Throughout his long career as a community psychiatrist, H. Steven Moffic has tried to implement hineni, or the Jewish principle of standing before God with the words, “Here I am, Lord.”

Hineni is the response of the patriarchs Adam, Abraham, and Moses to God’s call, that moment of saying to God:“Here I am, ready and waiting to do Your will.”

For Moffic, the connection between hineni and his work as a psychiatrist first crystalized in 1966 at Northfield State Hospital in Michigan, when the he was a psychology student assigned to a “practicum” with the seriously mentally ill. Dr. Moffic recounts that he and his then-fiancée Rusti were witnesses to a scene straight out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, with highly medicated patients shuffling around in near-trance states. Instead of fleeing, Dr. Moffic vowed not to turn his back on some of the most neglected patients in modern medicine, but to dedicate his life to “serving the underserved” in the mental health field. “From [a] fusion of compassionate love for the patients and romantic love of my wife, I pledged . . . to serve the most . . . seriously mentally ill people,” he wrote.

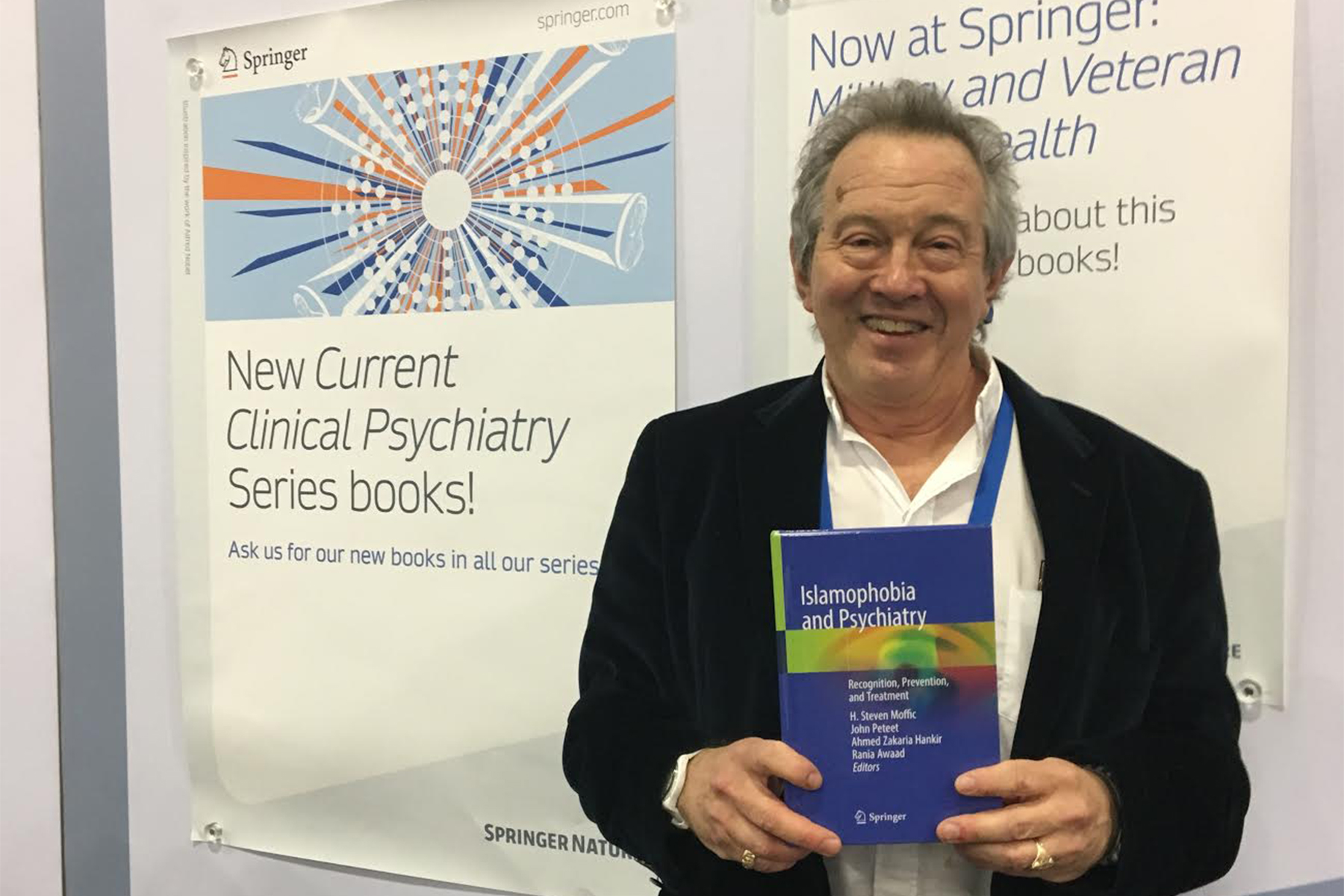

In 2012, Dr. Moffic officially retired from his clinical practice and from teaching at the Medical College of Wisconsin. But his mission has, if anything, only broadened with the release this year of Islamophobia and Psychiatry: Recognition, Prevention, and Treatment by the academic press, Springer International. Dr. Moffic was the lead editor of a team that also included one Christian and two Muslim psychiatrists.

