© Photo

Courtesy of Yasmine Mohamed Ahmed

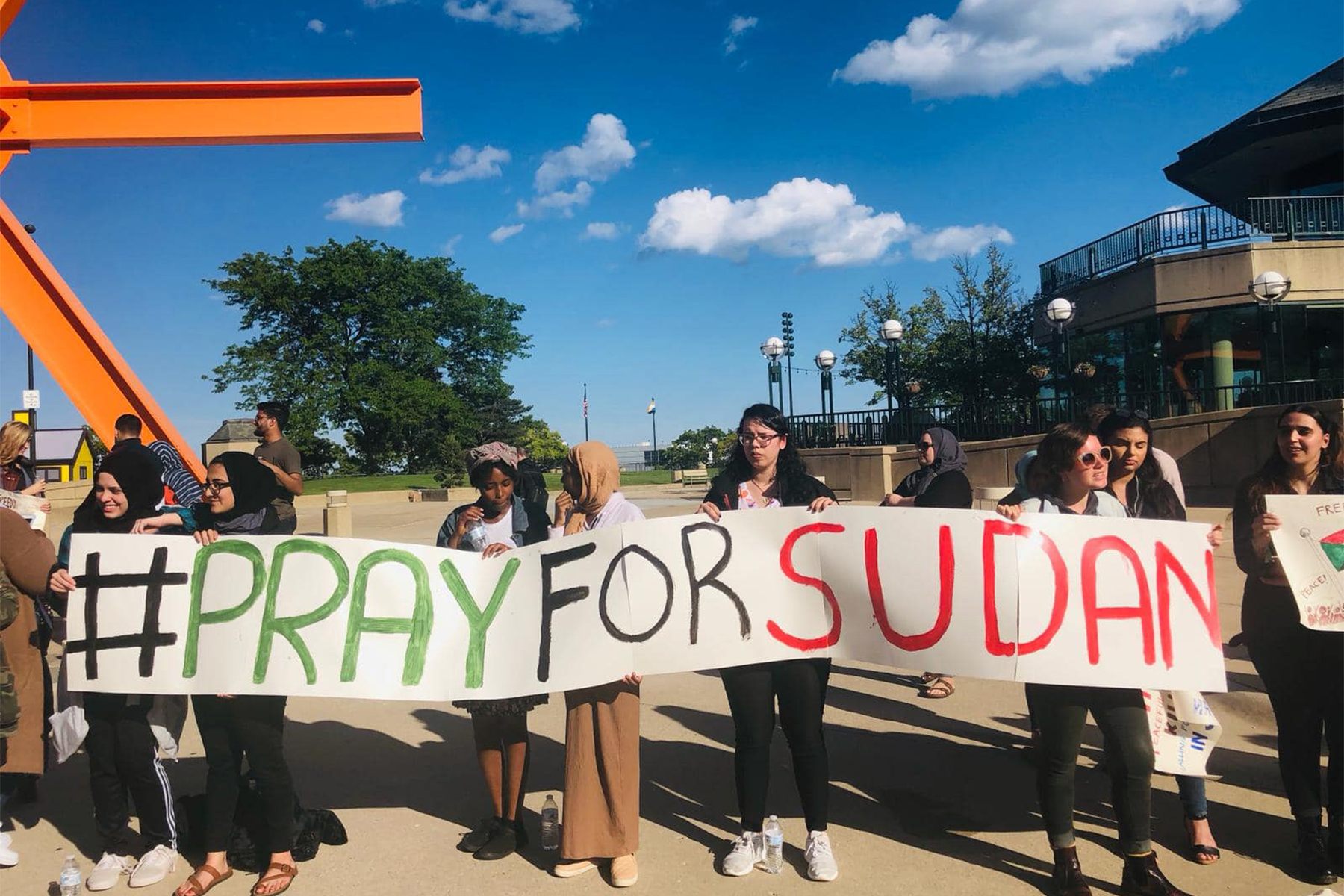

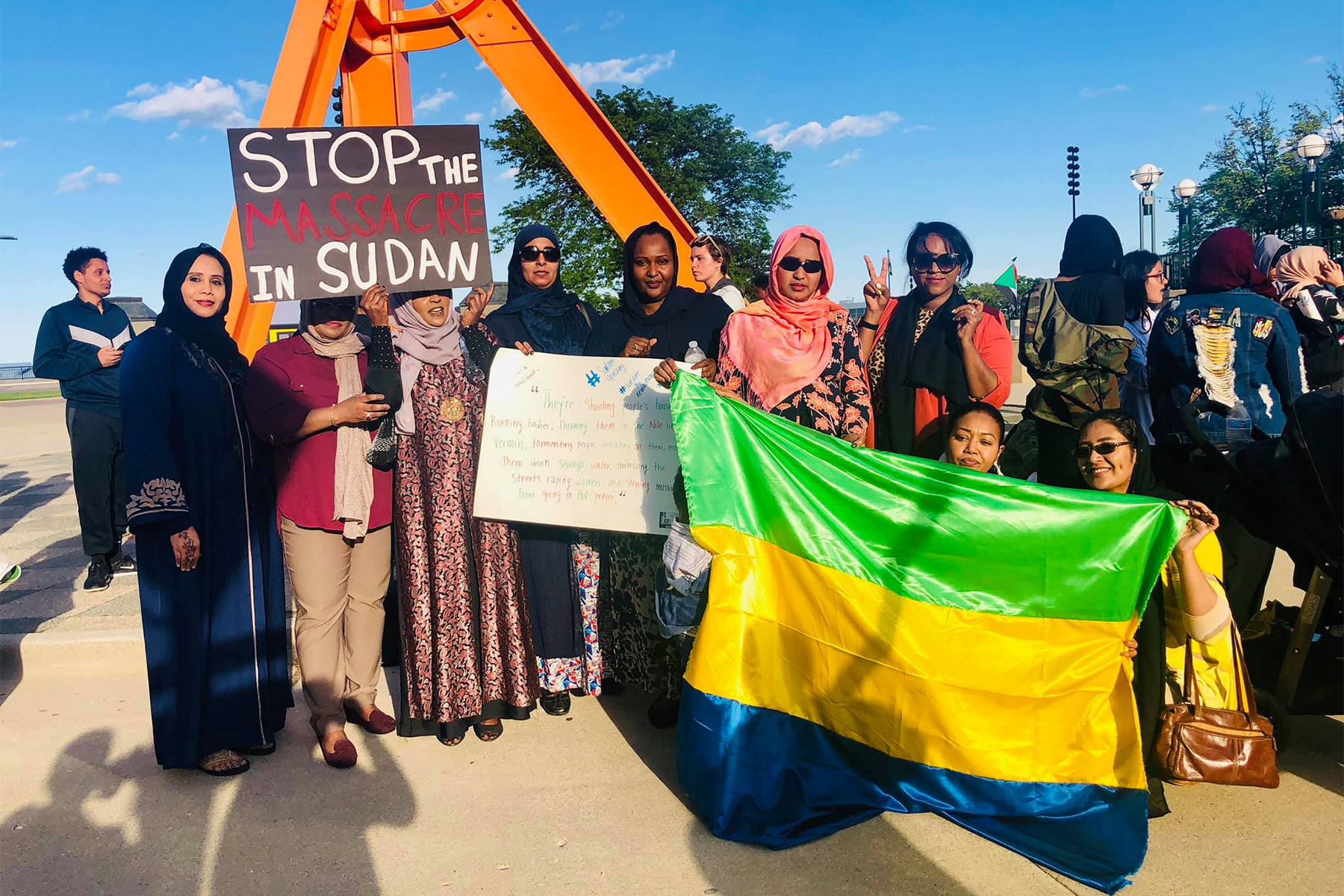

On June 13, a group of about 70 members of the Milwaukee Muslim Community rallied on the plaza at 941 E. Wisconsin Avenue to support protestors in Sudan whose movement had achieved a major victory last April before being subject to a brutal military crackdown in early June.

