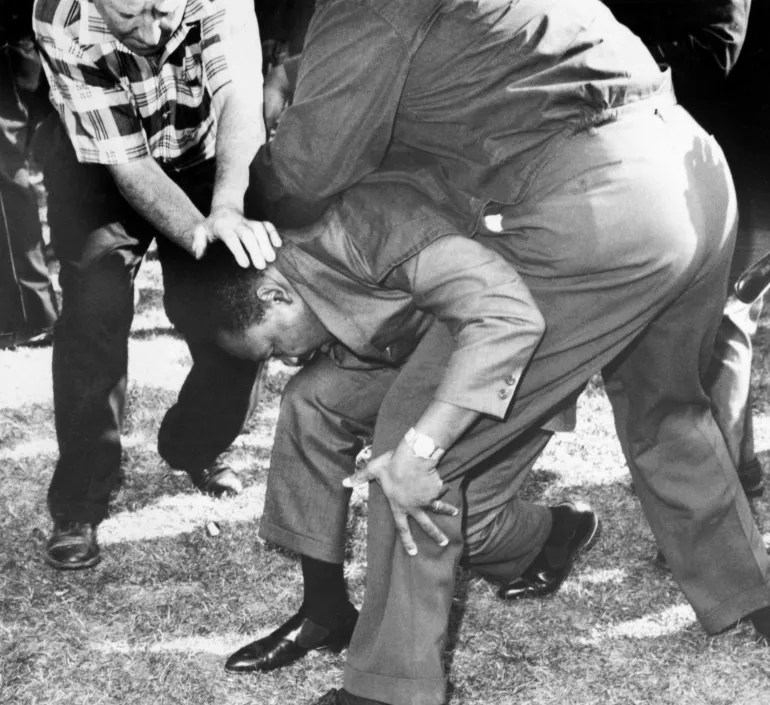

Dr Martin Luther King, Jr stands with fellow demonstrators as they are arrested for parading without a permit in Selma, Alabama in 1965 [Getty Images]

I’ll never forget my first organising training course in 2016. We walked through scenarios about arrests, communications, treating pepper spray, and supporting our comrades. And then the instructor, a young Black Chicagoan, slowed his speech, looked at all of us solemnly, and said, “Be prepared for anything. They will drag you. They will knock you unconscious. They will do whatever they can do to keep you from speaking out. They will literally kill you.”

At the time, during a critical period in the Movement for Black Lives, we were actively fighting against a system that had facilitated the killings of young Black Americans like Rekia Boyd and Quintonio LeGrier. As a collective, we were struggling to find justice for young Black people in Chicago who were facing the hyper-surveillance of the state, mass school closures, divestments in communities of colour and white supremacist violence.

As we commemorate Martin Luther King, Jr Day, I can’t help but think of moments like those, when I was concerned for my mortal safety in the name of political protest. Meanwhile, recent events prove that many Americans still do not understand why protests and riots are the domains of marginalised people rather than those in the leading class.

A crowd gathers inside Soldier Field Stadium during a ‘freedom rally’ billed as a ‘massive workshop in non-violence’ in Chicago in 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr, activist James Meredith and Congress of Racial Equality’s Floyd McKissick were among the speakers, followed by a march on City Hall [Getty Images]

The world watched on January 6 as hundreds of Trump loyalists descended upon the United States Capitol to stage a “self-coup”. The attempt was not to overthrow a sitting government but to keep President Donald Trump in power despite the election results confirming Joe Biden as the nation’s next president. What is particularly striking about this event has been the ways that white people continue to distance themselves from Trump loyalists and the systems so many of them seek to preserve.

The mob attack on the Capitol elucidated the grave disparities in policing and domestic militarism facing Black and white Americans, seeing as Capitol police failed to adequately protect the building. In that moment, white Americans who had actively worked to elect and support a white supremacist presidential administration were acting out their political fantasies on a grand stage. Moreover, they were showing how white Americans often escape the perils of the criminal justice system even when they are attempting to threaten domestic security and undermine US democracy on a global level.

In this moment, King would likely draw attention to the ways that Black protesters are frequently disproportionately attacked and punished for protest when compared to white Americans, even when those white Americans are engaging in anti-democratic mob violence. It is also in this moment that King would likely have encouraged and espoused a set of radical, Black liberationist politics in support of young Black Americans who have been risking their lives to ensure a freer and more just world for all of us.

