Photo credit: Maryam Ahmed and Maria Ahmad

Mental health clinician AbdulAziz Syed (left) tells parents, “To help your kids, start with your own mental health.” Also on the panel at the Muslim Mental Health Matters event are Rama Shoukfeh (center) and Maryam Ahmed (right).

High school and college students face an epidemic of anxiety that the National Education Association called “the mental-health tsunami of their generation.” A 2019 Pew survey found that 70 percent of teens say anxiety and depression is a “major problem among their peers,” and that was before the pandemic.

U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy issued an advisory in December highlighting the urgent need to address the nation’s youth mental health crisis.

“Even before the pandemic, an alarming number of young people struggled with feelings of helplessness, depression and thoughts of suicide,” Surgeon General Murthy stated in the advisory. “The COVID-19 pandemic further altered their experiences at home, school and in the community, and the effect on their mental health has been devastating.”

Left unmanaged, it can lead to depression, other mental and physical disorders, substance abuse and even suicide, mental health professionals say. Suicide is now the second-leading cause of death among children and young adults aged 10 to 24, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

What’s a parent to do?

“Step one is for us adults to take care of our own mental fitness,” mental health clinician AbdulAziz Syed said Sunday to 35 participants attending Muslim Mental Health Matters at the Madison Public Library. The program was sponsored by the Madison Public Library Foundation. Syed is a licensed clinical social worker and therapist from the Khalil Center, a psychological and spiritual community wellness center in Chicago dedicated to advancing the professional practice of psychology rooted in Islamic principles.

The program was organized by three Madison women who submitted a winning proposal to the Library Takeover Initiative, which provides grant funding for Madison residents to host a program at the Madison Public Library. Dania Shoukfeh, a special education teacher; Maryam Ahmed, a master’s student in clinical mental health counseling; and Kelly Saran, a producer at PBS Wisconsin planned the program and invited Syed to be the keynote speaker.

Talking about Muslim mental health in Madison

Photo credit:

Madison Public Library hosted “Muslim Mental Health Matters.”

In an interview after the event, Shoukfeh said while the program was open to all ages, it turned out participants were primarily parents who wanted to know how to support their children.

“It turned into a coaching session for parents. They were all very engaged, asked lots of questions and stayed the whole time,” she said. “I hope we can do more programs like this in the future.”

Tareq Saddiq, a Madison father of two young adults, said he “learned how much we as Muslims are impacted by mental and physical health issues. It’s not just the non-Muslims.” The event also showed him other people are potentially dealing with the same problems, he said. “The speaker had ideas and suggestions we can use, and he taught us how to put ourselves in our kids’ shoes.”

Asime Ibraimi, 18, is from the small town of Lodi, about 30 minutes from Madison, where hers is the only Muslim family. The liberal arts student at Madison Area Technical College was one of a handful of youth to attend.

“As a Muslim myself, having a Muslim mental health professional speak was important,” Ibraimi said. “I felt inspired to have open communication within my family. It is good for mental health and important in our religion.”

Prevention instead of intervention

Photo credit: Maryam Ahmed and Maria Ahmad

Mental health clinician AbdulAziz Syed led participants in exericses to improve their own mental fitness.

“Parents say we need to do more programming for the youth,” Syed said in an interview last week with the Wisconsin Muslim Journal. “I get that. But if we were to talk about it holistically, we adults need to do a better job of how we interact with our children on a day-to-day basis. We don’t hear it often enough.”

As part of his job, Syed works in schools several days a week. “I see a lot of children and what are they talking about? Their parents. Their families. Their community. Their schools. For the most part, they are talking about the adults in their lives and how the adults are showing up or not.”

For example, many parents worry about all the time their kids spend on phones or video games, he said. “A bigger problem is the parents who are on their phones and kids who are growing up in a generation with parents who are disengaged. That’s a lot more damaging than the child being disengaged.

Syed referenced an article in the New York Times that discussed the 2013 book The Big Disconnect: Protecting Childhood and Family Relationships in the Digital Age. The primary author, Harvard Medical School clinical psychologist Catherine Steiner-Adair, wrote: “We spend the expanse of our days gazing into our phones, scanning for the next text, email or tweet. The message we communicate to our kids is: ‘Everybody else matters more than you.’ Children are tired of being the ‘call waiting’ in their parents’ lives.”

