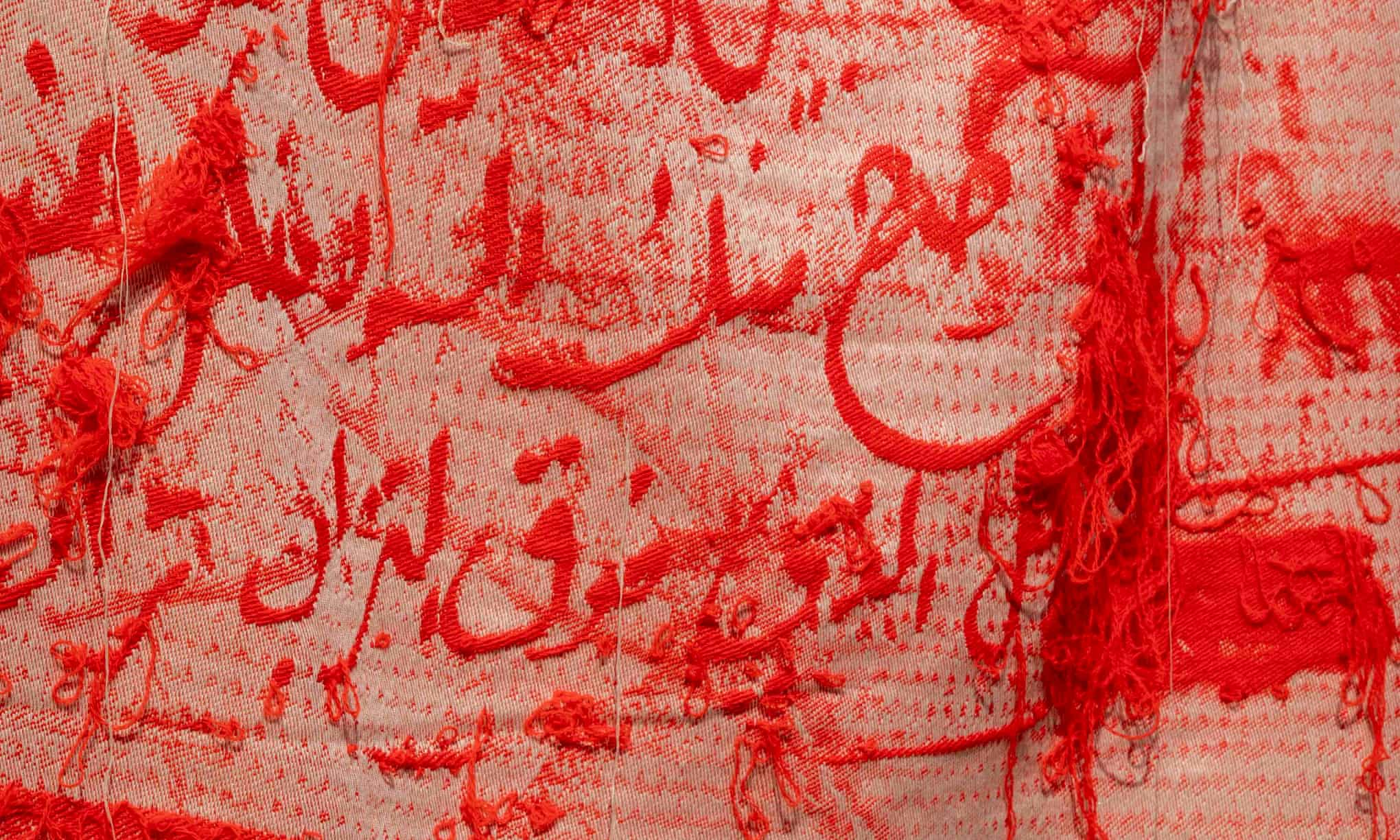

Hopes and fears, flickering through memory … a detail of Hadeyeh Badri’s artwork. Photograph: Peter Kelleher/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Words have had outsize importance in Muslim culture since the beginning. The Qur’an, which literally means “recitation”, was of course revered as the word of God. But, crucially, images of human beings and animals were disapproved of because they could distract people from prayer; as a result, artists poured all their creativity and imagination into calligraphy. Facing the same restriction, craftsmen and architects created dazzling geometric forms into which words were often incorporated. The discipline imposed by not being able to depict living things gave rise to some of the most beguiling decoration on the planet.

This bias towards the word and against the portrait still lingers. So it’s no surprise that an exhibition by nominees of the V&A’s Jameel prize, which rewards artists inspired by Islamic tradition, has an intricate feel, all pattern and texture. The artworks are often documents, with text transferred on to paper bags, rugs or T-shirts. For visitors who can’t read Arabic script, writing will merge into ornament: dots and curlicues, strokes and ligatures dancing on the fabric or page. But this isn’t always a barrier – often the word itself is not the focus, rather its form and what it represents.

That’s the case, for example, in Lahore-based artist Bushra Waqas Khan’s work. Her source material is affidavit paper, printed sheets used for official documents in Pakistan, covered in the kind of decoration you find on passport pages or banknotes. She cuts out the various headings and motifs and reassembles them into stiff-looking Victorian ballgowns about a foot tall. The word Pakistan, repeated over and over, becomes an elaborate hem. Colonialism, nationalism and officialdom are all being subtly lampooned here, as is the idea of women as property: affidavit paper is often used as proof of ownership.

