Leean Othman said her brother Sinan Othman “was the most selfless and pure-hearted being I have ever known.”

Some people seem to be too good for this world. They care too much, love too much and feel too deeply. They empathize so strongly that the pain of others becomes their own.

That’s what people say about Sinan Othman, a young Milwaukee man who died of a brain aneurysm in 2021 at the age of 30.

“He believed in equity and justice. He hated war, oppression and inequality. Since he was a child, he always noticed and pointed out the injustice taking place around him,” said his mother Enaya Othman, Ph.D., a Marquette University associate professor and founder of the Arab and Muslim Women’s Research and Resource Institute (AMWRRI). Issues of injustice in society at large as well as those he witnessed firsthand took “a large toll on his mental and emotional well-being,” she said.

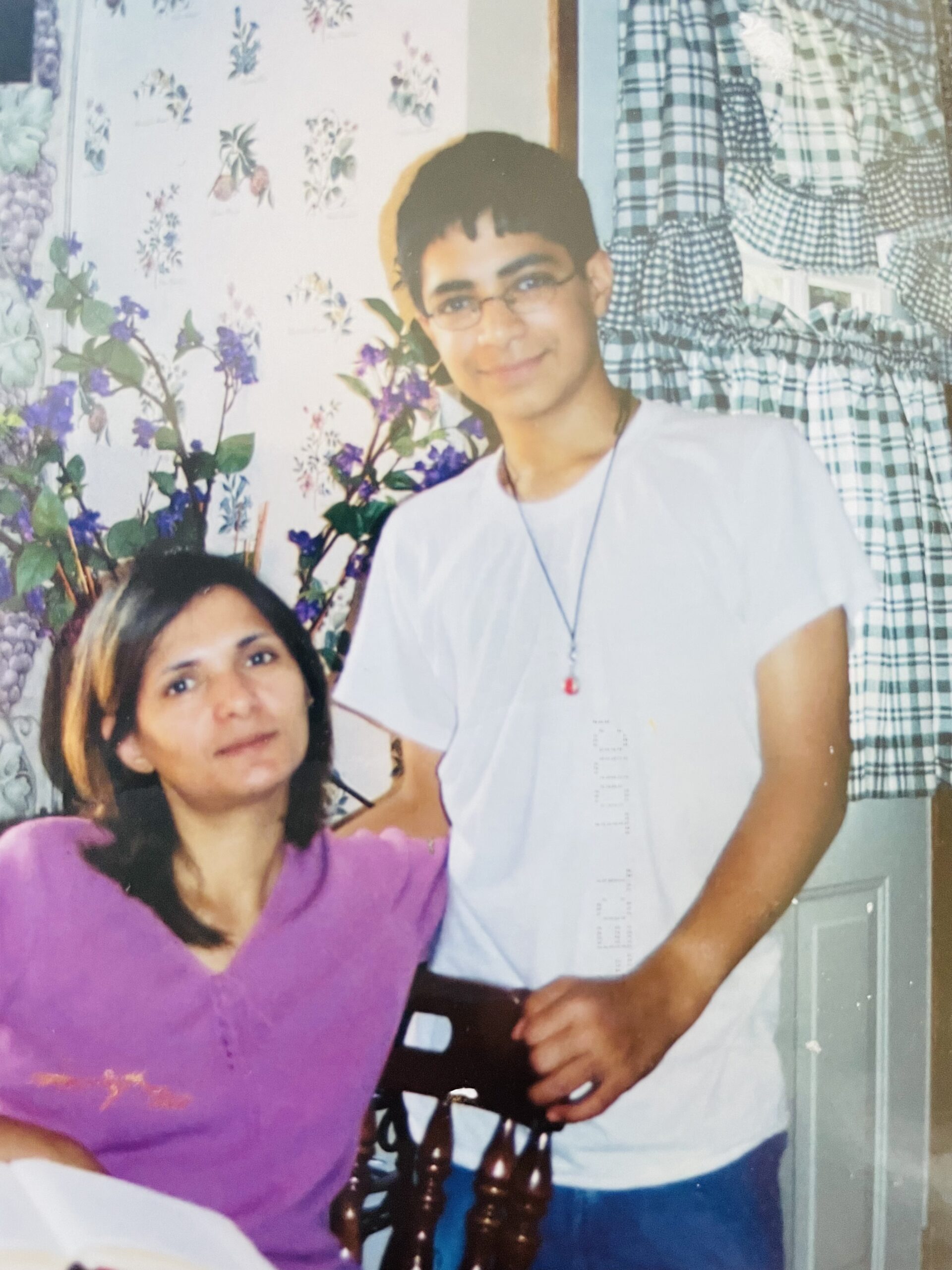

Associate Professor Enaya Othman with her son Sinan

Sinan’s concerns for others and his own experiences with discrimination and prejudice “as a non-white Muslim growing up after 9/11” have strongly influenced his mother’s research, teaching and service, where topics of discrimination and marginalization are central. MU has two classes that challenge students to re-envision disability, “both because of him,” Othman said. She co-designed The Construction of Disability, and created and designed Re-envisioning Disability herself.

