On a freezing-cold night in November, the UWM Union Fireside Lounge was the site of a panel discussion on the Arab Spring by four people whose expertise was both personal and professional.

The Arab Spring, a series of uprisings that took place all over the Middle East beginning in late 2010, is now widely seen as a failed experiment in democracy, since it did not result in an immediate end to dictatorship in the region. In fact, the violence that resulted was often deeply destabilizing. But those who attended the panel at UWM came away with a broader, and ultimately more hopeful, view.

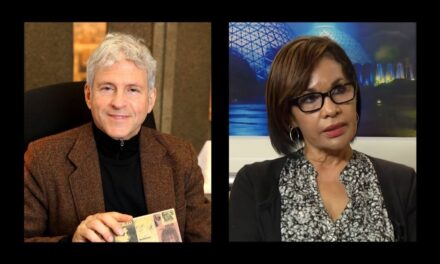

The panel, called “Arab Spring: A Psychosocial Perspective,” was occasioned by Dr. Omar Reda’s weeklong visit to Milwaukee for a series of workshops on healing refugee trauma and mental health in Islam.

The Arab Spring began in late 2010 in Tunisia. Perhaps its most famous manifestation was in Egypt, where a series of mass demonstrations in Cairo’s Tahrir Square succeeded in removing the corrupt autocratic Hosni Mubarek from power. Today, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, a former general, holds power in Egypt and corruption continues to run rampant. And in Yemen, Libya, and Syria, the wars and revolutions inspired by the Arab Spring have yet to be resolved.

Dr. Reda, a Portland, Oregon psychiatrist working in the Muslim community there, has paid many visits to refugee settlements on the Syrian-Turkish border and in Libya and Bangladesh. Born and raised in Libya, his firsthand experience of refugee trauma began in 1999 when Libyan strongman Muammar al-Gaddafi “decided that I should be thrown in jail because I was doing a little bit of humanitarian work.” Reda “took the first boat across the Mediterranean” and went to England to stay with an uncle. As an asylum seeker there, he was told by a judge that he didn’t meet the criteria because “there is no evidence of torture on your body.”

Dr. Reda has a gentle, easy-going manner and is fond of stories, which are often inflected by his wry sense of humor. Though he trained as an adult psychiatrist, he taught himself art therapy after witnessing the effect of trauma on children. “These children and survivors are the real heroes. I’m here today because I want to give them a voice. Unfortunately the invisible scars of war is something that we dismiss.”