King’s radical protest origins

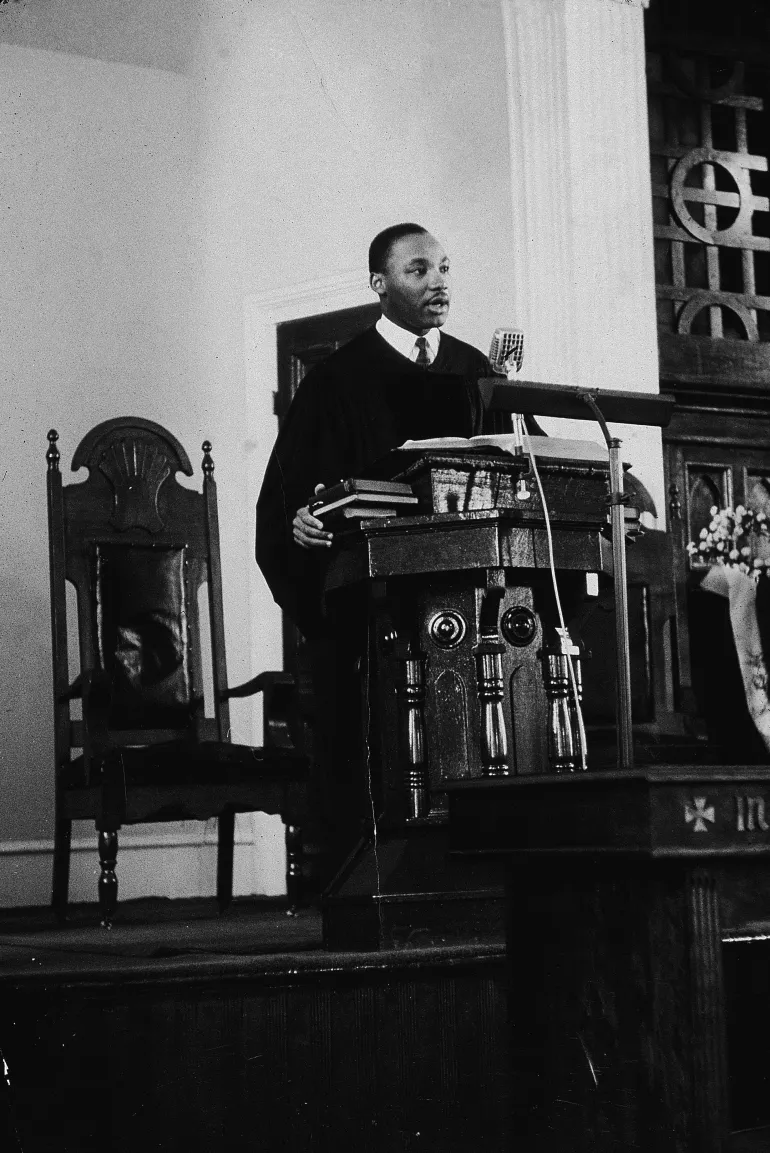

If there is one Black American hero whose radical legacy seems the most fraught and contested, it might be King. The civil rights leader, born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, was a minister’s son. An accomplished philosopher and thinker, he held a doctorate in theology by the time he was 26 years old. King became the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1954, the same year when the landmark desegregation case – Brown v Board of Education – was decided, changing the social and political landscape of the US educational system forever.

King speaks as pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama on March 20, 1956 [George Tames/New York Times/Getty Images]

It goes without saying that the political moment when King found himself coming of age was one that necessitated revolutionary change. Much like young Black people today, King’s radical ideals were born out of intense social unrest and violence. Over his short life, King’s political ideas and agendas evolved drastically, eventually moving away from integrationist politics to a politics rooted in Black liberation and freedom.

But, much of what we know about King’s life and legacy has been filtered through a revisionist lens meant to make white people more comfortable with their own complicity in systems of white supremacy and anti-Blackness. Thus, many white Americans have reframed King’s movement work and theorising as a way to water down the true aims of the man who became significantly radicalised, pushed by Black activists and organisers around him, before he was shot and killed on April 4, 1968.