While still in the process of deciding whether to take on the project, Dr. Moffic considered whether it was “useful and appropriate to pay attention to social concerns like Islamophobia – it’s not even a diagnosis. It’s more of a social diagnosis,” pertaining to people who have a “strong fear of Muslims.”

However, as the psychiatrist Renato D. Alarcón pointed out in his review, the book’s “content . . . surpasses the limits of its title” and includes “an exploration of the historical basis of Islam [and] its connections with the current political realities of a convulsed world.”

For Dr. Moffic, the important considerations were, “How does [Islamophobia] translate into Muslim mental health care? Does it make it harder for Muslims to come into treatment? And what about Muslim psychiatrists? Will non-Muslims want to see them?”

Because there was no other book on the subject, Dr. Moffic was hopeful that he and his team of writer/editors would uncover “some new information that was not known, not out there in the literature. . . And I believe we did,” he said.

Part of the learning experience for him was the discovery of “how advanced Muslim physicians were about Muslim mental health. Back in the early middle ages, the first psychiatric hospitals were formed and staffed by Muslim physicians. That didn’t happen in Europe until hundreds of years later – the 1700s or so,” Dr. Moffic said.

In the chapter on “Mental Health in the Islamic Golden Era: The Historical Roots of Modern Psychiatry,” Rania Awaad et al. wrote about the origins of mental health treatments that originated in the Islamic Golden Age – roughly the 8th through the 12th centuries, when Islamic culture was “unmatched in its brilliancy and unsurpassed in its literary, scientific, and philosophical output.”

The book also relates knowledge about “Muslim physicians who came up with concepts and theories that were predecessors of some of our modern ideas of psychiatry, like cognitive behavioral therapy. When the Muslim empire dissipated, all this information seemed to disappear,” Dr. Moffic said.

Another discovery for Moffic was the importance of integrating Muslim patients’ religious beliefs into “methods of treatment,” something that he said, “happens less with other groups” and is “relatively easy for a Muslim psychiatrist to do, but a non-Muslim psychiatrist” may find it more problematic. The book also “covered various sub-groups that hadn’t been discussed in the literature,” including African-American Muslims and the Rohingya, he said.

Two years ago, Dr. Moffic was on a panel in which Muslim, Christian, Hindu, and Jewish psychiatrists discussed Islamophobia as a clinical condition. The panel, he says, “went well” and as a result, a representative of Springer International approached him about doing a book on the topic. His initial reaction was “are you serious, asking me to do this?” Was it appropriate, Dr. Moffic wondered, for a Jewish psychiatrist to take the lead in editing a book about Islam? The Springer rep, who was familiar with Dr. Moffic’s previous work as an editor, replied that he had always “specialized in the cultural aspects of psychiatry.”

The book’s “two big conclusions,” Moffic says, are that “psychiatrists should be . . . talking about [Islamophobia]” and that, “if you have Islamophobia in society,” a broader conversation about the topic is required. “It helps if all kinds of psychiatrists talk about it, not just Muslim psychiatrists.” After all, Dr. Moffic points out, Islamophobia is also destructive “for people who have those beliefs,” and “Muslims are now viewed as invaders by the president, which is an example of how Islamophobia has spread its net.”

Partly as a result of Islamophobia, Muslims who need psychiatric care are one of the most underserved groups of potential patients in the United States, Dr. Moffic believes. One of the book’s goals was to discover “how to welcome them into psychiatric care.”

The book’s publication seems to fulfill a distinct need. Thus far, Dr. Moffic said, it has sold out at every conference and bookstore where it has been presented.

Islamophobia and Psychiatry: Recognition, Prevention, and Treatment, edited by H. Steven Moffic, John Peteet, Ahmed Zakaria Hankir, and Rania Awaad. Springer Int’l, 2019

415 pages • $159.99 (hardcover); $119.00 (eBook)

Individual chapters available upon request.