The story of the Central Park Jogger case is one of mass hysteria, incompetent police work, and trial-by-press. It is a story of racism and injustice. Five young black and brown men were imprisoned for a rape they didn’t commit, and a serial criminal was allowed to roam the streets of New York City. As a result, another woman was brutally raped and murdered with her children in the next room.

Before Yusef Salaam, one of the Central Park Five, took the stage at Madison College’s Mitby Theater on an unseasonably cold November night, the audience buzzed with excitement and anticipation.

Ava DuVernay’s “When They See Us,” has been playing on Netflix since May. Ken Burns’s documentary, “The Central Park Five” was released in 2012, ten years after the men were exonerated – not by the Innocence Project, not by police work, but by the unexpected jailhouse confession of convicted murderer Matias Reyes, whose DNA had been in the system almost the entire time.

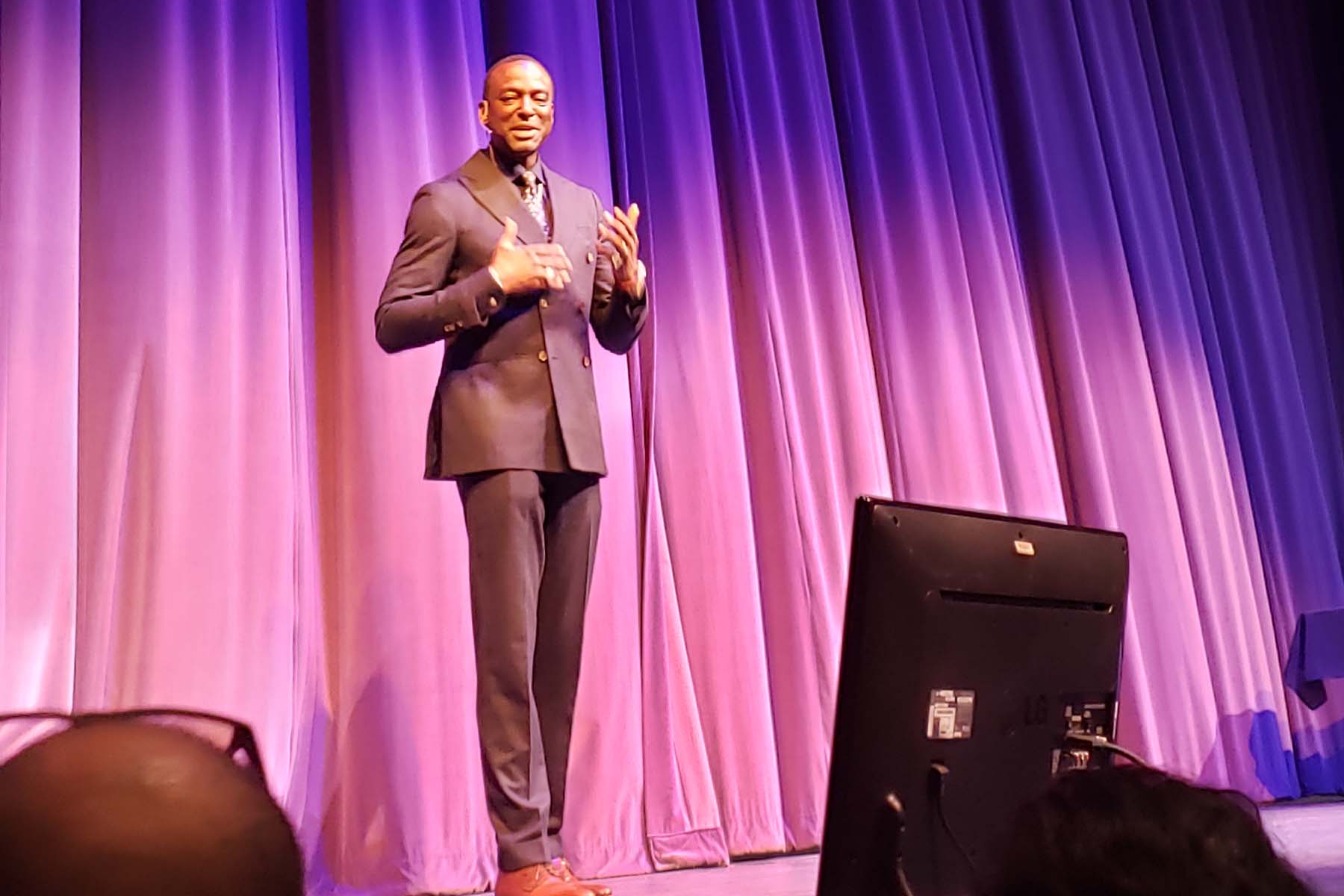

But when Yusef Salaam took the stage that night, he seemed to be entirely free of anger. Salaam’s version of the Five’s story is not simply the story of a man of courage overcoming obstacles, though he did that. It’s not even the story of how Salaam, a devoted Muslim, used his faith in God to overcome those obstacles.

