Ahmed Hassan, M.D. was one of the presenters at the two day Behavioral & Mental Health Conference focusing on addiction treatment and how conventional mental health services often fail to provide culturally sensitive care.

How many Muslims in America are alcoholics? Addicted to heroin, cocaine, crack or hallucinogens? What percentage of opioid addicts are Muslim?

Do American Muslims with substance abuse disorders seek treatment? Do they respond to treatment in the same way as Americans of other faiths or no faith at all?

“Research on the prevalence and treatment of substance abuse among Muslims in the United States, as well as effect treatment, is very scarce,” Ahmed Hassan, M.D., told mental health professionals, academics, physicians and others at the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition’s second annual Behavioral & Mental Health Conference: Mental Health & The Muslim Diaspora, where more than 140 attended to hear national and international experts on mental health.

Dr. Hassan presented what he said is “the first study to report the prevalence of various substance abuse disorders among the general Muslim population living in the United States from a nationally representative sample.” He also shared a treatment model designed for Muslims that integrates Islamic teachings with evidence-based treatment approaches, noting that the two align in interesting ways.

In his presentation, Faith-based Psychoeducation Program for Addiction Treatment: The Harmony Between Science and Religion, Hassan said, “Conventional mental health services often fail to provide culturally sensitive care.

“Muslims face distinctive challenges, unmet care needs and addiction stigma as impediments to treatment. Interventions that acknowledge spiritual, cultural and personal ideals impart hope and meaning.”

The Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition’s second annual Behavioral & Mental Health Conference: Mental Health & The Muslim Diaspora, attracted over 140 attendees.

Other conference presentations covered by WMJ are:

- Dr. Kameelah Osequera, founder of the Black Muslim Psychology Conference and the founder and president of the Muslim Wellness Foundation on why white supremacy is bad for our mental health, and

- Duaa Haggag, M.A., L.P.C., a community educator with The Family & Youth Institute, a national research and educational institute that focuses on Muslim mental health and family wellness on the United States’ loneliness epidemic.

(See the full conference at these links: Day One and Day Two.)

Addiction among American Muslims

Hassan and his colleagues at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health developed the first research study using a nationally representative sample on the prevalence of addiction among self-identified Muslims. Hassan is a clinician scientist and addiction specialist at the center, and an assistant professor in the University of Toronto’s Department of Psychiatry. He is also a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and a Diplomate of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology.

This study, The prevalence and treatment utilization of substance use disorders among Muslims in the United States: A national epidemiological survey, was published in June in The American Journal on Addictions.

How do Muslim Americans compare in addiction rates to other groups?

Their research showed Muslim Americans have lower prevalence of alcohol addiction, higher tobacco addiction and similar prevalence of other substance addictions when compared to the general U.S. population.

The prevalence of alcohol addiction among Muslim adults in the United States is at 11%, lower than the general population at 18.5%, he said. However, addiction to other substances like cocaine, club drugs, sedatives and opioids are similar to the general population.

Their research on alcohol abuse aligns with a 2009 Gallup poll finding that 14% of Muslim Americans disclosed alcohol binge drinking, the second lowest among the groups surveyed.

Ahmed Hassan, MD, FRCPC, MPH, psychiatrist/assistant professor at CAMH & University of Toronto

“The strict prohibition of alcohol in Islam, often deeply internalized, serves as a protective factor against initiating alcohol use among Muslims,” their research reported. “One study reported that Muslim religiosity acts to prevent the initiation of substance use; however, once the substance has been initiated, the risk of developing a substance abuse disorder is the same as the general public,” they noted.

Muslims born outside the United States are less likely to have alcohol addiction, Hassan said. “Acculturation is likely to explain this finding. “Based on our findings, we anticipate that without individualized intervention, the rate of alcohol use disorder is expected to increase with second-generation Muslims born in the United States.”

Muslim Americans’ addiction to tobacco is higher than the general population at 18.5% compared to 17%. A contributing factor could be the influence of the native countries where tobacco use is common, he said. In Muslim majority countries, tobacco use disorder is at almost 30%, research shows.

Muslim Americans disclosed the highest prevalence of smoking (24%) compared to other religious groups and higher than the U.S. general population in a 2009 Gallup Poll, Hassan noted. “Muslims in the U.S. have higher rates of mortality associated with elevated tobacco use than other groups. Tobacco is not as strictly prohibited in Islam as alcohol.”