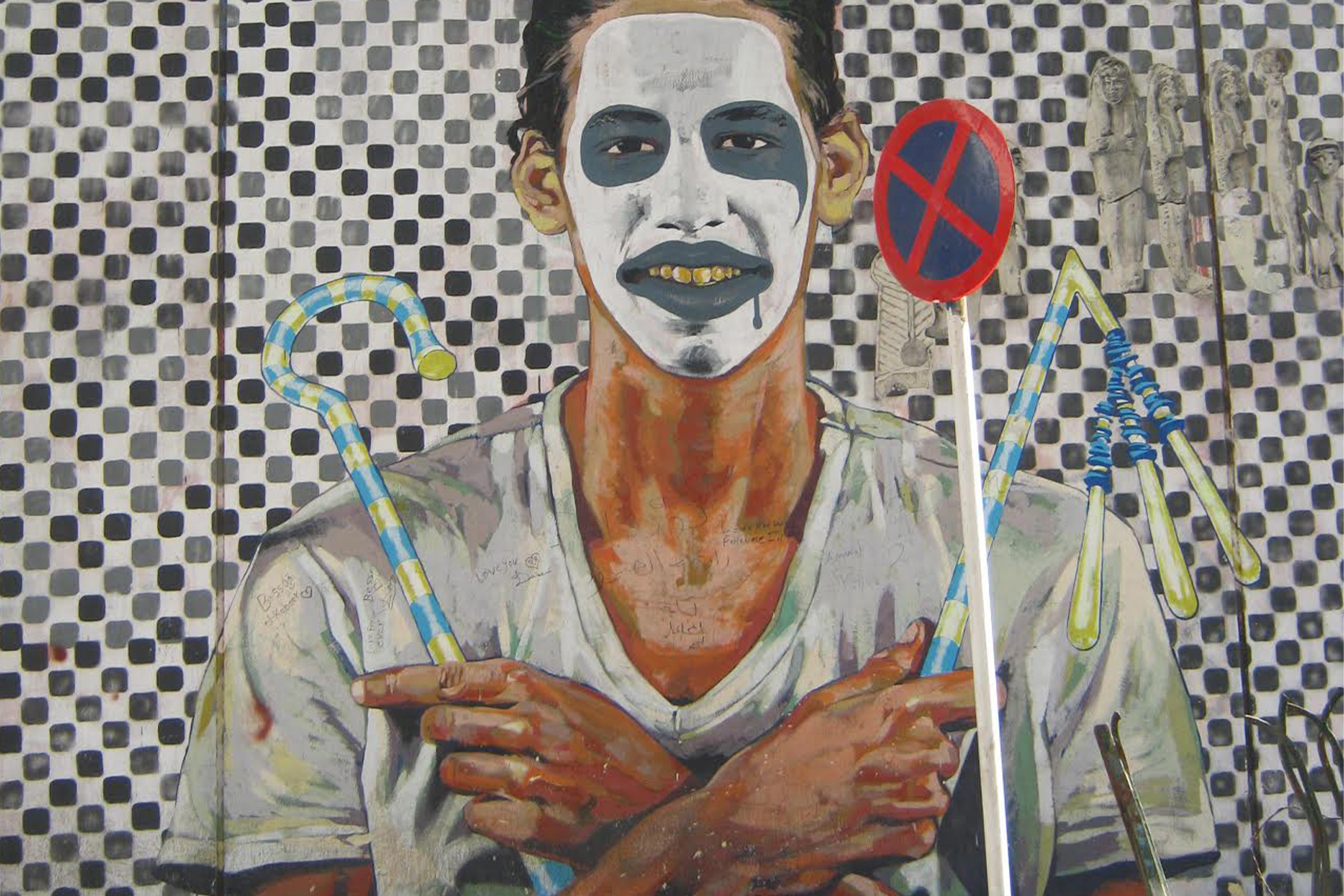

The next panelist, Professor Caroline Seymour-Jorn, Director of Global and International Studies at UWM, presented a series of slides from her forthcoming book, Creating Spaces of Hope:Young Artists and the New Imagination in Egypt. The artists she profiles in her book are “keyed into the psychological impact of everything that’s happened since January 2011,” she said.

Hany Rashed is an installation artist, sculptor, and painter who is considered Egypt’s “King of Pop Art,” said Seymour-Jorn. One of his works consists of “hundreds of pieces of plastic” melted and remolded to form the image of a couple riding on a motorcycle and “suggests the ways society distorts the way people really want to be,” said Seymour-Jorn. Bassem Yousry’s “Parliament of the Revolution” is a room “painted with satiric figures from the revolution that resulted in the ascent of the Muslim brotherhood,” and reveals both the viewer’s and the artist’s “complex wishes, desires, [and] needs,” including the need for freedom, Seymour-Jorn said.

“While these artists are exploring deathly serious topics, they do so in a way that is extraordinarily creative, innovative, sophisticated, and also in a way that often invokes humor as a way of dealing with the psychological traumas of oppression,” Seymour-Jorn said.

The next panelist, Mohamed Sandid, whose day job is IT manager, works as a volunteer with Somali, Burmese-Rohingya, and Iraqi refugees, helping them to resettle in Milwaukee. Originally from Tunisia, he travels there regularly to visit family and reminded the audience that that largely peaceful and successful revolution also began in trauma. Tarek el-Tayeb Bouazizi, a street vendor, “started the Arab Spring by self-immolation.”

Sandid explained that in 2010, “Tunisia was a police state.” And “a woman police officer insulted this man who was trying to make a living selling some fruits on a cart.” Bouazizi, whose photograph was part of Dr. Reda’s opening presentation, “was basically slapped around and his cart kicked because he didn’t have a permit, and he set himself on fire and started the Arab revolution,” Sandid said.

