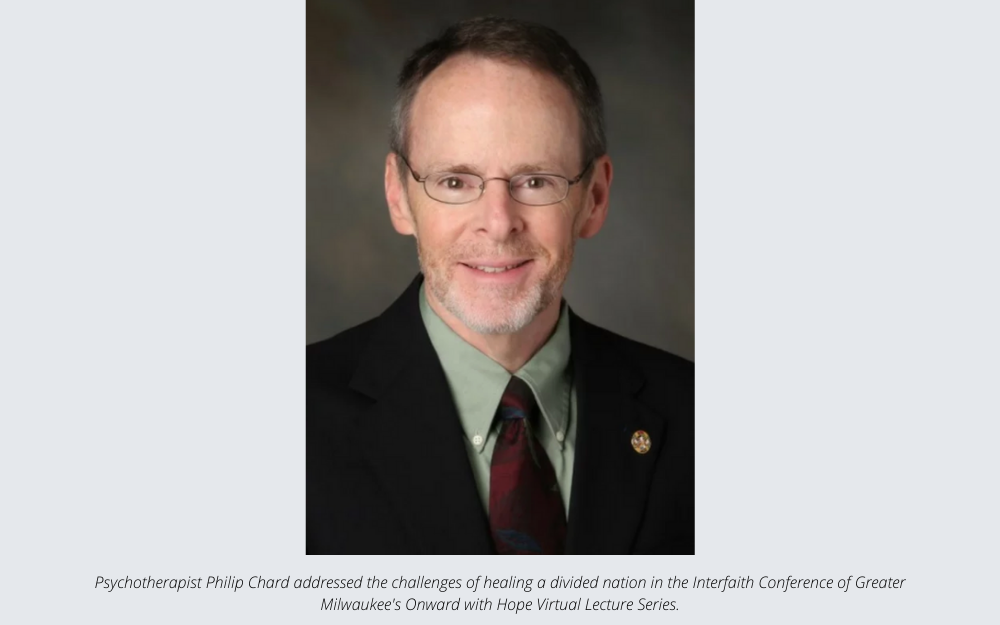

Photo ©:

Philip Chard & Interfaith Milwaukee

“What should we do when we are face to face with someone who sees the world very differently?” asked psychotherapist Philip Chard during the kick-off session to the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee’s annual Tuesdays-in-March series, which wraps up today. “How do we begin to close this very wide chasm we are experiencing? How do we find common ground? What can I do as an individual to further that process?”

Organized by the Interfaith Conference’s Peace and International Issues Committee, the series invited people to come together weekly in March to consider how to move forward beyond the pandemic and the nation’s deep political divides.

With the theme, Onward with Hope: Inspiring Courage to Create the World We Want, it took a proactive approach to tackling some of society’s most difficult challenges. Topics included healing political divisions, nurturing hope, addressing racial diversity and equity, understanding cultural dynamics around social and spiritual castes, and acknowledging the needs of those returning to their communities after incarceration.

“We have a rather sophisticated audience who are well versed on issues. We want to provide information that is really useful to them,” said Jeanne Mantsch, the current PIIC Chair.

“We are not only raising critical information, but also showing a path forward,” said Tom Heinen, Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee executive director emeritus.

Addressing the challenges of a divided nation

As the seven-member PIIC began exploring topics for 2021, Americans were experiencing angst created by the global pandemic and the nation’s political divides. “Coming off a very tough year, when people are isolated at home and frustrated by the political atmosphere around them, we needed ways to address these issues,” Heinen said.

Philip Chard’s presentation on how to connect across political divides launched the talks. Chard is a psychotherapist and author who, for over 34 years, wrote an award-winning weekly column in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel titled “Out of My Mind,” now published in the Shepherd Express.

Chard offered “a mix of psychology and neurology, rich with all the facts and sources, that gave the audience very clear steps on how to engage someone in conversation without triggering fears,” Heinen said. “Whether it is used across political divides, with Islamophobia, or in difficult family conversations, these steps would be useful.”