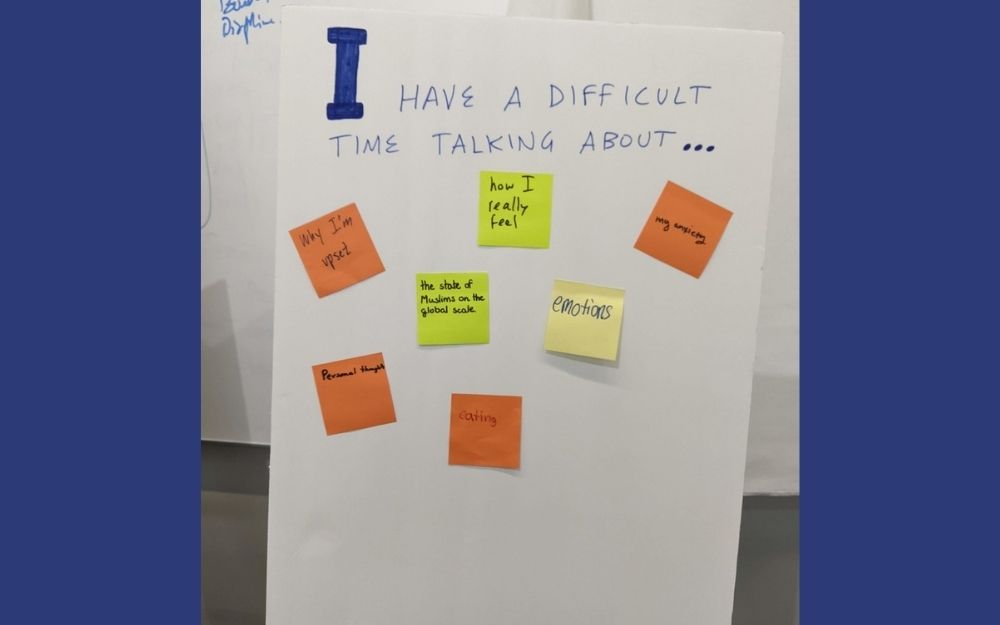

How mentally fit are you?

Photo credit: Maryam Ahmed and Maria Ahmad

“Ask yourself: How can I manage myself well? How can I manage my child well? Then do what you need to do. If that means therapy because you have some challenges, you have some trauma that hasn’t healed, that’s a good place to start.

“When it comes to our physical health, what comes to mind? Exercise, yoga, healthy food—the things we need to be physically fit. We need to think about mental fitness in the same way,” he said. “Like with our physical health, there is something in our control that we can change to improve our mental health.

“If I am exploding in the household, maybe there is friction in the marriage or problems at work, and it is being taken out on the children. Is there something wrong with my marriage? Am I unsatisfied with my job? Having a place where you can figure that out with either a close friend or a therapist would be valuable. Talk to someone you trust, someone you know will listen and not necessarily give you a quick fix answer.”

Islam and mental healthcare

Taking care of our mental health is part of the Islamic tradition, Syed said. Muslim scholars were writing about modern cognitive behavioral therapy way back in the Islamic Golden Age, he said. In “Sustenance of the Body and Soul,” 9th Century Islamic scholar Abu Zayd al-Balkhi discussed phobias and outlined a specific management plan.

“Access to counselors and clinicians culturally in tune with Islamic culture and faith may be difficult to find in Madison, but that doesn’t mean non-Muslim clinicians cannot be helpful,” Syed said. “Just be mindful that you are comfortable with your therapist.”

Therapists often consult with other mental health professionals to expand their knowledge and the Khalil Center welcomes therapists to consult with them, he added. It specializes in Traditional Islamically Integrated Psychotherapy (TIIP), a framework for psychotherapy that integrates contemporary behavioral science into an Islamic framework inspired by the Qu’ran, Prophetic tradition and traditions of the scholars.

Building parenting skills

Photo credit: Madison Public Library

Madison Public Library displayed an assortment of books for parents and teens at “Muslim Mental Health Matters,” a community event held at the library.

On the other hand, maybe what you need are skills, Syed suggested. “Start with building good listening skills. There is a lot of great content out there about listening skills, videos on YouTube and articles online.

“Maybe you want to start a support group for moms or for dads or for parents in your community. If you’re struggling, others probably are, too.”

Syed recommends a classic parenting book, How to Talk so Kids will Listen and How to Listen so Kids will Talk by Adele Faber and Elaine Mazlish. “Sometimes improving communication is just a matter of learning a new technique,” he said.

“We don’t have all the answers for the issues kids face but we can help find them,” Syed said. “We can help them walk through the situations they face rather than leaving them solo.”