King began to receive national attention for his involvement in helping strategise and execute the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which began on December 5, 1955, and ended more than a year later on December 20, 1956. It is estimated that the Montgomery City Bus Lines lost between 30,000 and 40,000 fares each day during the boycott. In retaliation for the success of the Montgomery Boycotts, King’s family home was bombed. It was also the Montgomery Bus Boycott that drew the initial surveillance of the FBI towards King’s efforts to radically change the US. King continued to face imminent threats of violence as he helped orchestrate mass protests across the country. During this time, King worked closely with communities and activists who further shaped his work in support of Black and poor people.

At the same time, King was a young, handsome man with impressive oratory skills and charisma. King’s sharp rise in fame also began to shape the notion that he was the de facto leader of what was becoming known as “the Civil Rights Movement.” This movement, while bolstered by King’s platform, had long been brewing in Black communities across the country. But it was King’s connections to church organisations and his ability to win over sympathetic white Americans with his message of morality that situated him at the head of the movement, at least in their eyes.

King urges calm from the porch of his home, which was bombed in retaliation for the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1956. With him, left to right, are: Fire Chief RL Lampley; Mayor WA Gayle (in uniform) and City Police Commissioner Clyde Sellers [Getty Images]

Radicalising Black Protest

Like the young Black Americans today who have been attacked, intimidated, and harassed by police during the protests of summer 2020, organisers in the 1960s were radicalising Black Protest. During this moment, young Black college students were desegregating lunch counters in silent sit-ins in the South. They were confronting Jim Crow laws and the antagonism of angry white people head-on. In April 1960, at a meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) – a civil rights organisation of which MLK was president – at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, activist and SCLC official Ella Baker invited young Black organisers, including the late Representative John Lewis, Marion Barry, and Diane Nash, to share their experiences. Baker had grown concerned that King might be falling out of touch with young Black organisers and their struggles against the state. These young freedom fighters became the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Tensions grew between King and the SNCC as the group espoused more radical politics and direct actions than the SCLC. Under the guidance of Baker, SNCC members risked their lives in “Freedom Rides” working to desegregate interstates. Lewis, among others, was beaten during the ride from Washington, DC, to New Orleans. Student activists were frequently arrested, stranded, and intimidated during the rides. The treatment of SNCC members in the 1960s resembles much of what we witnessed on the streets in 2020.

Plagued by these repeated confrontations with the state, King’s ethical commitments came under further challenge. As early as 1961, in the commentary, “After Desegregation – What?“, King reflected on the limits of desegregation and the potential risks to young Black Americans who would be faced with the ire of white American violence and racism even after the battles for desegregation had been won. King lamented the constricting conditions facing young Black Americans seeking higher education at the time. He was aware that, for young Black people in 1961, integrating interstates, colleges and universities, and other public spaces was almost certainly a confrontation with the vestiges of the crumbling Jim Crow system riddled with social mores and norms meant to persecute Black people.

A crowd of students at Woodlawn High School in Birmingham, Alabama, fly the Confederate flag in opposition to the start of the Birmingham Campaign, a desegregation movement, in May 1963. The movement was organised by the SCLC’s Martin Luther King, Jr and Fred Shuttlesworth, among others [Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images]

Though King was struggling with the ongoing violence facing young organisers in the SNCC, he still believed that white racism and the reliance on anti-Black tropes in assessing the humanity of Black people would eventually go away. King wrote, “As the color differential fades, so will the racial point of view. Less and less will it be possible to speak with accuracy of Negro newspapers, Negro churches or the Negro vote. More and more economic, social, and professional status will be more decisive in determining a man’s orientation than the color of his skin.”

These sentiments foreshadowed King’s famed “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963. It was after this grand speech that the FBI shifted to covert surveillance of King and his comrades. Following the speech, then-FBI Director William Sullivan famously wrote of King, “We must mark him now, if we have not done so before, as the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation from the standpoint of communism, the Negro and national security.” That year, the FBI met to plan ways to “neutralise King” as a political leader. The increased surveillance of King’s organising and direct actions contributed to tensions between the movement and the federal government.

