Michael Wolfe for Religion News

(AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

The latest chapter of protest and resistance unfolding on the streets of America is reminiscent of a peat fire: a high flammability condition that springs up under pressure in parts of a field, rages for a period but then seems to die down, while in fact it is traveling under the surface, out of the spotlight, springing up full-force again in other locations at another time.

This peat fire sprang up as long ago as August 1965, in the Watts Riots that left 34 dead, 3,438 injured. It sprang up in 100 cities again after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in the spring of 1968. Forty-three died and another 3,000 were injured.

After 24 years, a passerby’s video showing Los Angeles police beating Rodney King during an arrest provoked protests that killed 63 and injured 2,383. A quarter-century later, protests following the killing of Michael Brown by a Ferguson, Missouri, policeman injured 13.

When the George Floyd protests broke out this year, the agony and pain were immediately familiar from decades and centuries of heat, threat and insecurity in the lives and neighborhoods of millions of Americans.

Islam has a deep backstory in this drama. The first New World revolt against slavery was led by West African Muslims in the Dominican Republic in 1522. The prolific 19th-century scholar Omar bin Said in the Carolinas and the pre-Abolitionist hero Prince Abdul Rahman Ibrahim in Natchez, Mississippi, were the forefathers of the Black Pride we see today.

You can view highlights of these heroes on the beautiful, intriguing website of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Historians suppose that around 20% of the slaves brought to American shores in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were Muslims — human beings ripped from their roots in West and Central Africa and shipped to slave markets as chattel.

Mostly nameless, these are the forefathers of innumerable Indigenous African American families. They can’t be counted, because in most cases the brutalities of slavery erased all trace of the family links between their times and ours.

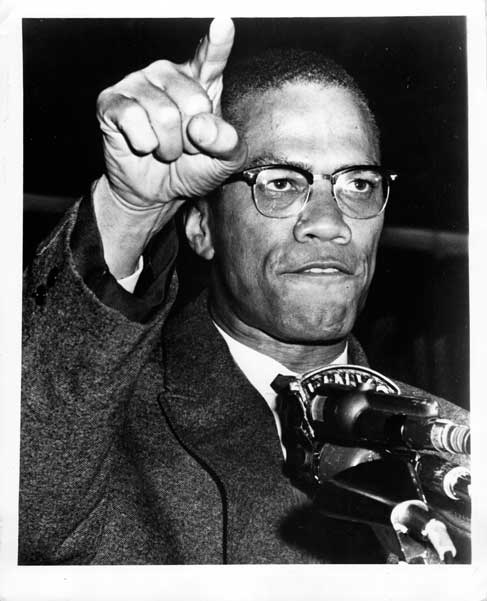

Civil rights activist Malcolm X (RNS file photo)

A famous exception to all those erasures comes in the early pages of Alex Haley’s landmark book “Roots,” in which he (partially) traced the Haley family back to a “forefather,” Kunta Kinte, one member of a large, prosperous Muslim family in Gambia, whose descendants thrive there today.

Haley is also the author of “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” whose narrator is that other major American Civil Rights leader — the northern, urban street fighter counterpart to southern, rural Martin Luther King Jr.

Malcolm: who changed his last name three times in 39 years, from Little to X to Shabazz, the one who had the nerve to declare in 1964 that accepting Islam had “solved my personal problem,” and who indicated that the faith might hold some good medicine for America’s racism, too.

The son of a preacher, Malcolm came a long way from his childhood Nebraska home, which Klansmen on horseback surrounded one evening waving torches. Not long afterward, his next home was burned to the ground. Two years later, his outspoken father was murdered by white supremacists. His grief-stricken mother was subsequently committed to an asylum.

Fire. Murder. Madness. Sound familiar?

As the George Floyd protests catch fire around the world, Malcolm X’s life story resonates globally. So do his core beliefs.

By his own testament, what healed the traumatized Malcolm’s deeply wounded spirit was an ethic that stripped the authority out of racism as a social force.

This ethic is stated throughout the Quran and forms the keystone of Muhammad’s final sermon to his people, but it could easily be the watchword of Martin Luther King, Jr’s entire civil rights struggle: “A white person has no superiority over a black, nor does a black have any superiority over white, except by reverence and right action.”

If put into practice, this prescription would end America’s peat fire problems for good.

That is what is being called for now: to strip racism away from our society and from our public institutions, to reacquaint ourselves with the real work of respecting, serving and protecting people.

You don’t have to be a Muslim to embrace this ethic. You just have to be a human being.