Tiara, Cartier London, special order, 1936. Platinum, diamonds, turquoise. Sold to The Honorable Robert Henry Brand. Cartier Collection. Vincent Wulveryck, Collection Cartier © Cartier

For 175 years, the word “Cartier” has been synonymous with iconic French glamour, from massive diamonds to carefully considered watches. But part of the jeweler’s signature style wasn’t homegrown—it was inspired by intricate Islamic art.

Now, a new exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) explores how Islamic art influenced the French luxury jewelry house and helped Cartier become a household name around the world. Created by the DMA and the Museé des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, along with Cartier, the “Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity” exhibition is on view now through September 18.

The house’s love affair with Islamic art began at the turn of the 20th century, when Middle Eastern artists and merchants began bringing their art and antiques to exhibitions in major European cities. Louis J. Cartier, whose grandfather Jacques Cartier had founded the French family’s jewelry business in 1847, attended those shows and became fascinated with the patterns, shapes, colors and structure of Islamic art. His brother Jacques Cartier developed a similar connection to the distinct artistic style after traveling to India in the winter of 1911-12.

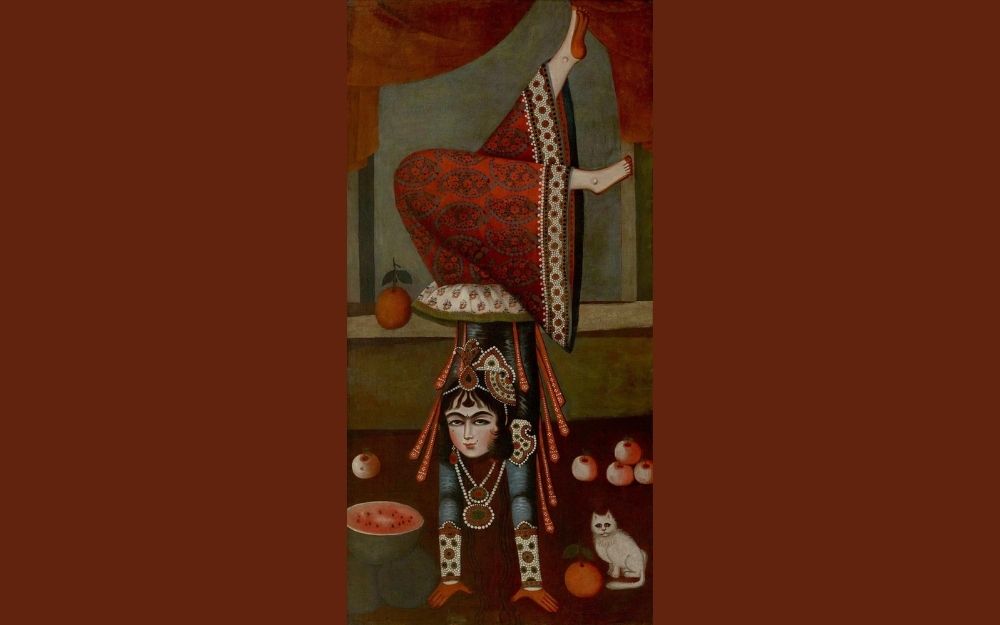

Female tumbler, Iran, early 19th century, The Hossein Afshar Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. © The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Photographer: Will Michels

As they expanded the family business around the world, the brothers began weaving Islamic art forms and techniques into their bracelets, watches, brooches, necklaces, rings, clocks and other high-end pieces.

More than 400 objects—from glittering tiaras to historical photographs and works of Islamic art from the DMA’s robust collection—tell the story of Cartier’s style evolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Cartier brothers—Louis, Jacques and Pierre—drew inspiration from India, Iran, North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula and beyond to develop the brand’s signature style, which evolved from Neoclassicism to Art Nouveau to Art Deco. Their colorful Tutti Frutti line of the 1920s and ‘30s, for instance, incorporated rubies, emeralds and sapphires in the shapes of flowers, berries and leaves found in traditional Mughal Indian jewelry.

“The discovery of Islamic art was so new,” Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s director of image, heritage, and style, tells Women’s Wear Daily’s Holly Haber. “It was an enchantment of new shapes that were very decorative and very different from what was in the environment.”

