On an unseasonably cold and snowy Halloween night, Boswell books on Milwaukee’s East Side was the site of a reunion – between an author and her subject, but also between two women of different backgrounds who had become close friends.

Cynthia Anderson was in town to promote her book Home Now: How 6000 Refugees Transformed an American Town. Joining her was Jamilo Maalim, one of five people whose stories ground the book.

Home Now is set in the former textile mill town of Lewiston Main, population 36,000. About 6,000 of Lewiston’s current residents are refugees and asylum seekers from eight African countries, many of them Muslim. According to Anderson, Lewiston now has one of the highest per capita Muslim populations in the U.S. Jamilo Maalim, whose husband Mohammed and children Alia, 7, and Hamsa, 4, accompanied her to the event at Boswell Books, came to the United States when she was 13 to escape the Somali civil war.

The evening began with Anderson reading a section of her book that explains her own connection to Lewiston and the situation of its “New Mainers.” Anderson was born and raised in Maine and as a child often traveled to Lewiston to shop on Lisbon Street, which she then considered “the center of the world.”

But Lewiston’s decline, while not yet obvious, had already begun.The textile mills that were the town’s largest employers were closing and jobs were scarce. In the 1990s, there was what Anderson called a “tenuous renaissance” with healthcare and banking providing some new jobs, but “half of families with children under 5 lived below the poverty line.”

Then, the Somalis began to move in, Anderson said, moving to the extreme northeastern United States by choice. Now, when visiting Lewiston, she began to see “women in hijabs shepherding kids down streets that had once been empty” and “Somalis stocking shelves in the supermarket, black and white kids sitting together at the library, and white people buying goat meat.” However, Anderson admits there has also been a hostile undercurrent, including an incident where a man rolled a pigpen through the door of a mosque.

Maalim was able to explain some of the reasons that people from a hot African country move to a place known for its harsh winters. Her first placement in the U.S. was in Dallas, Texas where, she said, things were “difficult, really bad for me and my family.” Maalim, who had never even heard of 9/11, found herself being blamed for it. “I got beat up for wearing hijab” and someone poured salt in her hair. “I felt like we were trapped,” she said. “At the time, [Texas] wasn’t a safe place for anyone who was black or African or Muslim.”

Then someone told her about Lewiston. Anderson, who has been writing about “Lewiston’s transformation” for more than ten years, believes that “in Lewiston things have mostly gone well” though the city has continued to struggle financially, and “joblessness is high among the older generation of refugees,” among whom, Anderson said,“the long-term effects of trauma linger.”

When Maalim and her family fled Somalia, they first moved to the Debaab refugee camp in Kenya. The largest refugee camp in the world, with a population of 450,000, it was founded in 2011 to house refugees from Somalia’s long-running civil war. Maalim’s mother still lives there, in a place where it is “not always safe.”Maalim, who is now a U.S. citizen, recently returned from Kenya to visit her mother, and said, “You have your hands on your heart because you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Separated from her mother by the war at an early age, Maalim said, “When I was young, I didn’t have a mother. The first time I met my mother, I was able to taste he food, and it made me feel at home.” She is trying to bring her mother to the U.S. but finds herself “stymied at every turn” by the Trump administration’s ever-increasing demands for documentation. Maalim herself never had a birth certificate. “I was born in a war. Who had time to write it down?” she said.

Maalim’s mother currently has no passport. And under the Trump administration, the number of refugees allowed into the United States was recently dropped to 18,000 per year. Anderson said this number is “one-tenth of what it was at the height of the Obama administration.”

When Maalim recently saw a Somali man at a Trump rally, she said to herself, “What is wrong with this son of Adam?” She said the day Trump got elected, she almost got run over by a car.

“I don’t think most of Lewiston’s newcomers voted for Trump,” Anderson said. “But some did. People are complicated.” She also said that “there is some vociferous opposition to new immigrants” in Maine, but that it’s “primarily where immigrants don’t live.”

While Maalim admitted that in the United States, she has “gone through a lot for being a Muslim, being black” she says she would never return to Africa to live. “To be honest, if I get my family here, there’s no way I’m going back” to Somalia or Kenya.

Part of the reason for that may be what Anderson said is the new emphasis on “acculturation, not assimilation among educators and community leaders” who now understand that “kids do best when close to their own cultures.” Today, Anderson said, “the richness of having two cultures” allows you to “forge your identity.”

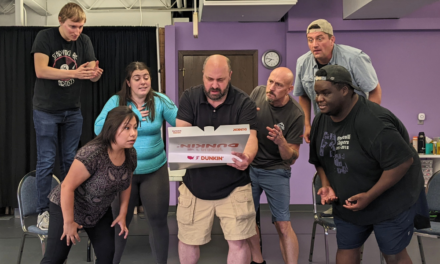

Maalim and her family recently moved to Milwaukee, where her aunt’s husband owns the Garden of Eden grocery store on Historic Mitchell Street. “I like it here,” she said. In the meantime, the vibrant and funny Maalim has maintained her friendship with the serious and empathic Anderson.When Mary Flynn of Lutheran Social Services, which sponsored Anderson’s visit, suggested the two women do a podcast together, Maalim joked, “Me and her, we could rock the world.”