Atef Mohamed standing near where he intends to put the Adhan speaker. [Haidee Chu/THE CITY]

It was just past 4:33 p.m on Wednesday when the unfiltered sunlight overhead cast a shadow of Sheikh Atef Mohamed that matched his height — a telltale sign that it’s time for the third prayer of the day.

“Allahu Akbar, Allahu Akbar,” a summoning tune soon resonated throughout the prayer rooms of Masjid El-Ber, which opened its doors in 1980 in what’s said to be Astoria’s first ever mosque.

On the bustling street, though, the ebb and flow of the rhythmic call to prayer — seeping out through an open window — was dampened by the sounds of traffic and the overhead train track down the block.

“We’re going to have the speaker” outside, Mohamed, the 70-year-old president of the mosque, said as he pointed to a corner of its red-brick exterior wall. “We’re going to put it right here.”

Days after three other Astoria mosques — Masjid Dar al-Dawah, Masjid al-Iman and Astoria Islamic Center — received the neighborhood’s first-ever permits to broadcast calls to prayer from the street, just in time for Ramadan, Masjid El-Ber submitted its own application to do so.

These calls to prayer — or Adhan, in Arabic — typically last between three to five minutes and are called five times a day, with the first one starting before the sun rises. The Astoria permits, Abdelhamid said, begin with the second prayer of the day, at some time between noon and 1 p.m.

Mosques in other parts of the city, including one that sits along a part of the Brooklyn-Queens border, have in the past been subjects of noise complaints, about the call to prayer waking or disturbing nearby residents — along with sometimes vicious or threatening comments about Muslims.

In Astoria, by contrast, the Adhans being played outside of the mosques has been greeted with enthusiasm by the neighborhood’s Muslim community, and with little to no pushback or news coverage outside of it so far.

Rana Abdelhamid, who submitted applications on behalf of all four mosques to the local 114th Precinct — the last step of a process she said began in January — noted that the permits will last until the end of Ramadan, but that she hopes and expects they will become permanent after that.

Ramadan, a holy month of daytime fasting, introspection and renewal for Muslims, comes according to the Islamic lunar calendar so that it rotates between seasons over time. The five daily prayers become especially important during this time, Mohamed said, as followers focus on repentance and growing closer to their faith.

A sign outside of the Masjid El-Ber mosque. [Haidee Chu/THE CITY]

“I likened it to church bells, and that for Muslims, when we pray five times a day, it’s really important for us to be able to hear the call to prayer,” Abdelhamid said on Tuesday.

“What they told us is that if everything goes well during Ramadan, and if there’s no challenges or pushback from the community, then they should go past Ramadan,” the founder and executive director of Malikah, an organization “advocating against gender and hate based violence,” continued.

“So Inshallah, nothing bad happens,” she said, using the Arabic phrase for “God willing.”

The sonorous Adhan continued on that Wednesday afternoon as one onlooker reacted with confusion when he strolled past the mosque, looking all around as if to trace the origins of the sound.

Others, like Mr. Rahman, who declined to give THE CITY his first name, responded with eager anticipation to the familiar words.

“As-Salaam-Alaikum,” Rahman stopped his steps to greet Mohamed and to inquire about the group prayer upon hearing the Adhan. “What time is the Iqama?” He added, referring to the second, shorter call to prayer meant to remind people already in the mosque to get in formation.

“Five, Inshallah,” Mohamed responded. It was now about 4:45 p.m.

Rahman, who is a long-time Astoria resident, said Adhan calls on the streets are ubiquitous in his native Bangladesh. Here in the U.S., he said, there should be “at least [a] little sound so people can hear it.”

“Inshallah, we’re gonna put a speaker here, Inshallah, as soon as we get a permit,” Mohamed chimed in.

“Oh that’s good!” Rahman responded in delight. “So other people can hear it, you know. So Muslims — they can be attracted, they can come to pray, Inshallah.”

Today, nearly 4,000 immigrants from Bangladesh, another 2,000 from Egypt and more than 1,000 from Morocco live in the neighborhood, according to the 2021 American Community Survey estimates, with many of them on the blocks by the mosques.

But the neighborhood did not always look like this, Mohamed said. A Muslim enclave was only beginning to emerge in this majority Greek and Italian corner of Queens when he arrived from Egypt in 1985.

