MILWAUKEE’S FORGOTTEN IMMIGRANTS FROM 1890s BUILT EARLY ARABIC-SPEAKING COMMUNITY

Posted by Wisconsin Muslim Journal | Jun 8, 2018

As the Assistant Archivist for the Milwaukee County Historical Society (MCHS), Steve Schaffer gets many requests from individuals trying to fit together a trail of breadcrumbs that vanish over the horizon of a distant past.

One such inquiry involved archival records pertaining to the early Arab community in Milwaukee. That exchange led to the reprint of this article, from the Society’s Autumn 1984 issue in the Historic Messenger.

I knew we had some information on the Lebanese Community in Milwaukee, because a recent researcher visiting MCHS was, in fact, documenting the history of Lebanese communities throughout the United States. The City of Milwaukee was one of her stops this year. We have a folder within our Churches Collection, MSS 1867, dealing with the St George’s Maronite Catholic Church, and the researcher found this material quite useful.

So when a local reporter asked me about the early Arab community in Milwaukee, the question intrigued me. It gave me a chance to delve into what I think to be one of our most interesting holdings at MCHS, our immigration records.

In early 2017, students from the local Islamic School visited MCHS and, during the course of their exploration of the Harry Anderson Research Library’s naturalization records, one of the students found an ancestor who had immigrated to the United States from Palestine. The ancestor had completed his paper work at the Milwaukee County Circuit Court.

Prior to March 1941, and as early as the Territorial Period before Wisconsin Statehood and Milwaukee’s incorporation, immigrants seeking American citizenship could complete their naturalization process at the local circuit courts. Thousands of people in the region did so. As the repository for Milwaukee County Government records, these document are housed in our archive.

– Steve Schaffer

This 1984 article by Dr. Robert C. Delk was an additional, unexpected, but pleasant discovery for Schaffer. The job of archivists is to continually learn, both about professional methods and, more importantly, about the collection of historic materials they are entrusted with. The question about early Muslim records in Milwaukee was an opportunity for Schaffer to explore.

The text presented here is a word-for-word reproduction of Dr. Delk’s article, with the permission of the Milwaukee County Historical Society. Even though it was written in 1984, it does not focus on any events from that time. Instead, it is a snapshot of a historical study, about an era nearly one hundred years prior to when it was written three decades ago.