The preoccupation with King’s personal dealings and companionships culminated in an “intensive investigation” meant to cast aspersions on King’s character. These wiretaps remained active until April 1965 at King’s home and June 1966 at the SCLC offices. The unlawful and baseless wiretapping of King’s comrades and family is just one of the ways the US government actively worked to discredit the growing interracial movement of supporters who remained committed to ending segregation. These actions also contributed to King’s growing distrust of the government and his ever-radicalising ideas on justice and liberation.

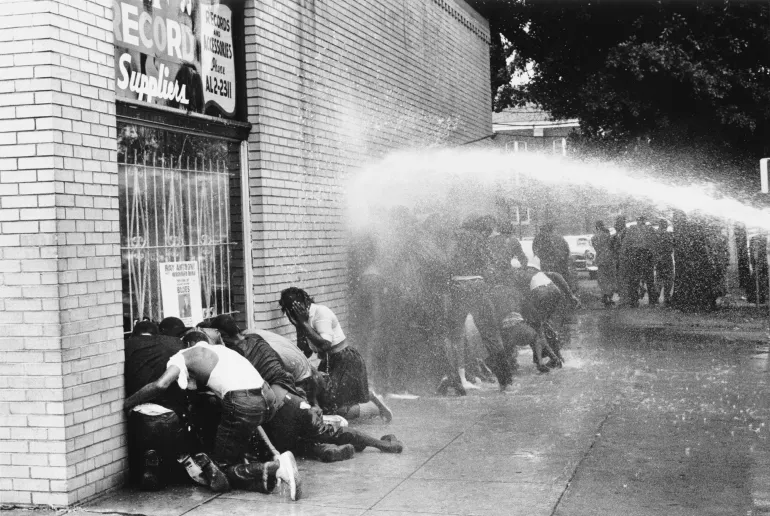

Water cannon is used on young Black Americans during a protest against segregation organised by King and Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, in Birmingham, Alabama in May 1963 [Frank Rockstroh/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images]

