Photos by Mouna Photography

Madison artist Faisal Abdu’Allah’s “Dark Matter” opened Friday at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, 227 State St., Madison. The exhibition runs through April 2.

On an exchange visit to the United States as a teenager, Londoner Paul Anthony Duffus “was impressed with how Islam was a tool revolutionizing the lives of Black Americans,” he said in a telephone interview after the opening Friday of his exhibition “Dark Matter” at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. He familiarized himself with Malcom X’s journey of self-discovery and others who had similar stories. He felt inspired to take his own.

“Islam addressed who you are,” he said. “I realized I did not have a name that aligned with my identity,” he said of the Scottish name he was given at birth. “That’s when the ball started to roll.”

At 19, he returned to an England where a “huge awareness was growing, and men and women were finding a new place and identity.” Duffus began learning about Islam. He soon made his Shehadeh, the Muslim declaration of faith that there is one God and that Muhammad is his prophet. He adopted a name for himself, chosen by a sheik in South London, “that better suited” him, “Faisal Abdu’Allah.” The Arabic name both signals back to his ancestral roots on the African continent and to the Islamic faith. “Faisal means ‘the judge,'” he explained.

In the 30 years since, Islam has impacted his life and his art. “The discipline, changing the sleeping habit to get up early for prayer, praying five times a day, eating differently, changing my social circles, reading Arabic,” he listed. “It did not introduce different principles. It calls on us to be generous, kind, good,” as did the lessons he learned from his father, a Christian minister.

Today Abdu’Allah is Professor of Printmaking and Associate Dean for the Arts in the School of Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 2021, he was named the Chazen Family Distinguished Chair in Art at UW-Madison. He studied in London at the Royal College of Art.

With “Dark Matter,” the British-born, Wisconsin-based artist, barber and professor invites the public to witness his self-transformation and consider their own. The exhibit at MMoCA, 227 State St, Madison, runs through April 2. It examines issues of personal identity, cultural representation and self-determination in ways that are both nuanced and provocative.

Guests browse through 30 years of artist Faisal Abdu’Allah’s work at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art.

“What distinguishes Faisal’s work from other figurative and identity work currently going on in contemporary art is the level of thoughtfulness and the concepts he brings as well as the materiality,” former MMoCA curator Leah Kolb told Wisconsin Muslim Journal. “His art makes a statement about the state of the world and particularly about certain bodies within the world.”

Kolb curated Abdu’Allah’s exhibition “Dark Matter.”

“It’s not a quick read,” she observed. “You can appreciate it immediately but then once you start peeling away the layers, you find more and more there. He has this incredible sensitivity to material. The meaning and the materiality of the piece are intricately tied together. He is able to do it seamlessly.”