“When you come from a country like Egypt, and you are coming from a religious family, and you pray, and then you come and see yourself here — and there is no mosque, there is no Adhan, there’s nothing to remind you with the prayer … So you will feel kind of like ‘where am I?’” Mohamed said.

‘This Is Our Identity’

As the clock approached 5 p.m. on Wednesday, the stream of people trickling through the stainless steel doors that creaked open and closed at Masjid El-Ber reflected this diversity of the faith: Egyptians, Bangladeshis, Moroccans, Palestinians, along with the occasional Bosnian and Albanian.

The entrance to the Masjid El-Ber mosque leading to the men’s prayer room. [Haidee Chu/THE CITY]

But this display of faith has come with its challenges at times. Abdelhamid, 29, recalled growing up in Astoria in the 2000s, amid “racial profiling” of Muslims, so that many people tried to stay under the radar or felt that they had no choice but to do so.

“A lot of people shed their identities, changed their names, took off their hijab,” said Abdelhamid, who visits and prays regularly at many of these Astoria mosques. “Now, we’re unapologetically Muslim. This is our block, this is our mosque, this is our identity, and we are going to worship in a way that is authentically ourselves.”

Masjid El-Ber called out its first Adhan in 1996, Mohamed recalled, which at the time meant a caller loudly performing the summon in front of the mosque without amplification. At some point after that, they installed a speaker inside the mosque to amplify the call.

A qualified Adhan caller, Mohamed explained, must possess deep knowledge of the religion, familiarity with the vocal nuances of the Adhan call, and the gift of a palatable voice.

“If you call the Adhan in a good way, you make people happy, it’s relaxed,” 56-year-old Ahmed Amechtak, who had been the afternoon’s prayer caller, chimed in. “But if you don’t have a good voice, it’s not your place.”

“And you see, my voice is not clear like his,” Mohamed added of Ahmed, who was standing beside him. “So it’s different.”