Rally organizers Yasmine Mohamed Ahmed, Halah Ahmad, and Reema Ahmad acted in response to news of as many as 100 civilian deaths when forces of the Sudanese military attacked a protest camp in Khartoum, Sudan’s capital.

Yasmine Mohamed Ahmed and Halah Ahmad were also speakers at the June 13 event, calling for “attention to the crisis in Sudan and the Sudanese people’s call for freedom, peace and justice,” Halah Ahmad wrote in an email.

“If we stay silent, if we turn the other cheek, we are no better than those who are committing these crimes,” Yasmine Mohamed Ahmed wrote in an email following the event. “I . . . will do whatever I can because I AM Sudanese at the end of the day. The blood of Sudan flows through me . . . I have family members living there who are currently suffering and are scared, my father is from there. I can’t sit back and not care about something that makes me who I am.”

Ms. Mohamed Ahmed was the original organizer of the June 13 rally. “I was already getting messages about whether or not there would be a rally and once Halah offered her help, the ball really started rolling,” she said.

Other participants and chant leaders included Mohammad Mustafa, Wiam Elkhalifa, Ehab Mousa, Hind Abd Elsalam, Tahleel Mohieldin, and Salah Gamar. Many of the rally attendees were Sudanese-Americans.

Hopes for a Sudanese Arab Spring ran high when the thirty-year regime of dictator President Omar al-Bashir ended in April after a series of “mass protests” against his government.

The military coup that deposed Bashir promised a swift transition to civilian rule. However, when progress was stalled and the military showed no signs of surrendering power, protesters in large numbers again took to the streets.

Days of peaceful protest demonstrations were followed by a night of terror when Sudanese soldiers pulled protestors out of their tents and beat them with sticks, raping women and opening fire on those who tried to escape. Protest groups claimed dozens of people were killed by the military, their bodies dumped in the Nile.

The attack on protestors was led by Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan, nicknamed “Heti,” who heads the paramilitary Rapid Support forces, commonly known as the Janjaweed. Hamdan is now in charge of the capital city of Khartoum and is considered the “de facto” ruler of Sudan.

The notorious Janjaweed militias were formed in the early 2000s in response to a rebellion by the Sudan Liberation Army on behalf of the non-Arab population in the Darfur region of southern Sudan. The African people of Darfur claimed they were being exploited by the Nile Arabs controlling the capital and most of the wealth of Sudan.

Early on, the SLA experienced a string of victories against a disorganized and apparently unmotivated Sudanese army. However, with the formation of the Janjaweed, Bashir had located a winning strategy – attacks on the villagers of Darfur. The Janjaweed were essentially marauders preying on the innocent in what was sometimes called the Land Cruiser War, named for the vehicles the militias pulled up in when they arrived to terrorize a village with rape and murder.

The Janjaweed attacks were responsible for a massive refugee and human rights crisis. In 2006, the United Nations stepped in and negotiated a peace agreement favorable to Darfur, but the attacks continued for a time and UN peacekeepers were eventually sent to the region. However, Bashir remained in charge, backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Sudan, with a population of about 40 million people, has institutional and political strengths that could lead to a successful transition to democracy, with professional elites, women’s groups, and pro-democracy political parties that have continued to function despite the country’s lapses into dictatorship.

Experts agree that if Sudan’s prospects for its own Arab Spring are crushed, it could further destabilize a region that has had its share of disastrous military conflicts, like those in Syria and Yemen. The Sudanese generals who currently run the country are allied with powerful economic interests and described the by the New York Times as “business tycoons” in their own right, who control large sectors of the economy and will therefore be even more difficult to dislodge.

After the violent crackdown on protestors in early June, the Forces for Declaration of Freedom and Change, the umbrella organization representing Sudan’s pro-democracy groups, has called for a three-year transition to democratic rule. Activists recently called off a general strike in efforts to avoid further escalation while asking for the resumption of negotiations.