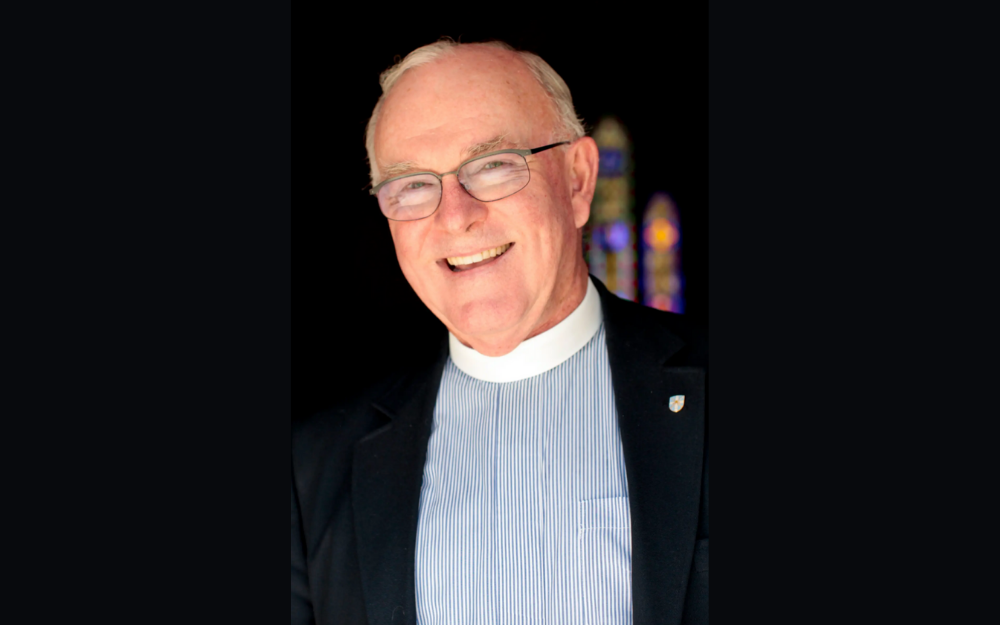

Yale University Episcopal chaplain Bruce Shipman says three sentences cost him his job.

In a short letter to the New York Times late August, Shipman responded to an op-ed by Deborah E. Lipstadt titled “Why Jews are Worried,” about rising anti-Semitism in Europe.

Here’s what he wrote:

Deborah E. Lipstadt makes far too little of the relationship between Israel’s policies in the West Bank and Gaza and growing anti-Semitism in Europe and beyond. The trend to which she alludes parallels the carnage in Gaza over the last five years, not to mention the perpetually stalled peace talks and the continuing occupation of the West Bank. As hope for a two-state solution fades and Palestinian casualties continue to mount, the best antidote to anti-Semitism would be for Israel’s patrons abroad to press the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for final-status resolution to the Palestinian question.

Within hours of the letter’s publication, Shipman says, people on and off campus began calling for his ouster. Two weeks later, he resigned. Why this happened—and what’s at stake—depends on who you ask.

Shipman has a long history of sympathy for the plight of Palestinians. As a teenager, he lived in Egypt while his father worked for World Health Organization and was there when Israel invaded during the 1956 Suez War. “Among my friends were Palestinian refugees and their children who were my age, so I heard their stories of dispossession and loss, people who had lost their homes and their farms and cut off from their land living in Jaffa and in the area which is now known as Israel,” he says.

He has visited Israel and the Palestinian territories more than a dozen times. This spring, he took a group of Yale students on a spring trip to Bethlehem and Jerusalem. “There is an apartheid situation there,” he says. “It is unpopular to say so, but it is the truth.” His letter, he explains, “suggested that in looking at the uptick in anti-Semitism in Europe and in the world, there is a correlation between the unresolved issues in Israel/Palestine, the recent war in Gaza and the terrible damage incurred by that war, the awful civilian casualties, and all of this I believe has contributed to an uptick in anti-Semitic violence,” he says. “That is what I said, and that is what I meant.”

Many people swiftly pounced. Yale pointed out that Shipman was not on staff but was rather employed by the Episcopal Church. Chabad at Yale, a Jewish student group, issued this statement: “Reverend Bruce Shipman’s justification of antisemitism by blaming it on Israeli policies in the West Bank and Gaza is frankly quite disturbing. His argument attempts to justify racism and hate of innocent people, in Israel and around the world.”

Religion columnist and Yale lecturer Mark Oppenheimer wrote that Shipman’s approach “gives license to all sorts of stereotyping, racism, and prejudice. . . . why wouldn’t one write, ‘The best antidote to stop-and-frisk policing would be for black men everywhere to press other black men to stop shooting each other’? Why wouldn’t one write—perhaps after a Muslim was beaten up by white-supremacist thugs—’The best antidote to Islamophobia would be for radical Islam’s patrons abroad to press ISIS and Al Qaeda to just cut it out’?”

David Bernstein wrote for the Washington Post, “Next on Rev. Shipman’s bucket list: blaming women who dress provocatively for rape, blaming blacks for racism because of high crime rates, and blaming gays for homophobia for being ‘flamboyant.’”

The official reason for Shipman’s resignation, according to the Episcopal Church at Yale, was not the letter but “dynamics between the Board of Governors and the Priest-in-Charge.” Ian Douglas, bishop of Connecticut and president of the board of governors for the Episcopal Church at Yale, emphasized this distinction to the Yale Daily News. “It’s not as glamorous a story to hear that Priest-in-Charge Bruce Shipman resigned because of institutional dynamics within the Episcopal Church at Yale and not the debates related to Israel and Palestine — but it’s the truth,” he said.

Shipman disagrees. “This story cannot be simply dismissed as the inner problems of the Episcopal Church at Yale. It was not,” he says. “It was this letter that set off the firestorm.”

For Shipman, the controversy raises a number of “troubling questions” about free speech on campus. In addition to the hate mail, Shipman says he has also received letters of support from people thanking him for taking a courageous stand for Palestinian rights. University chaplains, he adds, have a long history advocating unpopular cultural positions. William Sloane Coffin Jr., a chaplain at Yale during the 1960s, gained fame for practicing civil disobedience in protest of the U.S. war in Vietnam. Clergy today, he continues, needs to know what protections they do and don’t have when it comes to taking unpopular positions. “I think of abolitionism and the role the church played in that, I think of the civil rights movement, I think of the anti-war movement and the role the chaplains played in that, often incurring the wrath of big givers and donors of the university, but they were protected and they were respected,” he says. “That seems not to be the case now.”

As to what’s next for him, Shipman isn’t yet sure, but he doesn’t plan on remaining silent. “I think the truth must be brought out and it must be discussed on campus by people of goodwill without labeling anti-Semitic anyone who raises these questions,” he says. “Surely this debate should take place on the campuses of the leading universities across the country. If not there, where?”