Othman organized a conference the AMWRRI and Marquette University hosted in 2022 to deepen understanding of disability and its complexities. She is working on another for 2024.

And now AMWRRI is offering a $6,000 scholarship in memory of Sinan Othman for graduate or undergraduate American Muslim students pursuing degrees in social work, psychology, mental health counseling, clinical therapy, substance abuse counseling, school counseling, special education or disabilities studies. (The deadline to apply is March 15. See how to apply in the scholarship announcement.)

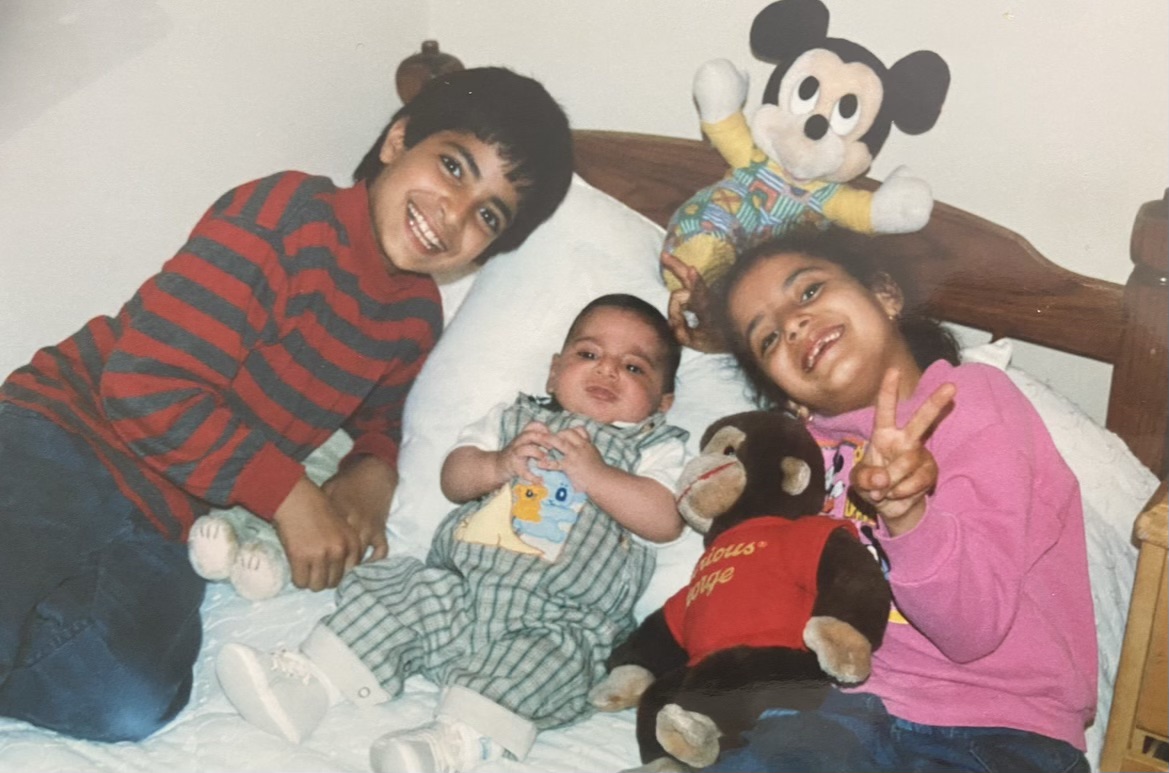

Sinan (left) and Leean (right) welcome baby brother Yaman.

Addressing the shortage of Muslim mental health professionals

The award addresses a need for more Muslim mental health professionals, Othman explained. “AMWRRI, in collaboration with the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, conducted research on the experiences, perspectives and needs of Muslims who have differences of abilities (which encompass both physical and mental health).

“One of our research findings is that more Muslims are needed in professions such as social work, mental health counseling, clinical therapy, substance abuse counseling, school counseling, special education and disability studies,” she said. “Our goal is to address the role of cross-cultural deficiency of therapists or other healthcare providers who not only lack understanding of their clients’ cultures, but also have prejudices towards non-whites. Unfortunately, this has contributed greatly to some people not receiving adequate treatment.”

This scholarship will contribute to the study of disability from a cultural and social perspective, especially with regard to the experiences of second-generation immigrants who struggle with depression or mental issues, Othman said. It aims “to contribute to the education of young researchers and students who aspire to transform the field of disability studies, as well as the practice of healthcare, to be more inclusive and cross-culturally sensitive.”

Sinan Othman, for whom the scholarship is named, was a second-generation Arab American Palestinian Muslim who lived his life trying to make the world a better place, Othman said. “A deep-thinker,” “a non-conformist” and an “intellectual in his own right, he questioned the basis and motives of discrimination in society and inspired me when he was alive to initiate research on the struggles of immigrants and their children to adjust to life in the United States.

“A line of this research focuses on the experiences of people with disability and caretakers who are doubly marginalized due to their ethnicity, religion, gender and also disability. Many research studies among the Muslim population show that mental conditions increased among second generation Muslims.”

