Called the ‘Holy City of Morocco’, Fez is, above all, noted for its Qarawiyin mosque – the symbol of the country’s intellectual life and its most prestigious historic site. For more than eleven hundred years it has been the haven for Islamic scholars and religious officials. Enhancing this aura of learning are medersas (Islamic schools) which dot the city and hug the Qarawiyin in a loving embrace.

Inspired by the schools in Baghdad, they were, in the main, built by the Marinid sultans, during the 14th century. As Islamic colleges with lodgings for students who came to study, besides religion, the Arabic language, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine, they were unequaled, in their time, as places of learning.

The majority of these schools were built in the same fashion. Each medersa had two levels and a central courtyard, incorporating a fountain, used in ritual ablutions. A colonnade or gallery surrounded the courtyard, which is edged by a large room, serving both as a lecture hall and a place for prayer. The student rooms or cells were mostly located on the second level but, in a few of the schools, there were a number on the first level.

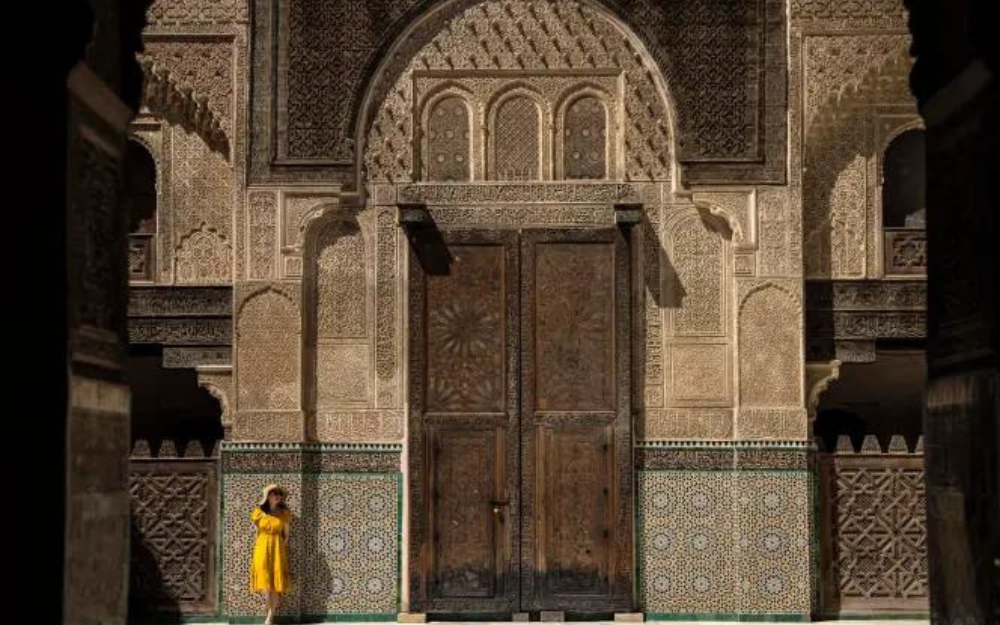

The medersas were all exquisite works of art, decorated with carved wood, geometric designs and floral motifs and lace-like plasterwork. Each one is a creation of perfect handiwork by master craftsmen.

Yet, in spite of the ostentatious splendour of the buildings, the students, living two in each cell-like room, led a frugal life. In these usually damp and dark rooms, they prepared their meals, slept and studied. Their lodgings, bread and drinking water were supplied free, but they had to buy their own books and most of their food. Hence, many were compelled to work part-time as lecturers in mosques or as servants in the homes of the affluent.

The mother of all of Fez’s medersas is Bou Inania, built in the mid-14th century by Sultan Abu Inan, the first ruler of the Marinid Dynasty. Incorporating direct importation of 14th century Andalusian building techniques, the school is different than the other medersas in that it had an imposing minaret and served both as a mosque and a school.

Its doorways, columns, courtyard and hall are all extravagantly decorated with dark cedar, exquisitely carved; floral and geometrical patterns; delicate lace-like stucco, toughened with egg white; marble floors; and ceramic-tiled lower walls covered in Arabic script with academic messages – one reading, ‘This is a place of learning’. The whole inside is a stunning combination of decorative artwork. However, like the other medersas, its student cells are barren and forlorn.

It is said that Sultan Abu Inan built the school to rival the city’s grand Qarawiyin mosque and its cost almost broke the treasury. Because of the great expense, a story is told that the Sultan threw away the account books into the river saying, “A thing of beauty is beyond reckoning.”

Opposite Medersa Bou Inania, but connected to this school, is a medieval water clock, consisting of 13 windows and platforms – seven of which still retain their brass bowls. High over them on a carved lintel of cedar is a decaying row of 13 windows. Forgotten for centuries, the clock is being renovated and hopefully, in the future, experts will be able to have it working again.

The grandest, most elaborate, and beautiful of all the Marinid monuments, Bou Inania comes close to perfection in every aspect of its construction. It is the one historic site not to be missed by travellers, in fact, it is the only structure still in religious use which non-Muslims can enter. Almost every first-time tourist in Fez takes a photo of Bou Inania’s green-tiled minaret through the Bou Jeloud Gate – the most utilized point of entry into the old walled medieval town into which no auto is allowed to enter.

The Marinid Sultan Abu Said built Madersa El Attarine next door to the Qarawiyin mosque in the 14th century. He built it on the edge of the spice souk – hence, its name, Attarine (from the Arabic ‘atir (spices). In fame, it comes second to Bou Inania. Some claim it is more beautiful and delicate, and more perfect than that medersa.

It is an incredible structure, with a profusion of fine pattering in blue and white tile, wood and stucco. Verses from the Koran are incised in continuous friezes and are breath-taking in their intricacy. Even though some renovation has been made, basically the school is in an excellent state of preservation. Without question, its graceful proportions, elegant geometrical carved-cedar ornamentation and distinctive brass doors make it a living medieval work of art.

Medersa Shrij is the third finest of the Fez medersas. Erected in the 14th century, it was named after its beautiful ablution pool (from the Arabic saharaj – pool). Noted for its rich carvings and its aura of calmness and tranquility, it is worth a visit. However, if one has visited Bou Inania and El Attarine, this school does not have anything really new to offer.

Medersa es Seffarine, constructed in the 13th century is the oldest medersa built in Fez. Unlike the other schools, it is built like a traditional Fasi (Fez) home and gets its name from Seffarine square (from the Arabic afar – brass) where craftsmen hammer metal into huge urns sand pots. The medersa still houses some students and is only worth a visit if one has time to spare.

Edging the medersa on the square stands a marble fountain, decorated with a carved fleurs-de-lis and one side of the Qarawiyin mosque’s library – one of the most important libraries in the Arab world.

The newest of these medieval schools is Medersa El Cherratin, built in the 17th century by the Alaouite Sultan, Moulay el-Rachid, founder of the present Moroccan dynasty. Noted for its double bronze-faced doors and fine doorknockers, it is much less ornate than the medersas built by the Marinids. However, as a school it is much more functional. Designed to hold more than 200 students, it contrasts vividly with the intricate craftsmanship of the medersas erected during the earlier Marinid era.

Rarely visited by travellers are the few remaining less important schools like Medersa Misbahiya, now under renovation. Built in the 14th century by Sultan Abu Hassan, it is noted for the lavish use of marble in its construction.

For visitors seeking historical architectural gems, these schools have few equals as relics from the medieval era. Yesterday, they drew students from the whole Islamic lands; today they draw tourists from the four corners of the world.

By Habeeb Salloum/Arab America Contributing Writer