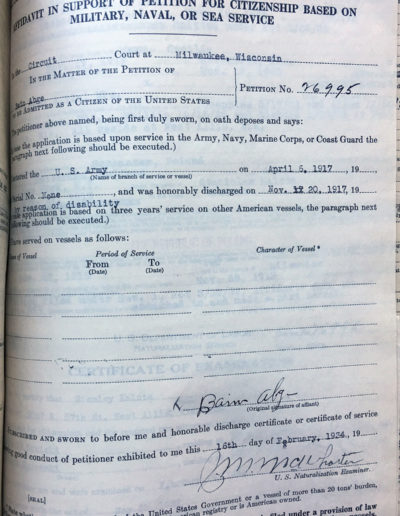

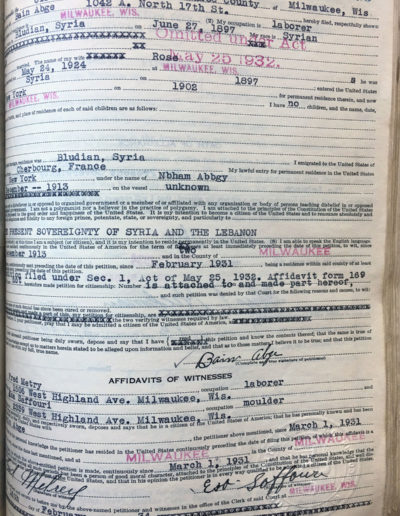

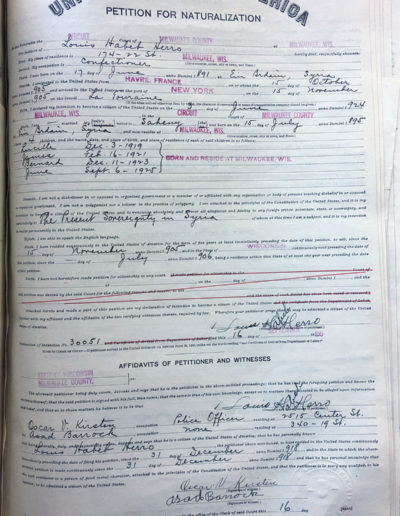

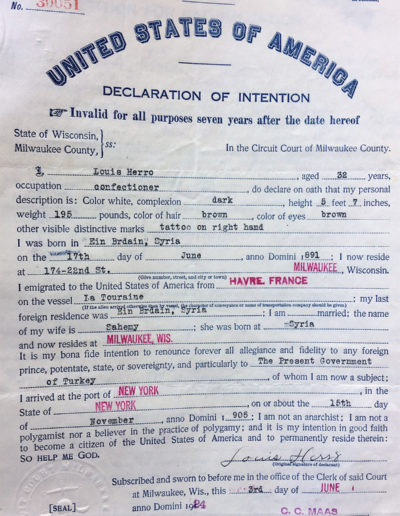

Included are also some images of naturalization papers of United States citizens living in Milwaukee of Arab descent. Many of the early Arab immigrants to Milwaukee were Syrian, Lebanese and Palestinian Christians, they were soon followed by their Muslim brethren, mainly from Palestine. Many descendants of these early immigrants continue to live in Milwaukee.

Early Arabic-speaking Immigrants in Milwaukee

Dr. Robert C. Delk

An observant citizen of Milwaukee may have noted very early in the 1890s that another new ethnic group was represented in the city. The Milwaukee Police report for 1890-1891 shows the arrest of one ‘Arabian’ in that year, but no details are given. The “Milwaukee Journal” of June 29, 1891 reported that there were about 100 Syrians living in the city. According to one of their group, some had arrived in the United States about three years earlier. They banded together and settled on Huron Street in the extreme east end of the city near the mouth of the Milwaukee River. About seventy-five of them, including six women, lived in a two-story frame house at 138 Huron where they were led by “a sort of landlord or boss.” Many of the men were street merchants, carrying their supplies of silk and woolen fabrics, gold and silver thread, and other small items in shoulder boxes covered with oilcloth. The “Journal” reporter made a point of the fact that the Syrians avoided the heavy manual labor in which so many other immigrants engaged, but he added that the police found them “peaceable and harmless inclined.” In their leisure time the men gathered together to smoke improvised narghiles and sing and talk in what the reporter described as “their weird tongue… jabbering away like magpies.”

Among the early Arabic-speaking immigrants was Nicholas Mubarack (Barrack). whose experience parallels that of many others. He left his home near the town of Zahlah in Lebanon to find better economic opportunities. On arriving in the United States in 1893, he went directly to Milwaukee to join relatives already here. He lived on Huron Street and worked as a peddler, dealing mainly in candy, fruit, and ice cream. He married a Lebanese girl named Sarra who had arrived in 1895. She added to the family income (eventually they had five children) by making lace to trim petticoats.

The immigrants of the 1890s, including the Herros, the Metterys, and the Nabkeys, set the lifestyle which was to prevail for a number of years. The community grew slowly, marrying within its own ranks. New immigrants were attracted by the reports of their relatives. Some also came, and eventually settled in Milwaukee, because of tales of American life carried back to Syria by concessionaires at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893.

It is interesting to note that during the last two years of the decade the number of Syrians arrested rose considerably. After never exceeding two arrests a year from 1890 to 1897, the number rose to seven and eight in 1898 and 1899. No causes are given for the arrests. Consequently, it is difficult to explain the sharp increase except as a result of the community’s increased size.

The first decade of the twentieth century witnessed changes in the community. As its members became somewhat more affluent, they began to move from the Third Ward into the Fourth Ward around Second Street and to Kinnickinnic Avenue. Some men of the community (e.g., Frank Ayoob, Mike Malik, and several members of the Herro family) had left the traditional occupations to take work as industrial laborers.

