Photo by Kamal Shkoukani

Dr. Kameelah Osequera (right) praised her mentor Dr. Farha Abbasi (left) for her research that put a spotlight on Muslim mental healthcare in America.

During many years as a college counselor, Kameelah Mu’Min Oseguera, Psy.D., often asked students where they were from. “To a person, my white students would say, ‘I’m an American,’” she noted. If she pressed, they would name a state or a city.

When she spoke to students of color, “they would give me not just that they were American, but there’s a hyphen.” They felt the need to qualify “who I’m connected to” and “why I’m here.”

Both answers reflect the toxic impact of white supremacy, Oseguera said Saturday at the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition 2nd Annual Behavioral and Mental Health Conference. “White supremacy is a system of oppression that impacts everyone in it. This isn’t something we’re studying simply because it has this detrimental impact on minoritized communities. Those who have privilege because of their racial background are also negatively affected by the system. This cannot be overstated.”

What does it mean for each of us—those who identify as the majority and those marginalized alike—to live in this toxic social environment of white supremacy and Christian hegemony? How can we control the impact of these toxins we breathe in every second of every day? What is our level of consciousness of those things that impact us also on a daily basis? Oseguera explored these questions in her talk Until It Is Faced: Reflection on the Impact of Anti-Black Racism, Islamophobia and White Supremacy on American Muslim Communities.

Dr. Oseguera is a scholar whose research interests include spirituality in psychotherapy, wellness and community resource building, mental health stigma in faith communities, racial trauma and healing, and faith-based activism. She is a visiting assistant professor of psychology and Muslim studies at Chicago Theological Seminary, founder of the Black Muslim Psychology Conference and the founder and president of the Muslim Wellness Foundation,

See Dr. Oseguera’s talk and more MMWC Behavioral and Mental Health Conference presenters at this link.

Photo by Kamal Shkoukani

More than 140 people attended the 2nd annual MMWC Behavioral and Mental Health Conference last weekend.

Giving mental health providers a cultural lens

The 2nd Annual MMWC Behavioral and Mental Health Conference, Mental Health & The Muslim Diaspora: Proving Guidance Through a Cultural Lens, aimed “to provide context, information and strategies to help providers gain greater cultural competence when working with members of the incredibly diverse Muslim community,” wrote MMWC founder and executive director Janan Najeeb in the conference welcome message.

Experts in the field of Muslim mental health from around the country and internationally presented to 144 attendees, said conference organizer Mohamed Amine Ouzif, MMWC project coordinator. The audience included mainly mental health providers, healthcare providers, academics and graduate students from across Wisconsin.

Najeeb thanked the Wisconsin Department of Health Services and Froedtert & the Medical College of Wisconsin “for their generous support” of the conference.

Impacts of white supremacy

“We are not born as racist people. We are not born as marginal people,” Dr. Oseguera said. “We are born with the ability to breathe free.

“We Muslims believe there is a natural fitra (an Arabic word referring to the state of purity and innocence in which all humans are born),” she explained. “But we live in a world full of what Cornell University Professor James Garbarino calls ‘social toxins’” that affect our identities and our environment. “Every single one of us takes these in. They are embedded in every aspect of our lives. They impact how I think about myself, my humanity, my worth and my sense of belonging.

The fruits of white supremacy are anti-black racism, Islamophobia, sexism and xenophobia, to name a few, Oseguera said. “If these toxins were radio-active, we’d all glow in the dark.”

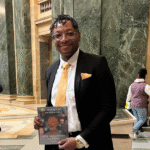

Kameelah Mu’Min Oseguera, Psy.D., founder and director of the Muslim Wellness Foundation

Giving a personal example, she described the challenge of discovering her family tree. She has tracked it back to “Joseph and Mary, born free in Virginia in about 1812. They were agents on the Underground Railroad. As the son of the daughter of the son of the daughter of the son of a descendant of enslaved people both in the United States and the Caribbean, being able to trace my lineage in this way has taken me 32 years.”