Ewer, late 10th-early 11th century, rock crystal, with enameled gold repairs and fittings by Jean-Valentin Morel (1794-1860), French, The Keir Collection of Islamic Art on loan to the Dallas Museum of Art, K.1.2014.1.A-B. Courtesy of Dallas Museum of Art

The exhibition also incorporates modern digital technologies, including extreme magnification and animated videos, to help show the creative process and the intricacy of Cartier’s pieces. A mechanical “breathing necklace” also shows how a 1948 gold and diamond piece morphs to conform to the neck. As Jean Scheidnes writes for Texas Monthly, the exhibition’s use of technology “empowers the jewelry by making its intricate beauty more legible.”

Cartier’s most famous piece of jewelry is the setting for the 45.52-carat blue Hope Diamond, which was mined in the late 17th century in what was then the Islamic Golconda Kingdom. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who brought the diamond back to France, traveled back and forth to Persia and India multiple times during his lifetime. His accounts of the Islamic world both fascinated the French and were used to justify colonial expansion into north Africa and India.

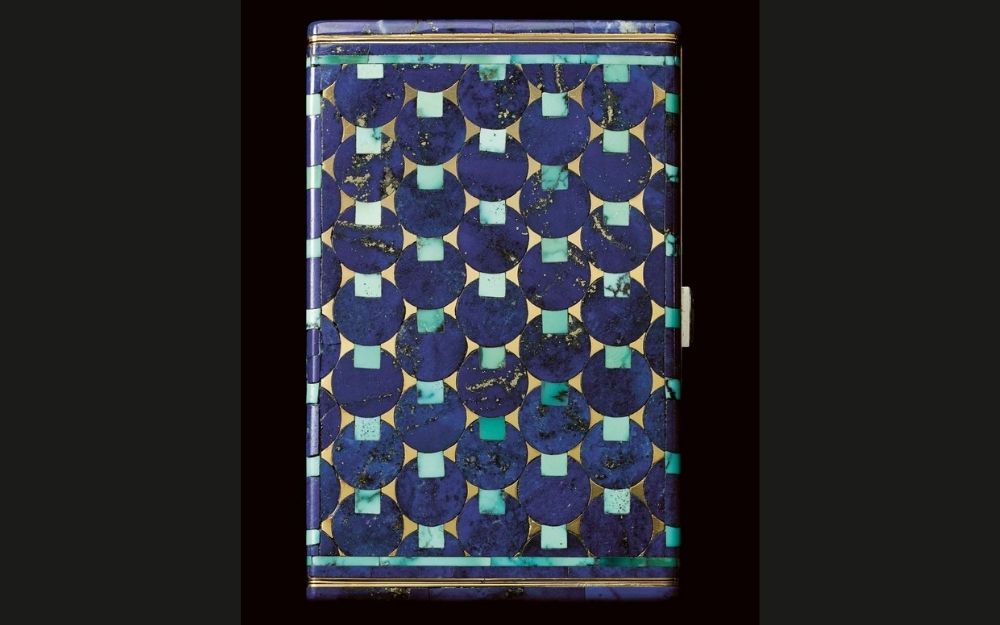

Cigarette case, Cartier Paris, 1930. Gold, lapis lazuli, turquoise, diamond. Cartier Collection. Vincent Wulveryck, Cartier Collection © Cartier

Though an exhibition focused on ultra-opulent jewelry that few people can afford isn’t likely to change the world or ease geopolitical tensions between East and West, as Islamic art expert Sabiha Al Khemir told Smithsonian’s Amy Crawford in 2010, museums can help bridge the gap between different cultures.

Islamic art, in particular—and the jewelry inspired by it—”is calling you to come close and look, to accept that it is different and try to understand that even though it’s small, it might have something to say. Maybe it’s whispering. Maybe you need to get closer,” Al Khemir said.

“Cartier and Islamic Art: In Search of Modernity” is on view at the Dallas Museum of Art, through September 18.

Sarah Kuta

Sarah Kuta is a writer and editor based in Longmont, Colorado. She covers history, science, travel, food and beverage, sustainability, economics and other topics.