Muslims gather in midday prayer on Sunday, Oct. 27, 2019, along the U.S.-Mexico border in Tijuana. RNS photo by Alejandra Molina.

Mustafa Dustin Craun wants to create a conversation around family, place and belonging, asking: ‘If you could design a prayer rug that reflects the place that you live, what would that look like?’

A Muslim convert, Mustafa Dustin Craun cherishes a brown prayer rug he bought on his first Umrah pilgrimage to the sacred site of Mecca more than 15 years ago.

Unlike the Hajj, the mandatory pilgrimage to Mecca, Umrah is a voluntary spiritual journey, which Craun performed in 2007. While in Saudi Arabia, he ventured to Medina, where the Prophet Muhammad is buried and where Craun found his prayer mat. It has been with him everywhere he has moved since — Mexico, Ghana, Morocco and San Diego, California, where Craun has been working on a documentary about a Muslim group he helped found, known as Border Mosque, that met at the U.S.-Mexico border to pray alongside a nonsectarian Christian ministry.

Craun has organized places for Muslims to pray during the Occupy Oakland demonstrations in 2011 and at other protests throughout California, and in 2020 he launched the nonprofit Center for Global Muslim Life.

To Craun, “there’s a profound impact on us praying collectively in public and making prayer a public conversation,” he said.

Now, Craun is spearheading the Global Prayer Rug Project, an international competition and local initiative aimed at showcasing innovative prayer rug designs from the U.S. and around the world.

Mustafa Dustin Craun. Video screen grab

An Islamic prayer mat’s basic function is cleanliness. Muslims are supposed to pray five times a day — at dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset and evening — and they can’t always choose the ground on which they pray. Prayer rugs are not just physical manifestations of devotion; they also carry stories of “love, loss, triumph and tragedy,” Craun explained.

“They are the living artifacts of our families, our histories and our homes,” he said.

The prayer rug project is seeking designers who could engage in listening campaigns in California and the Pacific Northwest to gather ideas for patterns and materials that could be used in making mats representing these two regions. The goal is to include the cultures and histories of the regions’ Indigenous and Muslim communities, and eventually incorporating this process in other U.S. cities.

An Islam in the Americas prayer rug will also be in the works, highlighting the fast-growing Latino Muslim population. A Global Refugee Prayer Rug competition will recruit refugee designers and youth from around the world.

Craun wants to create a conversation around family, place, and belonging, asking, “If you could design a prayer rug that reflects the place that you live, what would that look like?”

It’s an effort to address Muslim wellness, particularly as Muslim women, younger Muslims, Latino and African American converts may not feel completely accepted in older Islamic institutions that don’t always “take our community’s hyperdiversity seriously,” Craun said.

Such institutions and mosques export architecture styles from parts of the Arab world and India, where gender segregation is more pronounced, than at mosques in Southeast Asia or parts of Africa, according to Craun.

The Canadian Prayer Rug, a project of the Islamic Family and Social Services Association in Edmonton, Alberta. Photo by Sanjit Bakshi/IFSSA

The project is inspired by the Canadian Prayer Rug, an undertaking of young Muslims from the Islamic Family and Social Services Association in Edmonton, Alberta, who interviewed local Muslims and Indigenous elders to gather stories to inform the carpet’s design. The resulting rug is made of wool from sheep raised on the prairies of Alberta and dyed with juniper berries and other plants native to Central Canada. A social enterprise based in Pakistan helped produce a version of the rug that could be purchased.

The rug prominently features a lodgepole pine — the provincial tree of Alberta — that echoes the cypress trees found on traditional Syrian prayer rugs while paying homage to Canada’s Indigenous people, who used pines to support their buildings.

The rug’s background, in hues of blue, green, yellow and orange, shifts in color depending on the viewer’s perspective, reflecting the intensity of Canada’s winter and summer seasons.

Two crescents in the rug’s top corners pay homage to Al Rashid, the first mosque in Canada, located in Edmonton. An archway bordering the tree is also a nod to the architectural design of the Al Rashid mosque, which was dedicated in 1938.

Canadian Muslims are often “otherized,” said Omar Yaqub, with the Islamic Family and Social Services Association, even as they have made their homes on Canada’s prairies for more than a century. Yaqub said he has friends whose great-great-grandparents were Muslim. The use of local imagery and materials in the Canadian Prayer Rug emphasizes these roots, just as prayer rugs in Africa or the Middle East reflect the local residents’ identification with their landscapes.

Yaqub said he hopes to see more communities create their own prayer rugs, which he likened to “the act of making a home.”

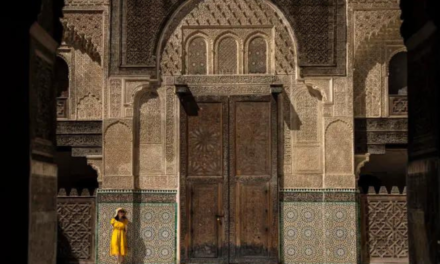

Prayer carpets in mosques generally have a row of arches. (AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki)

Craun said the prayer rug idea also came from the work his wife, Amor, was doing south of their San Diego home to provide halal meals to Muslim migrants seeking refuge in the U.S.

Through that advocacy, Amor Craun, who is from the Mexican state of Michoacán and migrated in 2013, learned that many of the Muslim migrants, who hailed from Sudan, Senegal, Afghanistan and even Russia, were in need of mats to fulfill their daily prayers.

She started distributing prayer mats that she acquired from a local store in El Cajon. As migrants received their mats, “their eyes got tearful,” she said.

Raised Catholic in Mexico, Amor Craun converted to Islam in 2015 after having explored other forms of Christianity, Buddhism and other faiths.

She said the prayer rug project is a way to show that “Muslims are also here … We are part of the Mexican society at large. We belong here, and this is a way to show the community that we’re here and that we recognize also the (Indigenous) people of the land as well,” she said.