Being inspired by “the faith and resilience of all those who came before me … is an important intervention into understanding the stories of white supremacy because this was not supposed to be available to me.”

But it is not only the minoritized and the marginalized who are affected, she emphasized. “To be white in America is to not have to think about it,” acclaimed diversity scholar Robert W. Terry wrote in 1981, recalled Oseguera. But not without consequences, she added.

“The impact of white supremacy on those with privilege (the unquestioned and unearned set of advantages experienced by whites) is internalized dominance, she said. If you are in a system of belief where you are led to believe you are superior to everyone else, how do you build authentic relationships? If the world tells you that everyone else is beneath you … that does something very damaging to someone with privilege. It can also lead to feelings of guilt and resentment.”

Name it

Oseguera also took inspiration from acclaimed author and poet James Baldwin, who in a 1962 article in the New York Times urged writers to “speak about the world as it is” with “as much of the truth as one can bear.”

Baldwin “is giving us the courage to understand that not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can change until it is faced. Change begins with understanding the truth of our circumstances.”

She urged her audience to go to the underlying system at the root of the problem—white supremacy. “If you do not understand white supremacy, what it is and how it works, everything else you understand will only confuse you. White supremacy is invisible—to confuse and confound us, to keep us unsettled. Something is happening to me but I don’t know the source.

White supremacy is “the ideology that white people and the ideas, thoughts, beliefs and actions of white people are superior to people of color and their ideas. It is also a political and socioeconomic system where white people enjoy structural advantage, and this structure has been centuries in the making.”

No one is outside the system, she added. “We all live in it, breathe it in and it impacts us.”

Oseguera said she doesn’t call it white supremacy to be provocative or radical. “It is naming. As physicians and mental health providers, we know it is difficult to get to the root of the problem without an accurate diagnosis.” By naming it, we can develop a strategy that takes into consideration what the toxin is, she said.

Using language accurately

Once we know white supremacy is at the root of the afflictions (racism, sexism, Islamophobia, etc.), we use more accurate language, she said. When one understands white supremacy is a system operating on each of us, we no longer talk about minorities, Oseguera noted. People of color are actually the majority in the world. “I am not born in a minority. I am born into a very vibrant, beautiful, joyful community.” It is the system that minoritized and marginalized people of color.

“In the same way, I talk about myself as a descendant of enslaved Africans. I am not a descendant of slaves. Being a ‘descendant of enslaved people’ means there was a condition operating on people in those circumstances.

“We have to be mindful of how we erase the oppressor in our language.”

Photo by Kamal Shkoukani

Dr. Farha Abbasi, Dr. Kameelah Oseguera, Dr. Munther Barakat, Dr. Asma Iqbal and Dr. Azhar Yunus discuss barriers to accessing mental health care.

Creating a new story

To create a new story, we must first come to terms with the current one, she said. This begins by naming it. Then we see how white supremacy “has become embedded in our collective consciousness worldwide,” Oseguera said.

For example, “because of the industry of Islamophobia, in everything from movies to video games, who is the villain in some vaguely desert-like place? My 7-year-old son, 22 years after 9/11, said to me the other day, ‘I don’t like movies where the white people are the good guys and Black people and Muslim people are the bad guys. He is 7 and he notices.”

Consider Ramadan and fasting, the “beauty of breaking the fast at an iftar (dinner) feels very special. But there is a belief (among some non-Muslims) that something is wrong. That Muslim fasting is extreme. They ask, ‘Why would your religion want you to do that?’

“To consciously resist what is seen as normalized, you have to be aware.”

Oseguera offered many more examples of the ways white supremacy marginalizes people. Then she urged the audience to go beyond naming what is happening to them to imagining a world without whiteness as an ideology.

In order to create it, first we have to imagine it. “What might that be?” she asked. “Let’s imagine you woke up tomorrow and all the -isms were gone. What would you do? If you lived in a world in which you are not so deeply negatively affected, who would you be?”