How can you believe that?

What makes people differ in their political views? About 53% of it is biology, Chard said.

People on the right and left, liberals and conservatives, differ in personality, moral values, cognitive processes (the way they think) and brain structures (brains look different and operate differently), Chard said. Research on the political mind has been available for more than 20 years that shows the differences between liberal and conservatives are not just psychological; they are also neurological.

Citing statistics from the Pew Research Center, Chard noted that the numbers of people who believe conspiracy theories is very high today:

- 24% believe the 2020 election was stolen for Biden; another 23% are not sure.

- 20% believe Antifa staged the Capitol insurrection; another 34% are not sure.

- 17% believe Satanic pedophiles control the government; another 37% are not sure.

- 12% believe mass shootings are staged events to try and implement severe gun control; another 17% are not sure.

“That’s pushing 50% who believe these theories are plausible,” Chard noted.

Science provides some explanations, he said. “People who are entrenched in conspiracy theories are driven by fear, which is partly driving this tremendous division in our country.

“They have very high levels of ambient fears (fears that are always there in the background). They are suspicious, even paranoid, driven by the fact that they feel powerless, left behind, marginalized.

“One of the ways they get back their sense of power and meaning is to attach themselves to some kind of group-think that makes them feel they understand what is happening. Identity becomes connected to group. That diminishes their fear.

“What they are really doing by subscribing to these beliefs is trying to manage their fear. Knowing that gives us an opening to have some compassion for these folks. Not an easy thing to do but an important thing.”

Science shows that certain people are more impressionable and have “high illusory pattern perception,” meaning they find connections where there are none, Chard said. They also have a high degree of confirmation bias. Once their brains see a pattern, the brain pays attention to things that reinforce their beliefs. Genetic and physical characteristics make this happen, he said. At the same time, social media and its algorithms accelerate their finding of patterns.

An external factor that impacts people’s thinking is political rhetoric, Chard said. If there is a disconnect between one’s values and actions, the person will experience “cognitive dissonance” that will make they uncomfortable.

“This factor is not lost on politicians. When politicians make stump speeches, they know they can’t create cognitive dissonance in the voter. So, what do they do? Politicians avoid details about policy positions that could potentially create cognitive dissonance and instead they emphasize other persuasive elements: tribalism, fear, hope, while avoiding details about policy positions.

For example, in the 2016 presidential campaign, Chard saw a beat-up truck in front of him with a Trump bumper sticker. Its owner appeared to be working class and Trump’s policies did not help the working class, but other factors must have persuaded the driver.

“How do you get people to vote against their own self-interest? Don’t talk about policy. Present soundbites, appeal to tribalism and say things that will arouse their fear.”

Connect with empathy

To persuade people, “the classic thought is to provide enough education and evidence, and people will change their mind. But that is not true. It doesn’t cause change,” said Heinen. “All we have to do is look at smoking to see that approach doesn’t work.”

“The way to turn people around is to reduce their sense of powerlessness,” Chard said. Show respect to the other person rather than just trying to win an argument, he said.

He offered the following, evidence-based steps:

- Hit the pause button on your own proselytizing. When people have the experience of someone really listening to them, they feel they have been heard and respected.

- After you listen, ask open-ended questions. How did you come to your conclusions? What is the source of the evidence? What will happen next? This is called, “motivational interviewing.” It encourages the other to think critically and shows interest in knowing what they think.

- Acknowledge what you are learning from them.

- Share your opinion – respectfully.

- Model doubt because that is what you want them to experience. “This discussion has gotten me to a place where I want to go back and check my facts.”

- Don’t debate. It creates the backfire effect and you may end up further apart than you were in the beginning.

Chard recommended flavoring these conversations with humor and storytelling. “When we laugh together, we feel connected. Stories are an express lane to the heart. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, it is hard to hate someone when you have heard his story.

“Empathy is the critical component and it has to be genuine. Absent that, you can forget about connection, the message is not going to get through.”