Other substances, such as cannabis and stimulants, have not been directly prohibited by the Quran, causing debates about whether or not they are permissible, although most, if not all, scholars confirm that they are, he said.

Need for culturally sensitive addiction treatment for Muslim Americans

Muslims in the United States are among the most diverse ethnic minority groups, coming from 75 different countries, Hassan said. More than 60% are foreign-born. Despite their heterogeneity, about 75% of Muslim Americans identify strongly with the global Muslim community, he said.

In addition, American Muslims are the youngest faith group in the U.S., with 1/3 under 30 years old, making them especially vulnerable to the risk of substance use disorder, he noted.

“Through acculturation, Muslim’s cultural beliefs are influenced by both their native and host countries. For example, research on U.S. Muslims found that individuals with less acculturation are more likely to use tobacco than those who are fully acculturated.

“Many Muslim Americans identify religion as an important aspect of their lives. In Islam, the use of harmful substances and intoxication is strictly prohibited, which protects practicing Muslims from initiating drug use,” he said.

However, Muslims who do begin substance use may be especially vulnerable because they are engaging in behavior considered to be taboo, he said. “Affected Muslims cannot openly discuss their substance use with their own communities for fear of being rejected or ostracized.”

Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ahmed Hassan

Collective denial, like the widely held assumption that Muslims don’t drink alcohol, results in under-recognizing the true extent of substance abuse in the community, he said. Even non-Muslims health care providers may not properly screen Muslims for drug use because of these assumptions. This causes isolation and lack of recognition of Muslim addicts that may result in a spiritual crisis and poorer prognosis of substance abuse disorder.

“Additional factors that compound the risk of substance abuse disorder among American Muslims include stress and trauma resulting from sociopolitical considerations. Muslims in the United States face significant religious discrimination that surpass that of all other religious groups … Furthermore, many Muslims in the United States have migrated from countries that were impacted by war, poverty, famine, displacement, or instability, resulting in traumatic experiences. Trauma exposure is another risk factor for substance abuse disorder.”

The risks for Muslim Americans are further worsened “due to the significant lack of tailored prevention and interventional services,” their research found.

Culturally informed treatment

Muslim Americans with addictions experience a “double stigma,” Hassan said. For example, alcoholism already carries a stigma in American society. That stigma is compounded in the Muslim American community by fear of social consequences.

As a result, addiction has a significant negative impact on mental health, and emotional and social functioning in Muslims, he said. It also may prevent them from seeking treatment, in order to keep their addiction hidden.

“It is essential to address addiction in Muslims due to the unique needs and challenges of this minority group,” he told the conference attendees.

Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ahmed Hassan

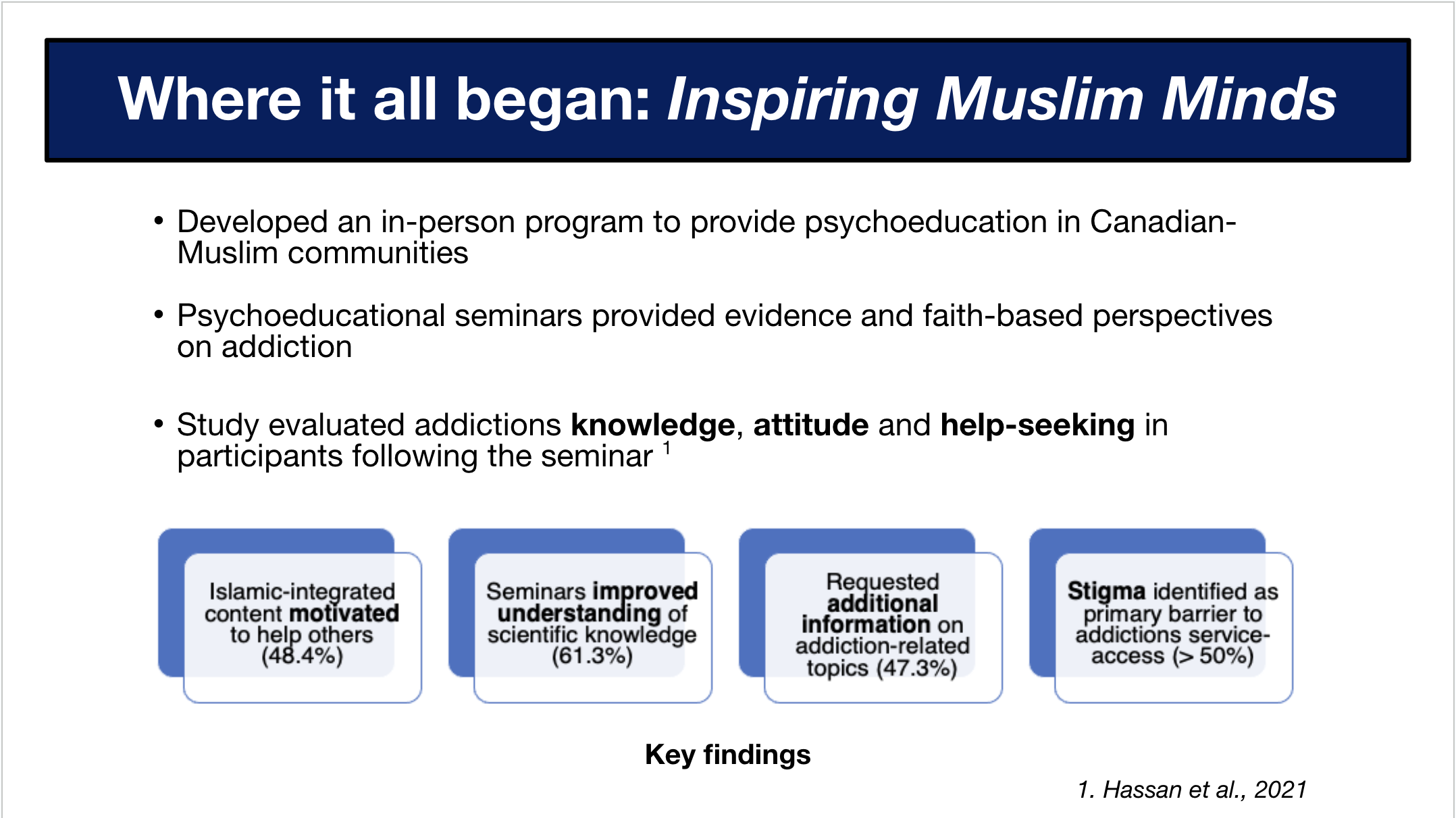

Hassan and his colleagues have designed a novel, faith-based psychoeducation program called “the Canadian Muslim Addiction Program,” or “C-MAP.” He described C-MAP as a comprehensive program that integrates Islamic teaching and evidence-based treatment.

“A systematic review of 24 studies on Muslims indicated that affected individuals expressed the need of support of religion to facilitate treatment. They want the involvement of religion and spirituality in their care.”

