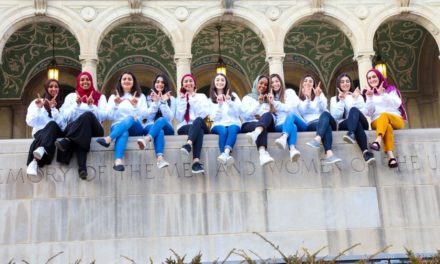

From Left: Dr. Ojo Tunde Massey Ferguson of Nigeria; Dr. Hafsa Lukwata Sentongo of Uganda; Dr. Muktar Beshir Ahmed of Somaliland; Dr. Sebastian Ssempijja Of Sebastian Family Psychology practice in Glendale.

The world is swimming in refugees. The Migration Policy Institute reports that what it calls “global displacement” had “reached a record high of 68.5 million people by the end of 2017.” That number includes those “formally designated as refugees” as well as “internally displaced persons” and “asylum seekers,” according to statistics gathered by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Project 1 Billion was founded by the International Congress of Ministers of Mental Health and Post-conflict Recovery to formulate a “mental health action plan.” According to a report issued after a conference in Rome in 2004:

The social and human costs of mass violence are staggering. More than 1 billion persons in over 47 countries today have been affected by mass violence, embodied in the experience of war, ethnic conflict, torture and terrorism. The last century has been described as the “refugee century” [but the] intentional targeting of civilians and human suffering [are] showing no signs of abating in the 21st century.

There are more displaced persons in the world today than at the end of World War II, when the number of refugees was already considered staggering.

Among the many problems of the displaced are mental health issues like PTSD, depression, substance abuse, and other trauma-related illnesses resulting from violent conflicts, the kind that cause people to flee their homes and become refugees.

Milwaukee has its share of refugee communities, fleeing violence in Sudan, Syria, Somalia, occupied Palestine, Laos, and South and Central America. And Milwaukee has its share of people traumatized by poverty and the violence of neighborhood streets where random gunfire frequently has tragic consequences. Often, the trauma suffered by these communities surfaces in the school system and can derail the future for those trying to rebuild their lives after a violent past.

In Glendale on Monday, a group of mental health providers that included representatives from MPS, UWM, Walkers Point Community Health Clinic, the City of Milwaukee Health Department, the Islamic Resource Center, and Rogers Behavioral Health heard the presentations of three visitors from Africa, all of them working in the field of mental health and dealing with displaced and traumatized populations within their own countries.

The group was brought together by Dr. Sebastian Ssempijja, who provides mental health services for MPSthrough the School Community Partnership for Mental Health (SCPMH), a program that now includes 29 local schools with refugee populations.

Dr. Sebastian, as he is called by his clients, heads the Sebastian Family Psychology practice, which has its offices in Glendale. There, representatives of the Milwaukee-area mental health provider community met Hafsa Lukwata Sentongo of Uganda, Muktar Beshir Ahmed from Somaliland, and Ojo Tunde Massey Ferguson of Nigeria. All three are involved with government-run mental health programs in their home countries. Dr. Hafsa is the director of the mental health and substance abuse department at the Ministry of Health in Uganda.

Dr. Ojo Tunde reported that Nigeria has 7 regional and psychiatric hospitals, one in each political zone. Since 2010,the country has implemented a model that integrates mental health and primary care. Patients see a psychiatric nurse supervisor or psychiatric consultant once or twice a month. Nurses distribute medication to patients and supervise workers.

This community-based approach is necessary, said Dr. Tunde, because Nigeria is in a “resources constrained situation.” The country has a population of 200 million and only 200 psychiatrists – that’s one psychiatrist for every million people.

Uganda is in similar straits, with a population of 45.7 million and only 32 psychiatrists, said Dr. Hafsa. Somaliland has four psychiatrists for 4.5 million people, according to Dr. Beshir.

Community-based mental health programming is a necessity in these countries.

That means, rather than relying on a hierarchy of doctors directing mental health services, provision of services is more ground up and includes primary care practitioners (doctors, nurses, psychologists, health workers), traditional and spiritual healers, family members, and school counselors, as well as local and international NGOs.

This model is very similar to one that is being encouraged in the United States, where the problem of resource allocation, while not as extreme, results from the large number of uninsured to the disproportionate need for services on the part of children and adolescents.

Dr. Tunde pointed out that, while there are only 200 psychiatrists in Nigeria, there are 1,000 Nigerian psychiatrists in the United States and 500 in the U.K. Developing countries tend to suffer from what Dr. Tunde called a “brain drain,” as people who have been expensively educated seek an income to match.

In Uganda, “We are still very naïve and very raw as far as community mental health is concerned,” Dr. Hafsa said. “A Mental Health Act was just passed on Christmas Day – a Christmas present to people with mental health issues,” she said. And a 50-year plan is being implemented to incorporate mental health strategic planning into the Ministry of Health. One of the aims, Dr. Hafsa said, is to reduce the stigma associated with seeking mental health treatment in Uganda.

In addition, Dr. Hafsa said, “the witchcraft issue is very high on the agenda” in Uganda, it can hinder medical care but until there is more opportunity for education, psychiatrists may see the work of traditional healers as “complementary,” while religious leaders say, “We cannot be bundled with these people.”

Nigeria may have “only 200 psychiatrists, but there are thousands of traditional healers and pastors who work for next to nothing. We work with traditional and spiritual healers to deliver services. This is also part of our collaboration,” Dr. Tunde said.

In developing countries as well as in the United States, primary care providers are often the first line of defense in combating mental health issues. In Somaliland, said Dr. Beshir, “3 out of 4 people visiting hospitals have serious mental disorders.” While Somaliland is now peaceful, the mental disorders are the result of many years of war. Hospitals in Somaliland are fortunately “100 per cent free of charge,” said Dr. Beshir.

However, in Nigeria, “we have the same treatment gap you see everywhere. For every person who comes to receive treatment, 8 or 9 won’t come to the hospital,” said Dr. Tunde.

Kim Peterson, the Rogers Behavioral Health community outreach representative, said she was struck by the similarities between problems African nations are dealing with and those local providers face. “We have the same discussions about having entry-level people doing more” to provide care, Peterson said.

The key is that mental health services must be culturally appropriate. In providing mental health services, there is no “one size fits all.” In Africa, Dr. Hafsa said, the question must always be “What is their belief system?” She added that, “The cultural competency of service providers needs to be improved upon.”

That lesson, like so many discussed during the session, was one both the participants from Milwaukee and those from Africa could agree on.