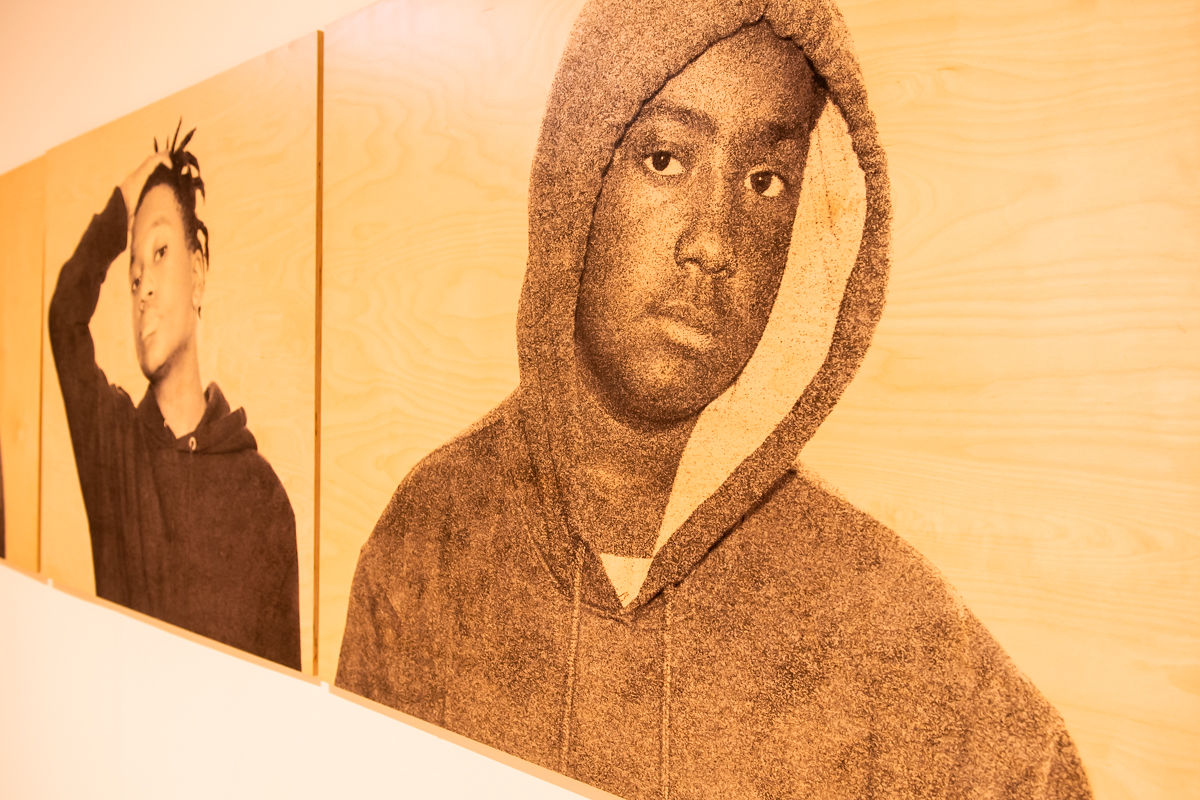

As an example, she cited his series of portraits called “Hair Traits.” There is a performance or social practice part of the work in which he invites visitors into the gallery, gives them haircuts, has conversations with them and photographs them. “He creates the intimacy of the Black barbershop in a place you wouldn’t expect it,” she said. At the same time, he saves the subject’s hair and integrates it into their portraits. “The portraits are literally made out of their DNA. It is a representation of them and it is them, physically and materially. This interactive element with communities distinguishes him from other artists working around issues of representation and identity.”

Witnessing the transformation

Admission to the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, 227 State St., is always free. It features the work of artist Faisal Abdu’Allah with the exhibition “Dark Matter” until April 2.

A Wisconsin Muslim Journal reporter and photographer attended the opening “Dark Matter” Friday. We explored the exhibit, accompanied by Abdu’Allah, who told the stories behind each piece. After the tour, we heard more details in his Artist Talk to a capacity crowd in the MMoCA theater. Access Abdu’Allah’s talk here.

We began outside with Blu³eprint, a commissioned stone sculpture of Abdu’Allah seated in a Belmont barber’s chair. This permanent addition to MMoCA’s collection shows the artist in a barber’s chair, a place he described as safe and secure, where communities come together and share stories.

The title of the piece, “Blu³eprint,” has the power three after “u,” he noted. Embedded in the word is the Swahili word Ubuntu, which means “a person is a person to other people.”

“At my first studio visit with him, he shared his idea of counter monuments,” Kolb said. “The problematic nature of monuments has been in the conversation for decades, but most particularly within the last five years. He suggested instead of funneling money into taking monuments down, what should happen instead is to use that money to commission artists to create counter monuments that will be in conversation with existing ones, presenting alternative narratives, histories and readings. I agree with him that seems like a perfect solution to the public art landscape. It asks us to reassess. How do we reconsider what has been done in the past? “

Madison artist Faisal Abdu’Allah stands beside “Blu³eprint,” a Madison Museum of Contemporary Art-commissioned addition to its permanent collection. It serves as a “counter monument” to invite conversation about monuments and public art.

Upon entering “Dark Matter,” you step into a chronological path through Abdu’Allah’s life, beginning with five portraits against dark walls. “These five people were some of my closest friends, rappers trying to reclaim who we are,” he said. The portrait series, named “I Wanna Kill Sam,” references Ice Cube’s song of the same title.

A portrait series of members of British rap group “Scientists of Sound” addresses reclamation of self-representation against societal stereotyping. It was “instrumental in the artist’s own reversion to Islam and his metamorphosis from Paul Duffus to Faisal Abdu’Allah,” exhibition signage explains.

Music was important to them and has remained a big part of Abdu’Allah’s life, he said. “The UK is an intersection of influences from North America, the Caribbean (where Abdu’Allah’s parents and older siblings left to move to London), the African continent, South America; we were getting information and culture and music from all walks of those spaces,” he said.

“At the time we were listening to (the American rapper) Ice Cube’s album Death Certificate. It had the song, I Wanna Kill Sam. Essentially, it was talking about young African Americans being sent off to fight for America and the American dream, then to come back and not actually being able to actually participate in it or be given the credit that they deserve.

“That piece came out of that. Their hands are over their waists and their heads are bowed, symbolizing my rebirth. You go from one state to the other. You come out of the darkness and go into the light.”

The communal space of the Black barbershop has been central to Faisal Abdu’Allah’s life and work.

The next thing you see is “a drawing that I did not long after my conversion,” Abdu’Allah said. It is handwritten in English text. “I wrote with my eyes closed. This is the part where you let things go, like bloodletting, taking a lot of things that were potentially causing you harm out to make yourself whole again.”

