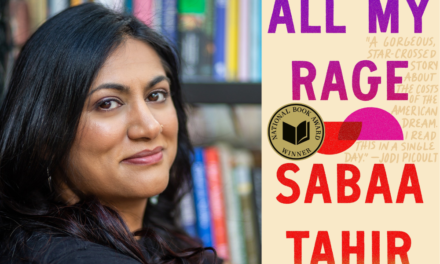

Jasmine M. EL-Gamal as “Muslim is Not an Insult” for The Atlantic

Amir Levy / GETTY

Donald Trump recently retweeted a doctored photo of the Democratic congressional leaders Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer wearing a traditional Iranian maghnaeh (headscarf) and amameh (turban), respectively, and accused them of sympathizing with Iran’s supreme leader. The image was disturbing, confusing, and—given that hate crimes against Muslims and those perceived to be Muslim are a growing concern—dangerous.

In response to the tweet, the White House press secretary told Fox News that the president was “making it clear that Democrats are … almost taking the side of terrorists and those who were out to kill the Americans.” But if the president simply wanted to link Democrats to Iran’s supreme leader, he could have tweeted any number of images that did not include them wearing attire worn by millions of Muslims around the world, none of whom has anything to do with ayatollahs or terrorism.

The president’s tweet was personal for me. I’m a first-generation American from a Muslim family and, until 2017, I spent my entire career in public service, including eight years as a civil servant at the Department of Defense, where I advised the department’s leadership on Middle East issues. As the daughter of Egyptian immigrants, working at the Pentagon was more than a job—it was a way I could show my parents that their sacrifices through the years were worth it. I would see admiration, sometimes surprise, reflected in the eyes of officials from the Middle East when they saw a young woman of Arab descent sitting behind the secretary of defense at a meeting. So when I read about how my colleagues Rumana Ahmed and Sahar Nowrouzzadeh were alienated or pushed out under the Trump administration for being Muslim or Iranian, I was devastated—not just for them personally, but also for the image and spirit of our country.

This is not the first time the president has twisted facts or conflated issues as they relate to Muslims to score political points with his base. Almost a year before he won election, Trump called for banning Muslims from entering the United States—a policy that evolved into what is now known as the “Muslim ban,” with hugely detrimental effects. On the campaign trail in 2016, he stated that “Islam hates us,” portraying Islam, and by extension Muslims, as an angry, monolithic “other” dead set on destroying the American way of life. With those three words, Trump set the tone for the years to come, fueling an “us versus them” narrative that has widened deep fissures within our society.

I grew up in both the U.S. and Egypt and have regularly been asked to explain each country’s culture to the other. Like anyone bicultural, I was taught to be wary of generalizations. After college, I served as a translator with U.S. troops in Iraq, and I became acutely aware of the importance of symbolism. Speaking to Iraqis and Americans in their own language, I could see clearly their shared humanity; to me, they were more similar than different. They couldn’t understand one another’s words, so, at least initially, they focused on one another’s clothes: a black veil, a checkered scarf, mirrored Oakley sunglasses, an orange jumpsuit, military fatigues, a suit and tie. Every garment and accessory evoked a stereotype and, based on the individual’s perception, represented either safety or danger. I learned that without dialogue, breaking barriers or creating bonds between the two cultures was impossible.

If the right words can defuse tensions, the wrong ones can amplify them, as Trump seems to understand. He has proved adept at harnessing people’s fears and grievances. He’s not incapable of reaching out to communities to temper their anxieties, but he does so selectively. During his first address to Congress, the president denounced both racism and anti-Semitism. He spoke about Black History Month and the then-recent vandalism of Jewish cemeteries. But in the same address, the president simply referred to “the shooting in Kansas” to describe an attack by a white American against two Indian men he had thought were Middle Eastern. That the attacker yelled “Get out of my country!” before pulling the trigger did not warrant a mention in the president’s address, nor did the fear that by then had begun to grip Muslim communities across the U.S. due to a rise in Islamophobic attacks.

Dehumanization is an easy trap to fall into. If you’ve never met a Muslim, it can feel impossible to relate. If the only time you hear about Muslims is in in the context of a negative event, your mind begins to link Islam to such events. When the president tweets an image of two Democrats wearing Muslim clothing and his spokesperson pairs that image with words such as terrorism, they are going well beyond criticism of Democrats’ political positions; they are implicitly linking Muslims and their appearance to danger. For American Muslims, this means stripping away our identity as Americans and telling us that we don’t belong “here,” but rather in faraway lands and cultures that are different from, and dangerous to, “yours.”

This type of Islamophobia, like anti-Semitism, racism, and other dehumanizing biases, is harmful not just to Muslims, but to all Americans. The president’s use of Islamophobia as a weapon has undermined our country’s values, tarnished our image abroad, and weakened our ability to lead by example. Worst of all, it has made us scared of one another.

The day after Trump’s election, I walked around Manhattan in the early hours of the morning in a daze, wondering what his presidency would mean for my family and the millions of other minorities in America. The streets were empty, other than the occasional police car or yellow cab. That night, it felt like something had changed. I walked into my hotel’s lobby just as Trump was addressing the country. He said, “Now it’s time for America to bind the wounds of division … come together as one united people.” I remember hoping that he meant it. I remember thinking that I would support his efforts if he did. Three years and many derogatory tweets later, it is clear he didn’t.