1n 1906 some 6,000 Syrian-Lebanese immigrants came to the United States. One of those who found his way to Milwaukee was James Arrieh. A lad of twelve or thirteen, he joined his uncle (a member of the Herro family who had arrived in 1901) in the hope of finding greater economic opportunity. They lived in the newer Syrian community on Fifth Street between Wisconsin and Wells. James worked at his uncle’s fruit stand for fifteen dollars a month and board. Like many of his associates, he had completed only the village school (probably equivalent to the eighth grade) before coming to the United States and was not aware of the schooling available to him here. Besides, his working hours (the fruit stand was open from 6:00 a.m. until midnight) allowed him no time for formal education. Again, like many other men in the community, his original intention was to return to his home village near Balabakk after making his fortune. Instead he married a girl who had come from his village, became the father of five children, and continued to seek his fortune in Milwaukee.

It is possible that Arabic-speaking people other than the Syrian-Lebanese group appeared in the Milwaukee during the first decade of the twentieth century. At least the police reports, which began listing Syrians as a distinct group in 1897-1898, listed arrestees from Arabia in the years 1900 to 1905, and in 1908, and from Egypt in 1904-05. However, these classifications may have been inaccurate, especially since some of the Lebanese may have come to Milwaukee after a sojourn in Egypt.

In the census of 1910, the number of Middle Eastern people in Wisconsin was listed as a separate figure for the first time. The total of 791 included Armenians and Turks as well as Palestinians and Syrians. It is safe to assume that most of these people lived in the Milwaukee area. Probably about 250 of them were Arabic-speaking.

It is certain that for many of them living conditions were poor. A survey of the Fourth Ward (immediately west of the Milwaukee River and north of the North Menominee Canal) taken in 1911 included seven Syrian families. In the general neighborhood some houses had neither running water no toilet facilities inside. In many instances, houses with a common owner had a single outside water hydrant and a privy for the use of all tenants. Cellars were often used as living quarters. Garbage disposal and drainage were poor. In the Fourth Ward area at least six brothels were in operation. Perhaps conditions of this kind help explain the rise in numbers of arrests from 66 in the decade 1900-1909 to 115 in the decade 1910-1919.

Yet there were indications that the Syrian-Lebanese community was developing. James Arrieh, Joseph Herro, and Charles Nabkey took the lead in founding the Syrian-American Men’s Club on April 20, 1914. Membership cost six dollars a year, and meetings were held weekly in St. George’s Hall at Seventh and State Streets. The club’s purposes were to promote fellowship and Americanization among Syrians and to send financial aid to families in Syria. The men’s group, which had fewer than sixty members, was joined by a still smaller women’s group, the Syrian Women’s Progressive league, probably later in the decade.