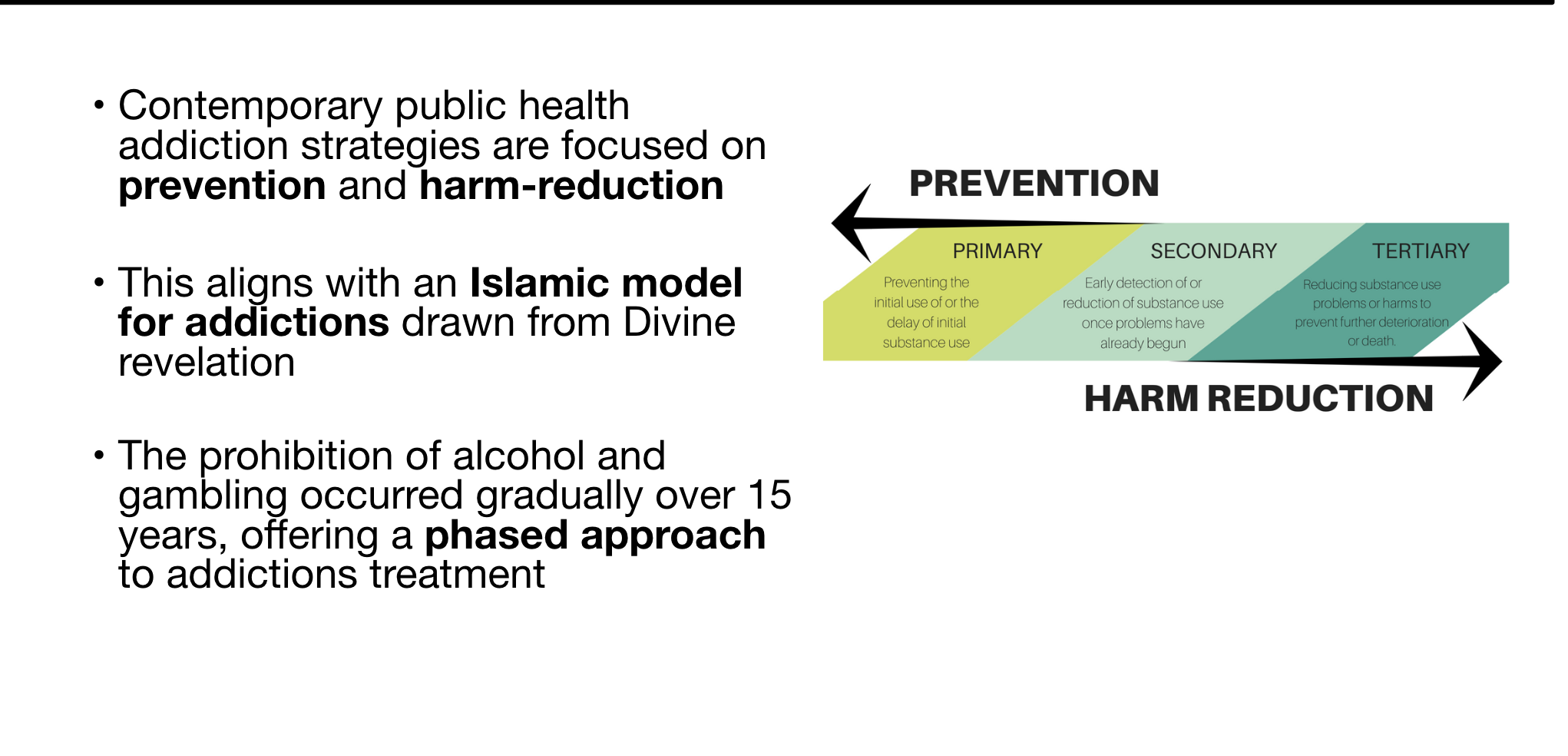

Modern public health approaches to addiction treatment align with Islamic models drawn from Divine revelation, Hassan said. “Contemporary public health addiction strategies focus on prevention and harm-reduction,” he said. Islamic teachings offer similar approaches, he said. For example, “Islam’s prohibition of alcohol occurred gradually, offering a phased approach for addiction treatment. It did not restrict alcohol from the first day and it focused on harm reduction.”

Quoting from G. Hussein Rassool and Mugheera M. Lugman’s 2023 textbook The Foundations of Islamic Psychology, Hassan explained, “The objective (of Islamic Psychology) is to advance psychology and the spiritual dimension of human nature, not as two opposing fields but as complementary and holistic approaches in the understanding of human behavior and experiences.”

“To best serve minority/racialized groups, interventions should be culturally and religiously adapted,” he said. Research on their integrated approach showed that the Islamic content proved to be motivational. Likewise, statistics about overcoming addictions also proved to be motivating, he said.

Hassan “began incorporating aspects of faith into my practice with evidence-based scientific approaches like cognitive based therapy and I began to hear from other psychologists that this is something they are looking for.”

One example is Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) teaching: Every intoxicant is prohibited; what intoxicates a person in large amounts is forbidden in little amounts. Integrated treatment adds information about the bio-vulnerability, Hassan said. “We tell people there is the genetic component. You might not be able to stop it.”

Another example is to encourage God-consciousness and the rewards of change, he said. Awareness of God may help one avoid wrong actions. That idea may be combined with the health benefits of change suggested by neuroplasticity, the ability of the nervous system to repair itself by reorganizing itself after injuries, such as stroke or brain trauma. That knowledge fosters hope, he said.

Graphic courtesy of Dr. Ahmed Hassan

About the MMWC Behavioral & Mental Health Conference

With support from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services and Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin, MMWC’s annual Behavioral & Mental Health Conference began in 2021 as a two-day conference for mental healthcare professionals to provide education that will help them better serve Muslim patients. Through collaboration with the Medical College of Wisconsin, attendees were able to earn CME credits.

The 2nd Annual MMWC Behavioral and Mental Health Conference, Mental Health & The Muslim Diaspora: Proving Guidance Through a Cultural Lens, aimed “to provide context, information and strategies to help providers gain greater cultural competence when working with members of the incredibly diverse Muslim community,” wrote MMWC founder and executive director Janan Najeeb in the conference welcome message.