“The Central Park Jogger story is a story of how the truth can never stay buried,” Salaam told the crowd at the Mitby Theater. “They forgot that we were seeds. We emerged like the Phoenix. As they built a fire to consume us, they forgot the power of the heat.”

Salaam, it turned out, is a man who used obstacles to grow closer to God.

Tall and imposing in an expensive suit with a gold medallion around his neck, Salaam, 45,likes to refer to himself as one of the “Exonerated Five.” He conveyed a message of gratitude and joy that caused his audience to frequently break into laughter. Yet he never backed away from the hard truth of what happened to him and the other four.

In 1989, the press referred to the boys, who mostly didn’t know each other, as a “wolfpack.” They were said to be out “wilding” on April 19, 1989, the night of the attack on Trisha Meili, 28, the jogger who was near death when she was found by two passersby in a Central Park ravine.

Paraded before the public by the police, Salaam said he asked himself, “Why were they looking at me with such hatred?”At his trial, “They asked me to stand if I had anything to say. At that very moment, as I stood, I saw what they were looking at. I began to rise and they began to shrink,” he said. He told the courtroom, “This case is not a case. It is a constructed sham.”

Salaam “had been branded a rapist. People in prison who beat up an old woman and took her purse were seen as more valuable than what I was accused of.” And New York City made its hatred and disdain personal. The New York Post ran a poem Salaam wrote when he was 12 under the headline, “Salaam Baloney.”

People in New York and across the nation thought they knew who these five boys were. Even their families were criticized for supporting them, for failing to admit the “truth.” What all of those people didn’t know, Salaam said, was “the future. Man plans and God plans and God is the best of planners.”

Five boys from Harlem were taken from their families and “put in the belly of the beast,” Salaam said. But even that place provided unexpected support to him.“Six months into my bit, an officer said to me, ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘I’m Yusef Salaam, one of the guys they accused of raping the Central Park Jogger, but I didn’t do it.’ To my surprise [the officer] said, ‘I know you didn’t do it. But who are you?’”

This question, Salaam said, “changed the whole trajectory of my life.” Salaam came from a Muslim family. DuVernay depicts Salaam’s mother in the courtroom at his trial, holding her Quran to her heart. But it wasn’t until after his conviction that he began to read the Quran. There he found the story of Yusef, a man of parts who is imprisoned for a rape he didn’t commit. And who is exonerated.

“When they looked at me with such hatred in their eyes, they were trying to get me to accept their hatred of me,” Salaam said. But his mother told him, “Stop talking to them. They need you to participate in what they’re trying to do. Do not participate.”

Except for Korey Wise, who was 16, the boys were initially placed in juvenile detention. When Salaam was 21, “They cut my flattop” his then signature look, and sent him to Clinton Dannemora, “one of the worst prisons in America.”

After Salaam arrived at Dannemora, two men approached him in the yard. Salaam related how he was “walking strong” when they took him to a corner of the yard where a prisoner was “beating up a bag” and said, “We found him.”

It was a scary moment. But to Salaam’s surprise, the man said, “We are members of the Black Panther Party. You are a political prisoner. If anybody messes with you, we will shut this place down.”

“I had to hold onto the rope God gave me,” Salaam said. “Every place that I was in, I was protected.”Even the officers with “the tattoos of black and brown babies with nooses around their necks” didn’t mess with him because they knew he had “a whole army at his back.”

Salaam’s emphasis on the kindness he received in prison is one of the most remarkable aspects of his story. A female officer left orange juice and Entenmann’s cookies in his cell at Dannemora. Salaam asked her why. “I know you don’t belong here,” she said, but “I can’t take the key and let you out.” Instead she left cookies and OJ.

Salaam earned a college degree in prison, but as an intelligent young man from a solid family, he would probably have done that anyway. When the Ken Burns documentary came out in 2012, Salaam said he was “hiding in plain sight” as a computer engineer at New York Presbyterian Hospital. On an elevator, one of the “wise women from the cafeteria” told him, “‘You make us proud. I hope you win your lawsuit.’ It was such a blessing to feel that from her,” Salaam said. It taught him that “when you are restored in society, psychologically and socially, you add value.”

In 2014, twelve years after being exonerated, the Central Park Five were awarded $44 million in their lawsuit against the City of New York.

But that is not something Salaam dwells on in his talk. It’s not the point. “We have to constantly be in a state of I AM,” he said. “Anything you say after ‘I am,’ you give birth to.”He reminded the audience that his story is also “not about white people fighting black people. They want you to think that. But the true fight is a spiritual one. This is to let you know that your heart will be at ease. Turn back to God. Put God in your life.”

Salaam was in Madison as part of the Madison College Talks series, which next semester will present Black Panther Bobby Seal. Today Salaam is a motivational speaker and author and the father of ten children. He told the audience he is working on a rap album.