, and began to try to conceive a child through Walid’s smuggled sperm.

By this time, Walid Daqqah had become a renowned name among Palestinian prisoners, alongside Marwan Barghouthi and Ahmad Sa’dat, with whom he met and engaged in discussions inside Israeli prisons. Yet Walid decided to extend his reach beyond the prison walls, to Palestine’s future generation, writing a children’s novel through the character of Jude, a young Palestinian boy who was conceived through his imprisoned father’s smuggled sperm.

In The Tale of the Oil’s Secret, Walid tells the story of how Jude is helped by a group of animals to reach an old enchanted olive tree, which gives him magic oil that makes him invisible, allowing him to break into prison to meet his father for the first time.

The Israeli Prison Service accused Daqqah of smuggling the novel out of prison and announced that punitive measures would be taken against him. Later, Israeli police banned the book launch that was to be held at a public hall in Walid’s hometown, Baqa al-Ghabiyyah, forcing the organizers to hold the event at his mother’s house.

But this wouldn’t be the last time Walid would suffer consequences for smuggling. In 2019, he smuggled his sperm outside of prison to his wife Sana’, and in February 2020 they welcomed their daughter Milad to the world.

Before Milad was born, the Shabak (Israeli intelligence services) had already opened an intelligence file on her. Sana’ and Walid had to fight the Israeli courts for their child to be recognized, and according to Sana’, the Shabak warned against Milad’s birth at one of the court sessions. During that time, Walid penned a letter written in the unborn Milad’s voice:

“I’m not scared of this government and its hubris. Not because I’m fearless, nor because I have faith that the preciousness of childhood will be recognized — as you will learn, this racist government has never had any concern for childhood — but simply because I stand above them, ethically speaking, as someone possessed of a right, the right of even the simplest of creatures, which is the right to live. They make death, and I’m the product of life. And here I ask you, what is insanity? Is it insanity that a child of my age speaks? Or that the Shabak has opened a file on her even before she is born?”

“Walid saw Milad for the first time after a year and a half,” Sana’ Salameh wrote. “We wrested the right for him to see her by fighting the courts. We went through a DNA test. We understood from the beginning that we had to battle this prerogative that they thought they had…the prerogative to ask: who is this girl? How come she is his daughter?”

When Milad finally met Walid, he had asked Sana’ not to carry her, and to let her come in walking. And she did. “But the one who was not standing on his legs, the one who was crying, was Walid,” Sana’ wrote. “All the prisoners cried.”

Walid’s prison comrades saw his daughter as their own. Perhaps it was because her story completed her father’s, just as her name completed his. Or perhaps it was that her story of resilience was theirs, that the little girl offered a window to the outside world for those ensnared in the parallel time. She embodied their connection to their people in the linear time plane, where life in the “big prison” was also built between the teeth of occupation.

The “liberated” offspring, just like the liberated novel or letter, represented a second birth for the denizens of the parallel time. Walid’s rebirth outside of it allowed him to exist in a world where neither myelofibrosis, medical neglect, nor solitary confinement could stop him.