On May 8, a young woman named Paula Hincapie was driving her five-year-old daughter to school in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood when she was pulled over and surrounded by Immigration and Customs agents from the Department of Homeland Security. The ICE agents told her they had been looking for her and that she was about to be taken into custody. They demanded to be taken to her home so that her daughter could be placed in someone’s care.

Paula Hincapie lived with her parents, Carlos Hincapie and Pastor Betty Rendón. Both were refugees from Columbia who fled to the U.S. in 2004, during that country’s bloody war between Colombian government forces backed by right-wing paramilitaries and leftist guerillas. Rendón had been principal of a school in Colombia and was threatened by guerrillas when she refused to allow them to recruit her students.

The couple’s asylum claims were denied in 2009.

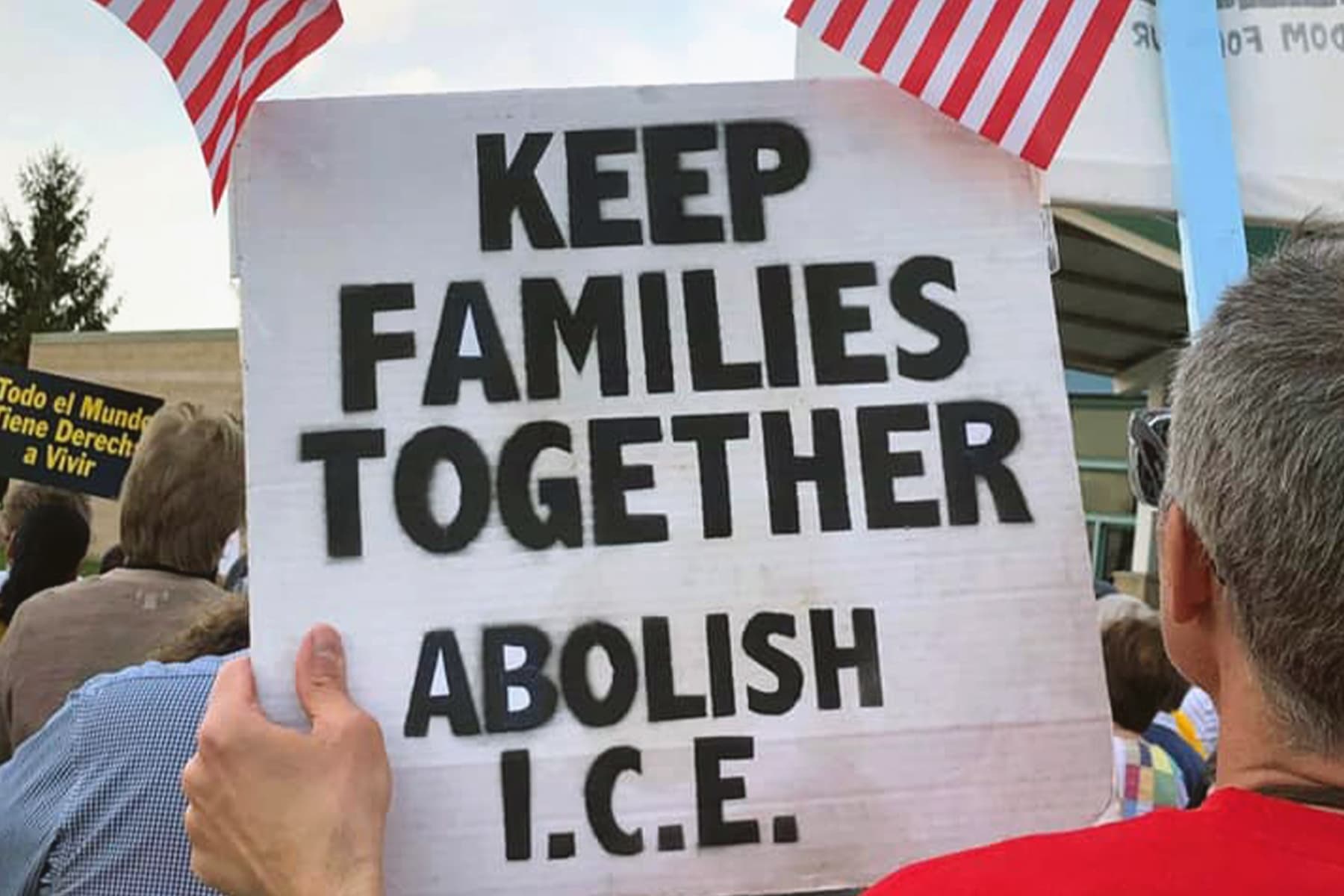

In the United States in 2019, Rendón and her husband were taken from their Chicago home in a military-style operation conducted by armed, uniformed ICE agents who had used their daughter to discover their location.

Paula Hincapie is still in the United States, protected by DACA, also known as the Dream Act, which allows her to stay here with her young daughter. She cannot, however, leave the country to visit her parents. Betty Rendón and Carlos Hincapie were deported to Columbia on May 28. They spent the time between May 8 and May 28 in detention, first in Chicago and then Louisiana.