In her own research, Othman “had many interviewees who had experiences of therapy in which the therapist assumed the source of mental disorders or psychological problems was in religion or culture. The treatment process can ironically result in more anxiety and depression.”

With her research, Othman aims to raise awareness and cause a meaningful change for a just, equal and inclusive society and system,” she said. “I am sure anything that has the potential to contribute to equity and justice would make Sinan very happy.”

A tender heart

Sinan’s younger sister Leean Othman remembers her brother as “the most selfless and pure-hearted being I have ever known, and I don’t just say that because he was my brother. I really mean it.

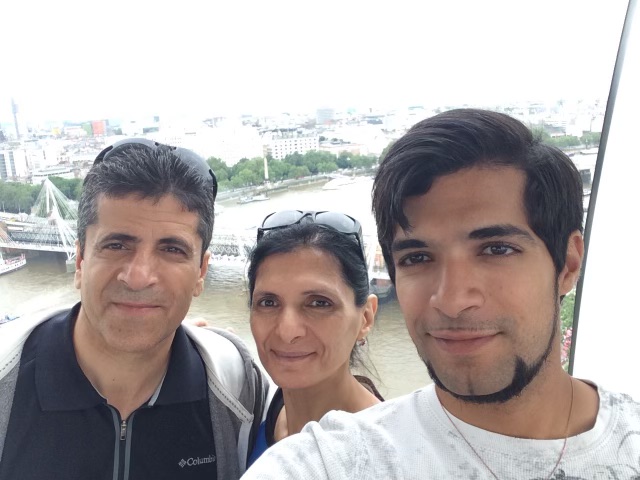

Islam and Enaya Othman. (Back row:) Sinan, Leean and Yaman Othman

“I never came across someone as genuine as him. He was always so caring and protective over me as an older brother.”

When Leean started college, she was unsure about whether she should pursue a law degree. Sinan told her, “No matter what you do, I know you are going to be great,” she recalled.

Sinan called his sister to check on her regularly after she married and moved to a new home.

“He was always so supportive of me and our younger brother,” Leean said. “He truly was a remarkable and one-of-a-kind individual.

“After he passed, I couldn’t believe the number of people who came forward, sharing stories about how he helped them in some way. But, at the same time, I knew I shouldn’t be surprised. That’s just the person he was.”

“He was always ready to drop everything to help not only the loved ones and friends but also strangers, if he could,” Othman said. “When we moved to a new house, he would smile to our neighbors, especially the elderly. He gave rides to people he saw on the side of the road. Although that could be dangerous, he didn’t want to leave even strangers out in the cold.

“He liked to help everyone and anyone. He would help the elderly in our neighborhood by shoveling the snow without them asking him.

“He saw the best in people and was there for every single person he ever came across, even if that meant sacrificing his own needs. One time, he cleared his bank account to give money to a friend who needed financial help.

“He was simple and always content with what he had. As a child and teen, he never asked for specific clothes or shoes. He would wear whatever I bought him.” Othman said. “His sister would ask him what he wanted for his birthday and his response was always the same: ‘Nothing. As long as you’re good, I’m good.’

Islam, Enaya and Sinan Othman

“He had a contagious smile. He was comical, always ready to tell a joke. When he was young, he loved to play video games and spend time with his siblings. He loved to read, and write poetry and short novels.

“Sinan spent his entire life trying to help those around him and make people smile. He was selfless. He was respectful. He never held anger or hate towards anyone. He was always ready to light up the faces of those around him. He truly was a shining light.”

A questioning mind

“Sinan dreamed of and struggled to make the world a better place,” Othman said. “When he was so small and we were in a supermarket, he asked me why people had to pay for food and things they needed.

“He tried to set things right,” she recalled. He cared about the environment and “as a child, he used to pick up every piece of paper or anything people threw on the ground and put it in the garbage.”

Sinan “could not comprehend what has happened to Palestine,” to which he had a strong attachment, Othman said. The family visited both his parents’ childhood homes in Al Bireh in the West Bank every two or three years, and Sinan stayed there for a year when he was a freshman in high school. He played the trumpet and when he was there, he played with a Palestinian group, connecting with them through music.

Growing up as a non-white Muslim in America in the aftermath of 9/11, “he endured discrimination and bigotry,” Othman said. “The atmosphere of Sept. 11 and the media’s portrayal of Muslims, Arabs and Palestinians gave him agony. Why we human beings mistreat and hurt each other puzzled him.”

His history teacher told him, ‘You look like a terrorist.’ He would not call on him to answer questions when Sinan raised his hand. In the school bus, his peers would say things like ‘We don’t want to sit next to an Arab.’”

Sinan didn’t mention it to his parents at the time, but as his all-A grades began falling and he showed stress about school, his mother prodded and he shared the story.

“’Why didn’t you tell me before?’ I asked him.”

“’To protect my sister,’ he told me, since she might have the same teacher in the future.”

Yet, “he wasn’t afraid to be different; he was proud of his background. He never allowed the bitter experiences he endured make him a negative or bitter person. He never allowed the negativities or hardships to stop him from lending a helping hand.”

If you would like to contribute to the Sinan Othman Scholarship Fund, you may make a donation at this link.