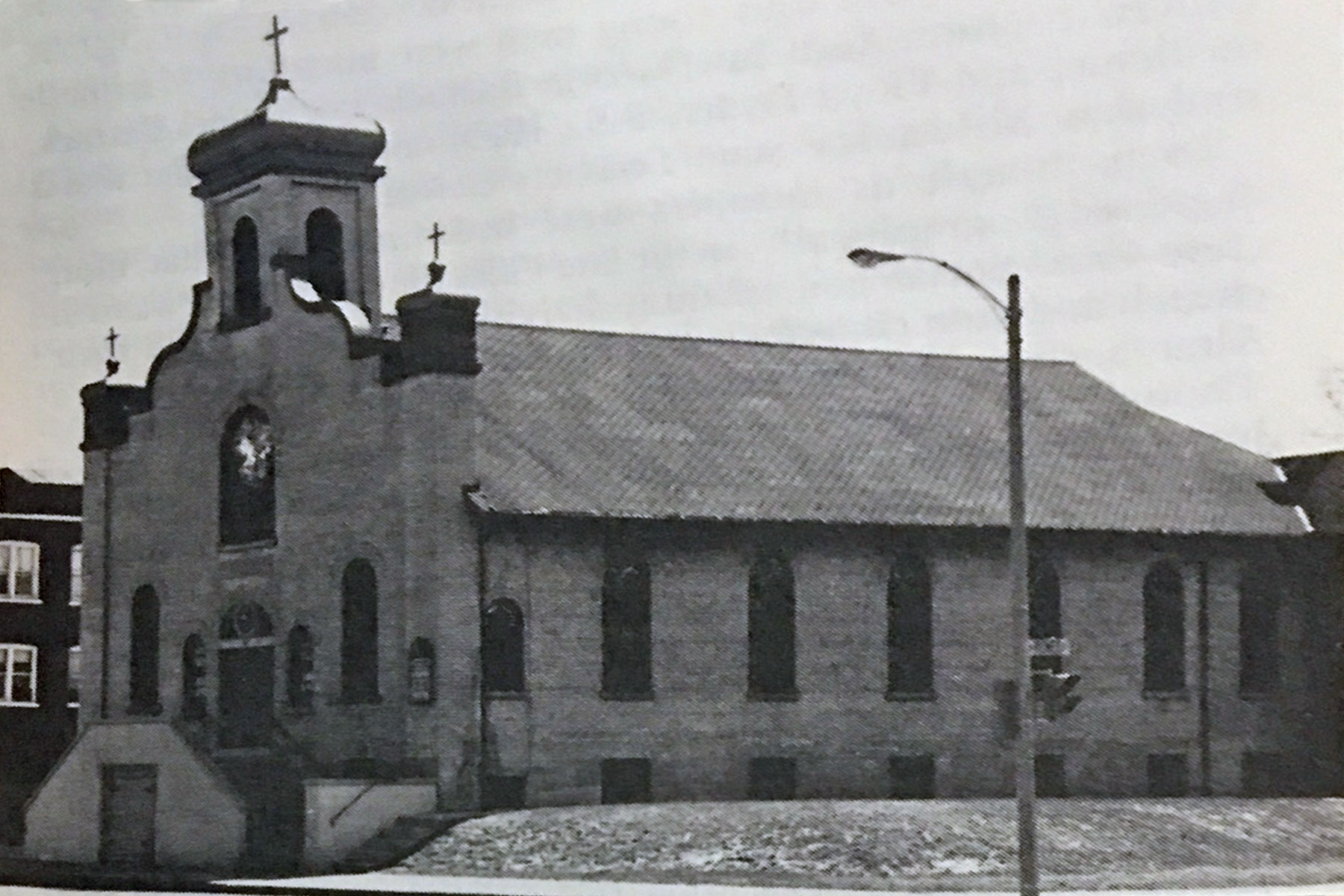

Most of the Arabic-speaking community were Maronite Christians. They held their services in St. Georg’s Hall until 1917 when the moved into the newly-build St. George’s Church in the 1600 block of West State Street. Services were conducted in Syriac under the leadership of Father Peter Nahas. As late as 1945, it was the only Maronite church in Wisconsin.

The community also was included in the New Americans Pageant held at the Civic Auditorium on May 17-18, 1919. The Syrians and thirty-two other groups presented tableaux. Sam Audi, a respected linen merchant, served as chairperson for the Arabic-speaking participants.

By 1920 the census listed 575 Palestinian-Syrian Arabs in Wisconsin. The post-World War I years brought a new wave of immigrants from the Levant to Milwaukee. Typical of the new immigrants were Charles Kashou, who came from Ram Allah, Palestine in 1920, and Charles Bab, who came from Zahlah, Lebanon and arrived in Milwaukee in 1922. Kashou had been a stone mason, but he joined a brother and cousin in the rug business. He returned to Palestine shortly after acquiring American citizenship in 1929. There he married a Palestinian girl who returned with him in 1931. They had four children. In the early 1960s he was still dealing in rugs.

Charles Bab was born to parents who were naturalized United States citizens and who had returned to Lebanon in 1901, two years before his birth. His father returned to the United States in 1913, but the rest of the family was unable to leave Lebanon until after World War I. He went into the apron business with his brother-in-law in Jun 1923, and the partnership continued until 1929. In 1931 he opened a grocery on Wells Street, which he still owned some thirty years later. He remained single, a rare thing in the Milwaukee community, and lived with his sister in a modest east side apartment.