Ammar Abo Bakr’s, “Portrait of Hosham Rizq” from Caroline Seymour-Jorne’s presentation

The key to Tunisia’s democratization was its underlying stability and the fact that the army never intervened. Though the revolution was successful on a political level, Sandid said, “there’s a lot to be done on the socio-economic level . . . All these finances, all these riches, weren’t going to where they should go – [instead] they were going into some elite’s pockets.”

Returning to Tunisia, Sandid was surprised by the openness of the political discussions in barbershops and cafes. “Now we can say whatever we want on TV, and we can criticize people” but “that didn’t translate into economic welfare.”

However, Tunisia today has renewed cause for optimism. Last October, Kais Saied, a 61-year-old lawyer, was elected president with what Al Jazeera called a “groundswell” in the youth vote.

Sandid said the hallmark of the Saied candidacy was that “he didn’t spend any money. There was a joke going around that he won the election with ‘Two coffees and two croissants,’ basically because people liked what he had to offer, what he said,” including his promise to fight corruption. “There’s been a lot of depression among people,” Sandid said, “but now suddenly . . . the day after he got elected, thousands of youth went out in the streets [and] painted murals. People are now reclaiming their country.”

However, despite that renewed optimism, no one on the panel was willing to shirk the harsh realities unleashed by the Arab Spring. Another slide that Dr. Reda showed during his opening presentation was of a thirteen year-old Syrian boy named Hamza.

The fourth panelist, Fahed Masalkhi, who teaches in the Foreign Languages and Literature department at UWM, hails from Damascus, Syria. He told Hamza’s story in the context of questioning how one copes with the trauma inflicted on families when one of their own experiences the worst death imaginable.

Hamza was taken on April 24, 2011, more than a month after the uprising began in Syria, and to his parents on May 29 by the security forces who had taken the boy. His body had “three bullet holes, his feet were blackened from the torture that was administered to him, [there were] drill holes in his body, cigarette burns, and his genitals were gone,” Masalkhi said,

In Syria, said Masalkhi, “there are a lot of bad deaths,” including his own brother-in-law who was taken from his business in 2014. A gentle, soft-spoken man, Masalkhi’s adult son had said of uncle, ‘“You cannot meet a more apolitical person.’ We were puzzled, why would Abdul be taken. And we were afraid the experience would leave him traumatized.”

That fear proved short-lived. Masalkhi explained that in Syria “there are 17 security apparatuses, and they basically shovel people between them. It’s a money-making, money milking thing.” Despite the fact that Masalkhi’s family was “happy to pay” for his brother-in-law’s return, and in fact, did pay, they were told to “come and collect his corpse.” The funeral took place in the presence of a security officer and two soldiers, preventing the family from even properly mourning their dead loved one. “So how do you cope with a bad death?” Masalkhi asked. “This kind of trauma, how do you deal with it?”

Dr. Reda began his slide show with images of his own losses, a sister who had died of brain cancer when she was only 14, an adult nephew killed during the Libyan revolution, his mother who had recently died. He acknowledged that “reality is often very ugly.”

But he suggested a number of ways to help people cope, beginning with “the example of the beloved prophet.” Children, he said, “felt safe around him, they climbed on his shoulders. They had an adult caregiver that they could go to.” These are the models, he said, that he uses in working with children and adult trauma survivors.

“You can lean on your spirituality, whatever your belief system, you have to have hope, somebody you can go to,” he said. In addition to being a practicing clinician, Dr. Reda and his wife run programs for boys and girls that meet regularly. And in summer, they invite teen-agers and young adults to Camp Silah, where they can “connect to each other and to nature” and are required to leave their cell phones behind for four days. “If you give people hope,” he said, “they will not listen to that other voice,” the one that urges them to violence and destruction.

As for the Arab Spring, Fahed Masalkhi refused to be pessimistic despite the continued fighting in his homeland. “Syria was supposed to be the burial place of [the Arab Spring] and it is not,” he said. “Look at Beirut, look at Algeria, and look at Sudan and Tunisia. The Arab Spring is alive and well.”