News accounts of the incident refer to Betty Rendón as a “part-time pastor” at Emaus ECLA Church in Racine. In fact, she was a Ph.D. divinity student in Chicago who, “as part of her doctorate program, was placed here to do the Spanish-speaking worship for us,” said Mary Janz, now retired, who served as pastor at Emaus for twenty-five years. Originally founded by Danish immigrants, Emaus now has a small congregation of about 120, equally divided between English and Spanish speakers, Pastor Janz said.

Rendón would have begun her doctoral studies this summer at the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago, according to ECLA Bishop Michael Rinehart.

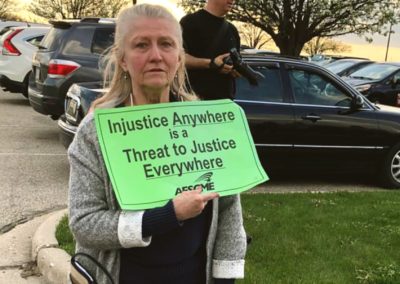

Both the arrest of Pastor Betty and the way it was conducted have left behind a traumatized community. Jessica Diaz of the Interfaith Coalition said, “People look at how a pastor and a religious leader was taken this way – in a military-style operation – and they feel like, if that’s what they do to a pastor, what will they do to us?” Pastor Betty’s arrest, she said, has “escalated the fear.”

“This is a crazy time,” Pastor Janz agreed. “We’re still working our way through all of this. There was a lot of emotion on the 28th when we held the prayer vigil here for Pastor Betty and others.” The Racine Interfaith Coalition, Emaus ELCA, Voces de la Frontera, and Racine’s Mayor Cory Mason participated in the prayer vigil at the church for Pastor Betty and her family on the day of their deportation.

Responding to questions about Pastor Betty’s deportation, David Liners of Wisdom said, “People are angry and people are afraid.” Liners thinks Rendón’s arrest was an “attempt to silence the community” which has been “active in speaking out against deportation.” Rendón, Liners said, had “been in plain sight for a very long time.”

During his presidency, Barack Obama was known as the “deporter-in-chief” because more people were deported under his administration than that of any other president, including Donald Trump. But President Obama’s policy focused on two things: using formal removal policies against those who crossed the border illegally, rather than just returning them, and on noncitizens with criminal records as the top enforcement target.

In the Trump era, being undocumented seems to be viewed as a criminal act, and deportations are random and across the board. Deportations also seem to focus on obvious targets, without regard to the value the undocumented person may have to the community.

Christine Neumann-Ortiz, executive director of Voces de la Frontera, has spoken out against the suffering caused by deportations like Pastor Betty’s as well as less high-profile figures, like Raymundo, a Green Bay grandfather who has been in the United States for thirty years, working to support his family doing seasonal landscaping and snow removal. He was recently stopped for driving without a license and now faces deportation.

As Neumann-Ortiz points out, DHS is using taxpayer money “to deport someone who is supporting their family. They’re not using prosecutorial discretion. Judges formerly could look at the facts, [determine that] this person is not any kind of threat. Now with the Trump administration, they are not exercising that.”

Immigration attorney Munjed Ahmad, of Ahmad & Guerard LLC, agrees that since President Trump took office, “Cases that were once closed due to prosecutorial discretion are no longer being closed.” Ahmad said that ICE is moving much faster than in the past, “and I believe that’s because of the AG’s edict to them.”

Donald Trump’s first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, issued a memo early in his tenure that stated, “there should be no blacked-out courtrooms, if there is a space available, that space should be used,” Ahmad said. The Attorney General wanted to “speed up the deportation process,” said Ahmad. For immigration lawyers this “made us have to scramble a lot faster than we used to in order to prepare a case,” he said.

The law as to who is eligible for a defense based on their immigration status has not changed, but the “willingness” on the part of government attorneys to negotiate “has become more difficult and more strained,” Ahmad said. “I believe they have no choice. I believe they’re getting orders from the top.”

Attorney Ahmad said that his clients, who include members of the Muslim, Latino, and African communities, are more apprehensive since Donald Trump took office.

But as Neumann-Ortiz pointed out, immigration infractions are a civil, not a criminal offenses. No U.S. citizen could be held in a jail or detention facility for a civil offense. But once someone is found to be undocumented, they have no rights.

Lacking any means to “legitimize their status, people are forced to live in the shadows with the threat that they could be separated from their loved ones, even if they’ve lived here 30 years” like Raymundo, Neumann-Ortiz said.

Voces de la Frontera is currently promoting a statewide initiative called “Defending our Families, Restoring Drivers Licenses.” The Real ID Act of 2005, sponsored by Wisconsin Congressman James Sensenbrenner, required applicants for a driver’s license to submit proof of citizenship or legal resident status.

Another statewide general strike is possible, Neumann-Ortiz said. The last two daylong strikes were successful in defeating Republican “anti-sanctuary” legislation. “All change is bottom-up” Neumann-Ortiz said. “We’re working to elevate all these voices in the cities, suburbs, rural communities” so that people can be made aware of the contribution of immigrant communities and how much society as a whole relies on them. “It’s really blind bigotry that’s driving [the deportations],” Neumann-Ortiz said.

© Photo

Family photo and Emaus ECLA Facebook Page