The post-war immigration of the 1920s also brought the first Muslim Syrians to Milwaukee. However, they were few in number and not easily distinguished from their Christian neighbors. Rather typical of the group was a Palestinian named Esa Saffouri. He live quietly with his wife and seven children at 701 West Walker Street. By the spring of 1927, he was employed at Allis-Chalmers as a molder.

During the 1920s there was great interest in assimilating immigrants into the main stream of American life. With that purpose in mind, but also “to develop leadership among the foreign-born and promote appreciation of them through acquainting other Americans with the contribution of their culture,” the International Institute was found in Milwaukee in 1923. The leaders of the Syrian-Lebanese community cooperated with the Institute from the time of its establishment.

Another factor contributing to the community’s assimilation into the American scene was the physical dispersion of its members over a wider area. By 1929 the majority lived along State and Cedar (now Kilbourn) Streets between Seventh and Twentieth Streets. Many of them had confectionery, fruit, linen, and novelty shops in that neighborhood. A smaller number were scattered along National, Kinnickinnic, and Downer Avenues. The community probably numbered about 600 people. From on-half to two-thirds of them had been born in the United States.

A further sign of change was that Arabic-speaking women were beginning to attend school. Syrian women were members of a group of about 900 women of various nationalities who attended classes in the extension division of the Milwaukee Public Schools in 1927-28. Much of this attention was concentrated on English.

In one form or another, language presented problems with which the Arabic-speaking immigrants wrestled. When they arrived, they spoke colloquial Arabic. Those who had above a high school level education (and they were few) knew French. Most of them know little English; a few knew just enough to get along. Very few of the immigrants had time or inclination to acquire further formal schooling, but by the late 1920s, most of the men had acquired a rudimentary knowledge of English in the process of earning their living. About two or three percent of the men knew English well. The younger people of the community knew English, of course, but very few of them finished high school because their parents were anxious for them to work.

Arabic was kept alive among the older people because they patronized their own merchants as much as possible, carried on almost all dry goods business in Arabic, and spoke Arabic at home. The men of the community learned English through use in business dealings with non-Arabs. The younger people used English in almost all their activities and, by the close of the 1920s, were losing their knowledge of Arabic. Because older women still limited their activities to their homes and their social clubs, they knew little English. Higher education was considered the province of men, and few women went beyond the eighth grade. Yet by 1929 at least four young men were attending Marquette University (John Audi, law; George Barrack, law; James Barrack, medicine; and Floyd Hyder, B.S., 1929) and Julia Hyder was a student at Milwaukee State Teachers College.

Even though its members were becoming somewhat more dispersed geographically, in the late 1920s the community was still close knit. Social and cultural activities centered around their church and their clubs (expanded by the formation of St. George’s Altar Society for older women, and the M.C. Club for girls). Though the younger people attended carnivals, public dance halls, and theaters, they took little interest in such things as the Boy Scouts, YWCA, and YMCA, generally preferring their own group.

Marriages were almost always contracted within the group, men sometimes returning to their native villages to find a wife. It was an obvious affront to the community when Fred Saudi, athletic director at the Eagles Club, married an American woman and moved to suburban Shorewood.

Generally speaking, the community was prosperous. It was estimated that about 90 percent of the families owned their own homes, and some owned other real estate as well. Many of the women took advantage of modern conveniences and kept their homes well.

However, there were families in the community who did not own businesses and homes, and who had little success. For example, Elias Faris, who had come from Lebanon in 1913 at the age of thirteen, was a day laborer. As late as the 1950s, he was working as a grinder and mill operator for International Harvester for $1.85 an hour. The community contributed to various social agencies, but it took care of its own members in distress without calling on family welfare and public health agencies.

There are different estimates on the number of Arabic-speaking people in Milwaukee as the Depression decade began. The census of 1920 lists only 28 foreign-born Palestinians and 134 foreign-born Syrians. The same census puts the entire Syrian population of Milwaukee at 349. A somewhat later source estimates the Syrian community at 150 families, from which one would infer a population closer to 500 persons.