In Hadeyeh Badri’s textiles, hand-woven phrases in shimmering red fade in and out of view, sometimes clearly defined, sometimes half-obliterated. They represent fragments of letters from her late aunt Shahnaz, and are Badri’s reinterpretation of an ancient trope in Arabic poetry known as al-waqaf ala al-atlal, or “standing by the ruins”. In it, the protagonist stops beside the traces of a campsite or settlement where he met his beloved years ago and imagines her there again. In Badri’s work, the words themselves are the ruins, and gazing on them conjures Shahnaz, her hopes and fears flickering through layers of memory.

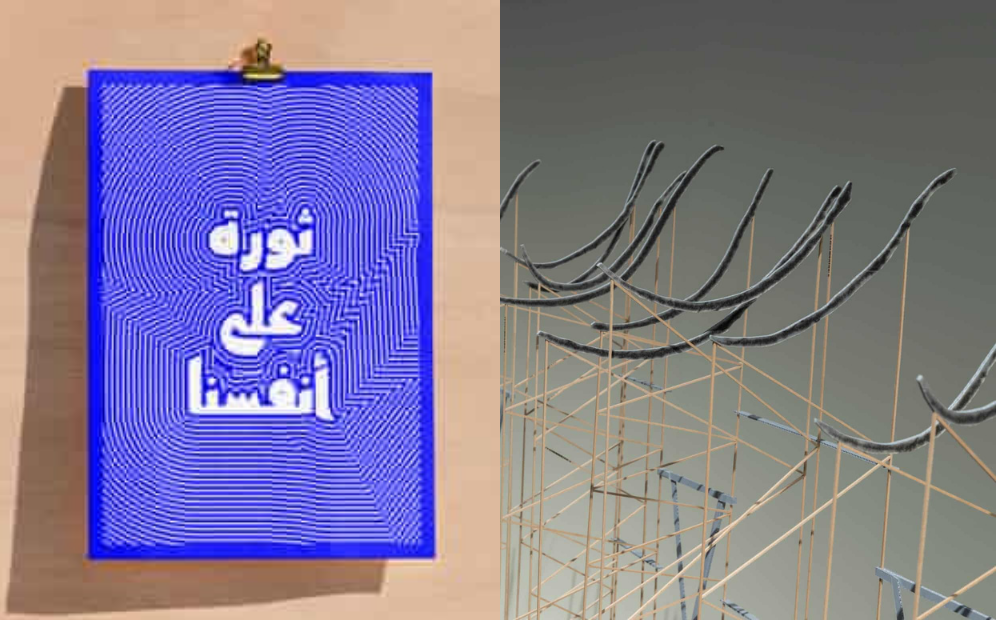

Farah Fayyad’s Kufur typeface. Photograph: Farah Fayyad.

A hundred cresting waves … Golnar Adili’s Ye Harvest from the Eleven-Page Letter. Photograph: Peter Kelleher/Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Ancient themes are also brought up to date in Farah Fayyad’s graphic designs. She has adapted Kufic, the extraordinary style of calligraphy in which the earliest Qu’rans were written, as a typeface for the digital age. Kufic was already ahead of its time, strangely fat and elongated, like a 70s sci-fi director’s idea of how aliens might write. Fayyad’s interpretation, called Kufur, is friendlier, more bulbous, but she puts it to serious use: cryptic slogans such as “I wish we could run like the river” and “It will not defeat me” evoke the spirit of 1968. In 2019, Fayyad found herself in the middle of street protests in Beirut, printing T-shirts with revolutionary statements on them for people to take away and wear.

Against this obsession with the written word, Saudi artist Ajlan Gharem’s work could seem out of place. His installation Paradise Has Many Gates is a large chain-linked metal cage that, with a rudimentary dome and minaret, takes on the familiar shape of a mosque. It’s represented in the exhibition by beautifully stark photography and a video of it in the desert outside Riyadh. But while it eschews text, it remains abstract, line and volume rather than flesh and blood. Given the context – Saudi Arabia, where free expression is highly restricted – should we assume it’s deliberately inoffensive? A “mosque” into which you can read any number of things, including the artist’s own religious devotion? Gharem may be treading a careful line, but it’s clear he views this artwork as subversive. “A few years ago, it would have been too dangerous for me to do this kind of work, but things have changed,” he told the Art Newspaper. In a video made for the exhibition, he says: “The mosque in my work is not a reflection of religion or faith, but rather the particular form of religiosity from which came extremism and fanaticism”. He adds, a little ambiguously, “It’s that ideology that is the prisoner, not the religion.”

Treading a careful line … Paradise Has Many Gates by Ajlan Gharem. Photograph: Ajlan Gharem

The Jameel prize jurors were sufficiently intrigued to choose Gharem as this year’s winner. But in doing so, they may have overlooked standout work by Iranian American Golnar Adili, whose Ye Harvest from the Eleven-Page Letter marries pure form, memory and loss in a deeply affecting way. Ye is the last letter of the Arabic (and Persian) alphabet. When it appears at the end of a word, it inscribes a wide curve. Adili, who spent much of her early life separated from her late father, pored over a long handwritten message he once sent to “a lover”, identifying every single example of this word-final ye. She treated them like objects of reverence, stripping them out of the text and enlarging them so they look like a hundred cresting waves. The culmination of the project sees them transformed into sculptures, elevated on to spindly wooden stands, stiff black worms echoing one another in a long line. “It was as if I wanted to bring back my father through his handwriting, but also to just kind of make this emotional graph of him.” Adili manages to generate profound emotion from meticulousness and abstraction in a way Muslim artists through the ages would undoubtedly recognise.