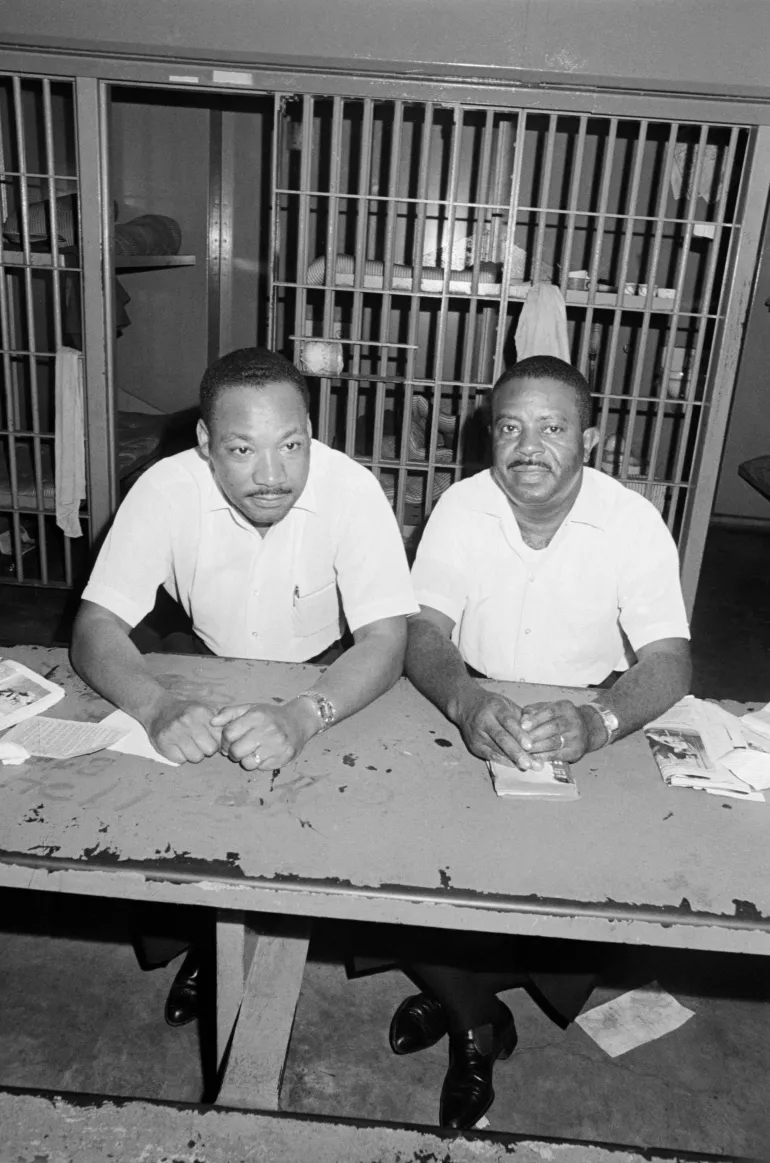

The aggression of white supremacists and the growing violence of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) around the country increased in response to the growing coalitions of Black activists and organisers securing wins for Black Americans. In 1963, King was arrested and held in a jail in Birmingham for protesting segregation. There, he penned the “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in response to white clergymen who had criticised his ongoing confrontations with the state. His blistering response was one of the many redactives he crafted to white liberals as his political career grew more radical.

In the letter, King wrote, “I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice.” He went on to explain that white moderates were those who “set the timetable for another man’s freedom.”

Arrested after integration attempts in Saint Augustine restaurants, Martin Luther King sits with Reverend Ralph Abernathy in the St John’s County Jail in Saint Augustine, Florida in 1964 [Getty Images]

For King, the lack of consistent support from white clergy and other advocates of the movement was just as harmful as the outright rebuke of KKK members.

Then, in September 1963, four little girls were killed by white supremacist bombers at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. The church had been a meeting place for King and local organisers. The bombings, set to strike fear into Black Americans and warn them away from white neighbourhoods, earned the city the nickname “Bombingham”. It was indicative of the ongoing violence and racial pogroms erupting nationwide.

This tragic event was devastating for King. Like many young Black Americans today, witnessing this macabre violence against Black people triggered in him a deeper commitment to challenging the status quo.

King looks through the window of a police car moments after he was arrested at the Birmingham Airport in 1967; King and three others received five-day jail terms for violating a court order by staging a demonstration in Birmingham on Easter Sunday in 1963. They appealed the case to the US Supreme Court but lost. King sent word from his jail cell that he was confined to bed with a virus infection and under the care of a doctor [Getty Images]

Bloody Sunday, MLK and Black Protest

On March 7, 1965, the day now known as “Bloody Sunday”, nearly 600 peaceful protesters set out on a 54-mile journey from Selma to Montgomery only to be met on the Edmund Pettus Bridge by police officers with billy clubs, whips and tear gas. John Lewis, who was only 25 years old at the time, was among those brutally beaten on the bridge that day, his skull cracked by state troopers using a billy club. The macabre violence was televised to millions of Americans during primetime. For many white Americans who had been largely insulated from the racial violence facing Black Americans in the US, this broadcast was their first direct exposure to the Civil Rights Movement.

Following this violence, from March 21 to March 25, 1965, King led the Freedom Marches from Selma to Montgomery. King’s targeted direct action campaigns in Selma put pressure on then-President Lyndon B Johnson to push for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, sweeping legislation meant to end the era of literacy tests, poll taxes, and other barriers Black Americans faced to voting in the US.

In a major blow to King’s legacy and work, the US Supreme Court invalidated key parts of the Voting Rights Act in 2013.

Towards the end of his life, King turned his focus to the Poor People’s Campaign, an effort to unify Americans behind issues like equitable pay, unemployment insurance and a fair minimum wage. He never got to see the culminating events of the Campaign as he was killed before the project was completed.

King was a critical force in bringing the anti-Black, racist struggles facing Black Americans to the communities, living rooms, and dinner tables of white Americans who had long had the privilege of overlooking and denying its existence. He did this while sacrificing his own safety and the safety of his family.

King is struck on the head by a rock thrown by a group of white men; he regained his feet and led a group of marchers demonstrating against housing discrimination through an all-white district in Chicago on August 5, 1966. Hundreds of jeering people lined the march route, showering the marchers with stones, bottles and firecrackers [Getty Images]

While King believed that the fundamental tactics of mass mobilisation and movement making for racial progress should focus on a non-violent course of action, he also challenged activists and organisers to shift their focus to systemic and institutional barriers to progress for Black Americans. In 1968, just before he was killed, King said, “A riot is the language of the unheard.” What we know of his legacy is that, while he did not support violent protest tactics, he believed that the only way to prevent rioting was to address the underlying concerns of those in the minority. King was clear that white people would not lead the revolution. Rather, it was always the voices of young, Black, and poor people that were most heard during times of great anguish and upheaval.