From here, among walls of white, “is the beginning of Faisal Abdu’Allah having a presence and thinking about how art can index and tell stories.

“When I reverted (converted to Islam; Muslims use the word “revert” to signify going back to your original state), it opened my world,” Abdu’Allah said. “There is a level of invisibility for artists who look like me. There is an idea out there that we only talk about one thing; that’s not true. Two, that we are not conceptually smart enough; yeah, we are! And three, that art doesn’t have any value. Yeah, it does.

“As Faisal, I’d go to an exhibition, for example, and an artist from Pakistan or India or Malaysia would say, ‘Oh, Faisal, salam aleckum. Immediately, there was an access point, a sense of love and tenderness and acceptance which is within the Muslim faith.”

The new life

Bottom left: Artist Faisal Abdu’Allah poses with Korey Baker, Jr., 13, the subject of the portrait beside them.

In the series “Hair Traits,” Abdu’Allah created a screen printing of subjects, using paper with adhesive on which he sprinkled a fine powder that incorporated subjects’ hair.

After rebirth is new life. We step into the barbershop. A barber’s chair on a podium takes center stage. Photographs of haircuts Abdu’Allah gave cover a wall.

“I started cutting hair as a student just to make money and I realized this is a wonderful social space where you meet people. They open up to you. It has been an interesting space for communities to share stories. It is a very secure and private space.”

“As I utilize people from the shop, I cut someone’s hair and photograph them,” he explained “That was my case I’d carry all my tools in,” he said pointing to a case on exhibit. “I’d carry my tools by day and in the evening, it would double as a DJ case.”

Abdu’Allah had worked in a barbershop on the northwest side of London in Harlesden, where he grew up. As a child, he’d go to the barbershop and read comics. “That’s the way I came to understand line and form, learned to draw.”

A collection of Black Panther comics is featured nearby. “It is important to include them to talk about identity and aspirations and black futurity,” he said.

Hair and an exploration of identity

The plan was to have clients’ hair incorporated in the work, he said. “For the past five years, I have also been cutting my own hair. And, because of Covid, it became aligned with the Blu3Print, where it says ‘my humanity is tied up with your humanity.’ I use my own hair inside their depictions, so I am inside of them. In some ways, we are integrated as one unit.

“This piece talks about me in the community, my aspirations for youth in the community and how art should also speak to the local populace.”

Some people from the community appear in Hair Traits and other works in the exhibition. During opening night, those models from the community are walking around, viewing their own portraits on display.

Different perspectives on the Garden of Eden

In the center of the exhibition, there is a conceptual installation called “The Garden of Eden,” a large box with two different entrances. Those with blue eyes enter through one door while those with brown eyes enter another.

When blue-eyed people enter, they find themselves in an inner chamber with reflective walls. They only see themselves. The brown-eyed people are outside the inner chamber and can observe them. “It is very much like life,” Abdu’Allah mused. “There are people who know what the deal is while others are tucked away in their insular world.

“In some ways, this is also a metaphor for my body,” he said. “When I was a kid, I’d lie on my back, close my eyes and look at the sun through my eyelids. It would always be red. I’ll always remember that red glow when I closed my eyes. That was the only way I could feel at one with my body and slow myself down. I’d close my eyes and wouldn’t be distracted by everything around me.

“That’s why I put it in the middle of the show. As you come out, you go into another experience.When you come out, I feel like you’re enlightened,” Abdu’Allah said, “the transitioning from darkness to light.

“And over here, we have the Masons who always seek more light,” he said, walking toward larger-than-life portraits in a bright room. “That is the essence of who they are as human beings,” he said. “When you come out, you have a good idea what Dark Matter is about.”

Faisal Abdu’Allah made the installation “The Garden of Eden” in collaboration with Sir David Adjaye. It explores the privileges given to certain people based on “the nuances of their genetic matter,” exhibition signage explains.

Ovet Hughes and Hertis Smith stand before their portraits. Artist Faisal Abdu’Allah said he wanted to honor these Masons who work outside of the public spotlight for the good of the greater community.

“The beauty of the Masons is that they don’t have a particular religion they follow. The main goal is to be a good human being, a way in which a group of thoughtful, caring people can be part of an organization that cares about the community,” he said.

“When you go to the end, you go past my early drawings from the Malcom X series on to the patents,” he noted. A display on a wall at the end of the exhibit features black inventors from the 19th century who made devices like the ironing board that are still useful in our everyday lives. “It signals a point of becoming and that there will be more things we will be able to unpack, convey and illustrate for a wider audience.”

Faisal Abdu’Allah incorporates young people into his interactive portrait series “Hair Traits.” “Young people are very much a part of my work,” he said. “It is extremely important they see themselves as seen.”

Artist Faisal Abdu’Allah poses with his subject Angel Garcia, 12, of Madison.