The Arabic-speaking group was increased by immigration, though at a lower rate than in the previous ten years. The immigrants were much like their predecessors. For example, George Hishmeh, who arrived in May of 1935, came because Milwaukee relatives sent for him. Like many others, he did not intend to stay; and his wife did not join him until 1946. In Palestine he had been a restaurant and tavern owner, and he came to the United States with money to invest in a business. However, he lost money in his first business venture, a grocery at Sixth and Juneau Streets. For his first two years he was homesick as well as unsuccessful, but his brother would not send him back to Palestine. So he reconciled himself to spending his life in the United States.

During the Depression years, the Palestinian-Syrian community retained many of its cultural characteristics. There was a small degree of social segregation of the sexes. Although dances had become mixed affairs, men and women danced without touching. Marriages were still arranged by families. Charles Nabkey, a community elder, claimed there had been only one Syrian divorce in Milwaukee in fifty years and that was in an unarranged marriage. Most members of the community were small businessmen and property owners. The ideal of community solidarity and intradependence continued. People spoke with pride of the fact that no one in the community had been on public relief during the Depression years. The Depression apparently did not lead members of the Arabic-speaking groups into political dissent. One searches the rolls o the Social Democratic Party in vain to find names of Arabic origin.

At the same time, the community was widening its contacts and developing its human resources. By 1936 some of the men had joined the Masonic Order and other lodges. In the same year, Syrians participated in the Milwaukee Midsummer Festival, presenting an “Olive Harvest in Syria.” James Arrieh and Charles Nabkey served on the festival’s advisory committee in 1938 and 1939 when Milwaukeeans united with the American Federation of Syrian-Lebanon Clubs of America.

Assuming that literacy is an indicator of development, and that the Syrians of Milwaukee followed the pattern of the entire Syrian population of Wisconsin, one can say that the condition of the Syrian community was improving. While 22.8 percent of the foreign-born members over ten years of age were illiterate, only .4 percent of that age group born in the United States were illiterate. Likewise, the lowest rates of illiteracy were to be found in the 10-year to 24-year age brackets (.2 percent for those born in the United States). Among the 134 foreign-born Syrians ten years of age or older in Milwaukee, nine could not speak English, and six of those nine were illiterate. The women still trailed the men in the ability to use English. Of the males ten years of age or older four out o seventy-four could not speak English; two of the four were illiterate. Among the sixty women in the same age group, five could speak no English, and four of the five were illiterate.

By 1940 the number of foreign-born Palestinian-Syrians living in urban Wisconsin had declined from 491 to 413, but this decline had not affected the number in Milwaukee, which was 163 as compared to 162 in 1930. It seems safe to assume that the Arabic-speaking community numbered about 600 people by 1940.

In the 1940s and after the Arabic-speaking community Milwaukee was large enough and active enough to draw attention to its culture and its contributions. It made a marked contribution to the war effort, selling over $76,000 worth of bonds an sending thirty-eight men into the fighting forces. One of them (George Bashour) was killed in Normandy shortly after D-Day.

An observant older citizen of Milwaukee could have noted that the Syrian populace was no longer prominent along West State Street, that their shops had disappeared from that neighborhood, and that James Hishmeh’s linen store at 723 North Milwaukee Street was the last representative of a once-flourishing Syrian business. It would take closer study to learn that younger members of the community had moved into engineering, law, medicine, and teaching.

However, one would have to enter the people’s homes and talk with them for some time to discover that more subtle changes were occurring which worried some older members of the community. Most (slightly over one-half) of the people whom this author interviewed still spoke Arabic in their homes; but almost 30 percent did not. Among their children about 60 percent did not speak Arabic, and the others spoke it only occasionally. About one-third of the community’s young people were marrying non-Syrians. Of Arabic-Syrian customs and traditions, the preparation of foods and the attendance at church and observance of church holidays were the only ones much continued. From one-fourth to one-half of the people probably made no effort to observe traditions in their homes.

Those tendencies were slowed to some degree by the church and the social clubs, and by participation in the folk festivals revived after World War II. However, it probably has been events in the Middle East in the past thirty-five years and the influx of a new type of Arab immigrant that have revived an interest and pride in things Arabic.

© Notice

All content used with permission from the Milwaukee County Historical Society