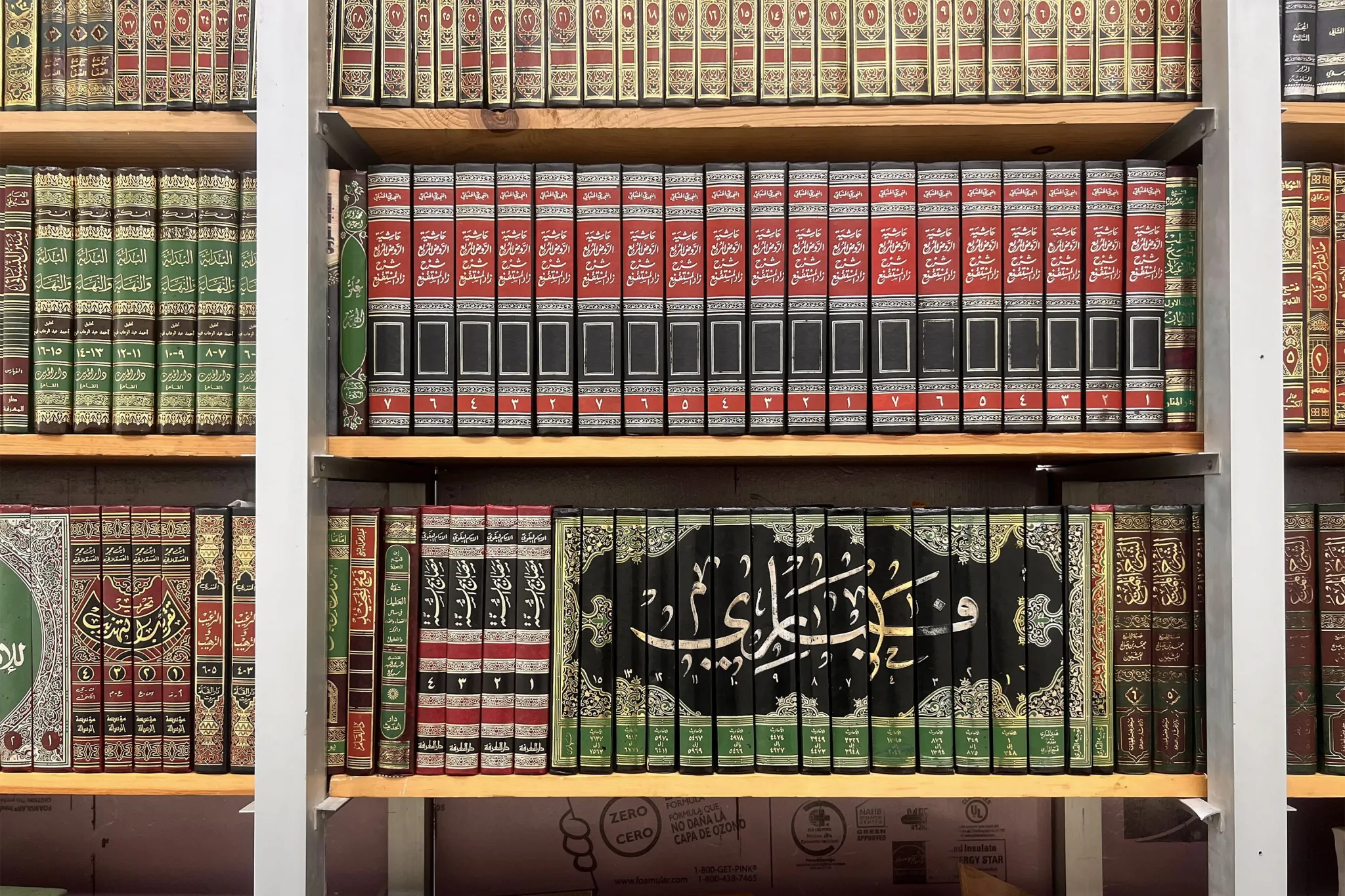

Books line the walls of the women’s prayer room at the Masjid El-Ber mosque. [Haidee Chu/THE CITY]

The afternoon prayer soon commenced with the signal of the Iqama. Followers in the men’s prayer room organized themselves neatly into parallel rows of about 10 facing the Imam, who led a congregation of about 50 men through about 15 minutes of prayers, bows and prostrations.

“As-Salaam-Alaikum,” 48-year-old Karima Jaser said as she arrived belatedly at the women’s praying room, where she was the only follower in attendance. Carefully, she rolled out her royal-blue mat and followed through with the prayer.

“Yesterday was — oh my God,” said Jaser after the prayer as she described the feeling of hearing the Adhan being played outside by one of the mosques that had already obtained a permit.

Her eyes swelled with joy, as she spoke about how hearing the calls outside of the mosque reminded her of Palestine.

“The feelings? The chills? Oh my God!”

‘We’re All Connected’

As the mosque began to clear out following the afternoon prayer, Mohamed recalled his first Ramadan in the U.S., in August of 1986. “It was the longest day ever,” he said, recalling the heat, humidity and his fast over 18 hours. “Working in ice cream,” he said, did not help the time pass more quickly.

“I came here in November and it was the easiest Ramadan I’ve ever had,” countered Amechtak, who immigrated from Morocco in 1999. “We don’t have that short day in my country.”

But that first Ramadan in Astoria felt different for other reasons too, Amechtak added.

“In my country, there’s only my people — culture is the same thing. But here, culture is different. We got other Muslims,” he said, noting as an example the different foods that people from different countries eat to break their fasts.

The communal feeling of being at the mosque, Mohamed noted, was a great compensation for immigrants like himself missing their home countries.

“We made our own brothers and sisters here,” he said as he stood next to Amechtak. “Actually we don’t care about the culture as much as the religion. We’re all connected.”

“He prays next to me the same way that I pray,” Amechtak added.

Mehfuzer Rahman, Atef Mohamed, Ahmed Amechtak (From left to right). [Haidee Chu/THE CITY]

Mehfuzer Rahman walked into the mosque shortly after. The 68-year-old, Mohamed said, takes care of nearly everything that goes on in the mosque.

That includes waking up before dawn to make the mosque’s first Adhan — sometimes as early as 3 a.m.

“He calls the Adhan with a Bangladeshi accent,” said Mohamed, looking to Rahman. “And this is a Moroccan” accent, he continued, pointing to Amechtak. “And my Egyptian,” he concluded. “So it all comes out.”