GREEN BAY, Wis. (AP) — Twenty years ago, as Muslim Americans joined others mourning the victims of the 9/11 attacks, they also faced the increased threat of Islamophobia.

The sentiment ranged from personal attacks on Muslims, and anyone who could be mistaken as Muslim, to words of bigotry. Harmful stereotyping and rhetoric alienated people as they lived and served in their communities.

Muslim Americans in Wisconsin say they’ve had to increase community conversations and political involvement, and advocate against Islamophobic policies and rhetoric. That extra civic engagement has emerged over the two decades since members of al-Qaida hijacked airliners and crashed them into the World Trade Center towers, the Pentagon and a field in Pennsylvania.

“I think that as a Muslim community we definitely have become much more aware and much more politically active and politically involved,” Janan Najeeb, president of Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition and founder of the Wisconsin Muslim Civic Alliance, said. “Because we realize if we don’t present our narratives, there are enough people out there that don’t like us that would prefer to create the narrative that they want.”

Fear became a dominant emotion in the immediate aftermath of the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. Americans everywhere worried about where and when the next strike might happen, whether their community could be a target. On top of those concerns, Muslim Americans worried about being scapegoated individually because of their faith and their appearance.

“Immediately post-9/11 was an incredibly scary time for Muslims,” Najeeb said. “Not only did we mourn for our country because we’re Americans, as well, but we found ourselves also a target. There was this broad-brush generalization.”

Islamic Society of Milwaukee Imam Ameer Hamza recalled many people being afraid, including in his own immigrant Muslim community, the Green Bay Press-Gazette reported.

“Right after 9/11, there were a lot of stories of people for instance cutting their beards, taking off their hijabs, shortening their names to Mo or Sal. … So those stories were hard and heavy,” Hamza recounted.

“There was sentiment among our Desi (South Asian) community just lay low and don’t put yourself out there too much. This was a constant, constant fear. For example, I was giving talks at the masjid (mosque) at that time as well. And my dad would tell me multiple times ‘No political (sermons) … ’ Very, very risk averse.”

The sentiment was especially strong for those in the older generation who had immigrated to America for prosperity and education and didn’t want to risk being mistaken and in trouble.

“There’s a large group of immigrants that thought that way: The storm will pass, let’s just lay low and bide our time and just suffer whatever persecutions are coming our way,” Hamza recalled.

However, other Muslims took a different approach. They set out to communicate who they were as neighbors and community members.

Ali Hamadeh, an engineer in Waukesha County who had immigrated in 2000, recalled engaging in conversations just to address any concerns or fears.

“I think it was more on a personal level, so just trying to talk to coworkers, neighbors, trying just to avoid stereotyping and trying to explain this is a fringe group. It is not representative of the wide, wide majority of people of the Islamic faith,” Hamadeh said.

Conversations happened at formal events, too, such as the annual Interfaith Gatherings in Oshkosh for nearly two decades, said Mamadou Coulibaly, president of the Fox Valley Islamic Society.

For many Muslim Americans, this increase in community outreach came with the recognition that they did not have to apologize for tragedy and violence they had nothing to do with, Najeeb said.

This increase in engagement has been especially strong in the last five years, not just among Muslim Americans but across many demographics, Najeeb said. She noted increased community involvement and political representation on school boards, common councils, as well as state- and national-level governments.

Muslim Americans are channeling a political voice, said Brother Will Perry, director of the Milwaukee Islamic Dawah Center and president of the Wisconsin Muslim Civic Alliance.

“The main thing is to raise the awareness for the Muslim community that we have a voice and we have some political power,” Perry said. “We have within our organization the potential to do a lot, have a significantly positive impact on the way politics is run and managed. And we bring that ethical component to the political arena.”

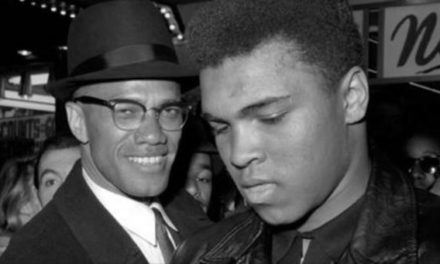

He noted that the children and grandchildren of immigrants are learning more about the Civil Rights Movement and aligning themselves with African American Muslims’ struggle during that period.

“Now we’re starting to see a collaboration and an understanding and an appreciation for what has been going on or that has taken place in the past with the Muslims that are African American here,” Perry said.

Najeeb believes that while Muslim Americans have faced increased Islamophobia these past two decades, leaders and activists have worked well with allies to advocate for human rights and dignity. With allies, their numbers grow as a collective voice for peace and education.

In more recent years, the ban on travelers from several predominantly Muslim countries under the previous administration concerned Muslim American activists and allies.

“I think that we were confident that the government was always looking out for our best interest, but I think the previous four years under Donald Trump was definitely a wake-up call, and we realized we could not sit on the sidelines,” Najeeb said. “But what was also very apparent was we have a lot of allies.”

Younger Muslim Americans are taking the reins for community engagement and political activism. This was seen especially this past summer, Najeeb and Hamza said, when young Muslim Americans organized protests after the murder of Minneapolis resident George Floyd.

“I’m very optimistic, especially as I see many of our young people being very dedicated to education, dedicated to social justice work, dedicated to doing things to improve the lives of people,” Najeeb said.