Chinese region has fewer mosques and shrines than at any time since the Cultural Revolution, says thinktank.

Thousands of mosques in Xinjiang have been damaged or destroyed in just three years, leaving fewer in the region than at any time since the Cultural Revolution, according to a report on Chinese oppression of Muslim minorities.

The revelations are contained in an expansive data project by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), which used satellite imagery and on-the-ground reporting to map the extensive and continuing construction of detention camps and destruction of cultural and religious sites in the north-western region.

The thinktank said the Chinese government claims that there were more than 24,000 mosques in Xinjiang and that it was committed to protecting and respecting religious beliefs were not supported by the findings and estimated that fewer than 15,000 mosques remained standing – with more than half of those damaged to some extent.

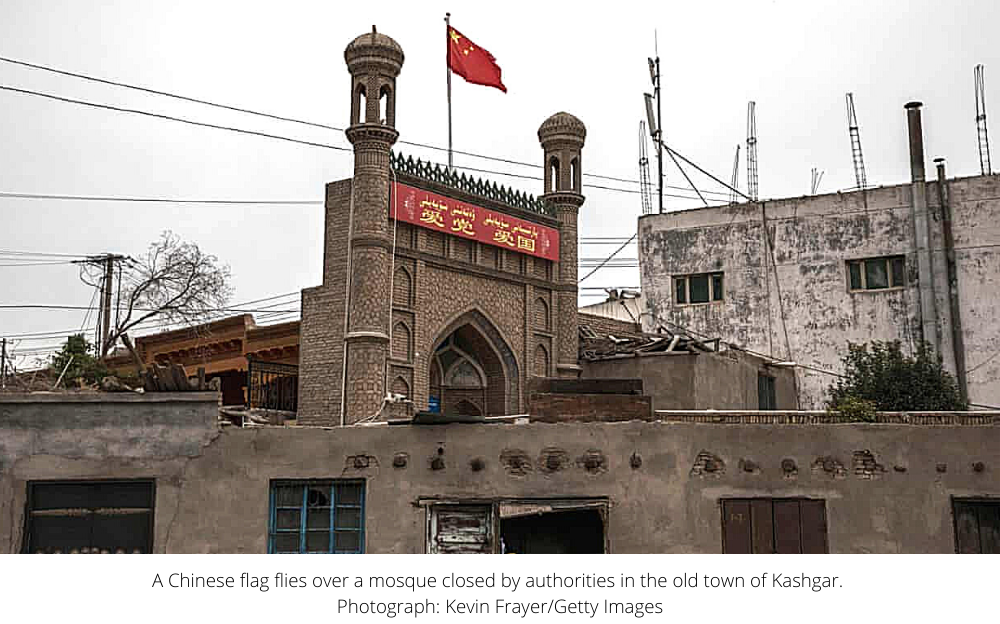

“This is the lowest number since the Cultural Revolution, when fewer than 3,000 mosques remained,” the report said. Since 2017, an estimated 30% of mosques had been demolished, and another 30% damaged in some way, including the removal of architectural features such as minarets or domes, the report said. While the majority of sites remained as empty lots, others were turned into roads and car parks or converted for agricultural use, the report said.

Some were razed to the ground and rebuilt at a fraction of their former size, including Kashgar’s Grand Mosque, built-in 1540 and granted the second-highest level of historic protection by Chinese authorities.

Areas that received large numbers of tourists, including the capital, Urumqi, and the city of Kashgar, were outliers, with little destruction recorded, but ASPI said reports from visitors to the cities suggested the majority of mosques were padlocked or had been converted to other uses.

ASPI said it compared recent satellite images with the precise coordinates of more than 900 officially registered religious sites which were recorded prior to the 2017 crackdown, then used sample-based methodology to make “statistically robust estimates” cross-referenced with census data.

Before and after satellite images of Kargilik Mosque in Xinjiang. Courtesy of Google Earth/Digital Globe; Courtesy of Planet Labs and Nick Waters/Bellingcat

Beijing has faced consistent accusations – backed by mounting evidence – of mass human rights abuses in Xinjiang, including the internment of more than a million Uighurs and Turkic Muslims in detention camps, the existence of which it initially denied before claiming they were training and re-education centres. The camps and other accusations of abuse, forced labour, forced sterilisation of women, mass surveillance and restrictions on religious and cultural beliefs have been labelled as cultural genocide by observers.

Beijing strenuously denies the accusations and says its policies in Xinjiang are to counter terrorism and religious extremism, and that its labour programmes are to alleviate poverty and are not forced.

The ASPI report said: “Alongside other coercive efforts to re-engineer Uighur social and cultural life by transforming or eliminating Uighurs’ language, music, homes and even diets, the Chinese government’s policies are actively erasing and altering key elements of their tangible cultural heritage.”

Interventions on minority ethnic cultures and communities have increased under the leadership of Xi Jinping. In recent weeks it was revealed authorities have also vastly expanded a forced labour programme in Tibet, and policies to reduce the use of the Mongolian language in Inner Mongolia. Government terminology frequently describes a need to transform the“backwards thinking” of the targeted cultural groups.