Suffice it to say, King was not confident that powerful white people would work toward justice for all. In a speech about his Poor People’s campaign, he said, “I don’t have any faith in the whites in power responding in the right way … they’ll treat us like they did our Japanese brothers and sisters in World War II. They’ll throw us into concentration camps. The Wallaces and the Birchites will take over. The sick people and the fascists will be strengthened. They’ll cordon off the ghetto and issue passes for us to get in and out.” Exasperated by the continued violence and economic disparity facing Black people, King had become disillusioned with the capacity for white leadership to be responsive to the political concerns of Black Americans. Most importantly, he had come to the realisation that white Americans would frequently choose their own safety, liberty, and economic stability over the collective good of others.

Towards the end of his life, King’s ideas and work had made him increasingly unpopular. In 1966, 63 percent of Americans had an unfavourable view of King, up from 37 percent in 1963, according to Gallup. The precipitous change in public opinion about King in the 60s illustrates how his public politics and commitments became less palatable for white Americans not fully committed to the liberation of poor and Black people. Yet, even as the public slowly turned away from King and his work, he continued to promote notions of class equality and Black humanity despite the risks to his own life and the lives of his family and comrades.

Members of a right-wing organisation picket outside Cobo Hall in Detroit, Michigan in 1965, demonstrating against King who addressed a dinner inside [Getty Images]

We must acknowledge King’s radical legacy

It is the same fight we continue today. Young Black Americans have been in the streets fighting for their lives and for the safety of their communities. The protests after Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were killed by police have been described as the largest global mass protests in history. All of this in the midst of a global pandemic, where Black Americans are at greater risk of dying due to COVID-19 than any other group.

In general, Black Americans are at greater exposure for environmental risks that have only worsened under the Trump administration. The global crisis has only highlighted the grave disparities in health and safety across racial groups. Even before the pandemic, Black women were at the highest risk of death due to childbirth complications. Black children face higher rates of death from complications with asthma. Meanwhile, some Trump supporters have manifested their denial of his recent loss by appropriating protest and engaging in acts of violence as a form of national pacification.

We must acknowledge King’s radical legacy in light of recent events. Not only that, we must consider how his evolving politics provide insight into the ways that young Black Americans today continue to be politicised and radicalised by the anti-Black world around them.

King’s legacy teaches us that political protest, and his fight for economic justice for all people, is a tool to challenge the status quo rather than assimilate into it. His work shows that, as the conditions of state-sanctioned persecution and inequality change, we too must allow ourselves to be changed. And, when the world calls us to respond to oppression and repression, we must always concern ourselves with those least protected, least defended, and most vulnerable to the violence of the state.

We should be suspicious of the watered-down, colourblind notions of King’s politics that too often dominate mainstream narratives. And, as white Americans continue to commodify and appropriate King’s legacy for performative acts like the “MLK Day of Service” and other public displays, we must remember that this is the same MLK the FBI tried to convince to kill himself – only to tweet in his support decades later.

King arrives at the FBI on December 1, 1964, to speak with director J Edgar Hoover, who had called King ‘the most notorious liar in the country’ at a recent news conference [Getty Images]

If King were here today, he would likely express both disappointment and disgust for Trump loyalists whose anti-democratic commitments leave this nation in a consistent state of uncertainty and turbulence. And, unlike the violent mob last Wednesday, King would be speaking as a Black American who has been physically threatened, surveilled, and harassed by state-sanctioned eyes. Through his life and legacy, it is clear that Black Protest has always been criminalised, and deemed riotous. This is true even though many white Americans consistently support the violent, anti-Black status quo.

Like so many of us who are committed to racial justice and accountability to those least among us, King’s legacy is a balm in a moment such as this. King would have been fighting with and alongside young Black Americans following the deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and so many others. And, he would have seen the January 6 attempted coup as a toothless white supremacist attempt to grasp at the reigns of power in the US despite the immense damage this administration has already done.