© Photo

IFWG Publishing International

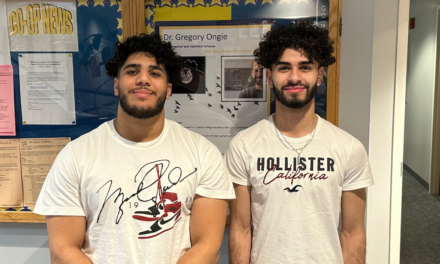

David Bowles is a writer, poet, and professor who has won numerous awards for his books and has been multiply anthologized. He teaches English and Spanish literature as well as Aztec and indigenous mythology, an interest finds its way into his writing. His YA and science fiction books in particular are heavily infused with indigenous myths and stories – think Neil Gaimon with an Aztec vibe, combined with stories of the contemporary southern borderlands. Bowles is a 2017 inductee into the Texas Institute of Letters.

Not only that, but he has more than 16,000 followers on Twitter. So when he tweeted about the Arabic roots of many Spanish words, it caught the attention of lovers of Arabic.

For example, on Twitter Bowles revealed the Arabic roots of the word “barrio,” which today is fairly commonplace in English as well as Spanish, and describes a neighborhood where primarily Latinx people live, as derived from “Andalusi Arabic بَرِّي ‘barri’ (‘exterior’), which meant the rural, less civilized edges of a city, from Classical Arabic بَرِيّ ‘barriyy’ (‘wild’). Cognates are Portuguese ‘bairro’ and Catalan ‘barri.’”

The term “Andalusi” is key to understanding our present-day use of the term “barrio.”

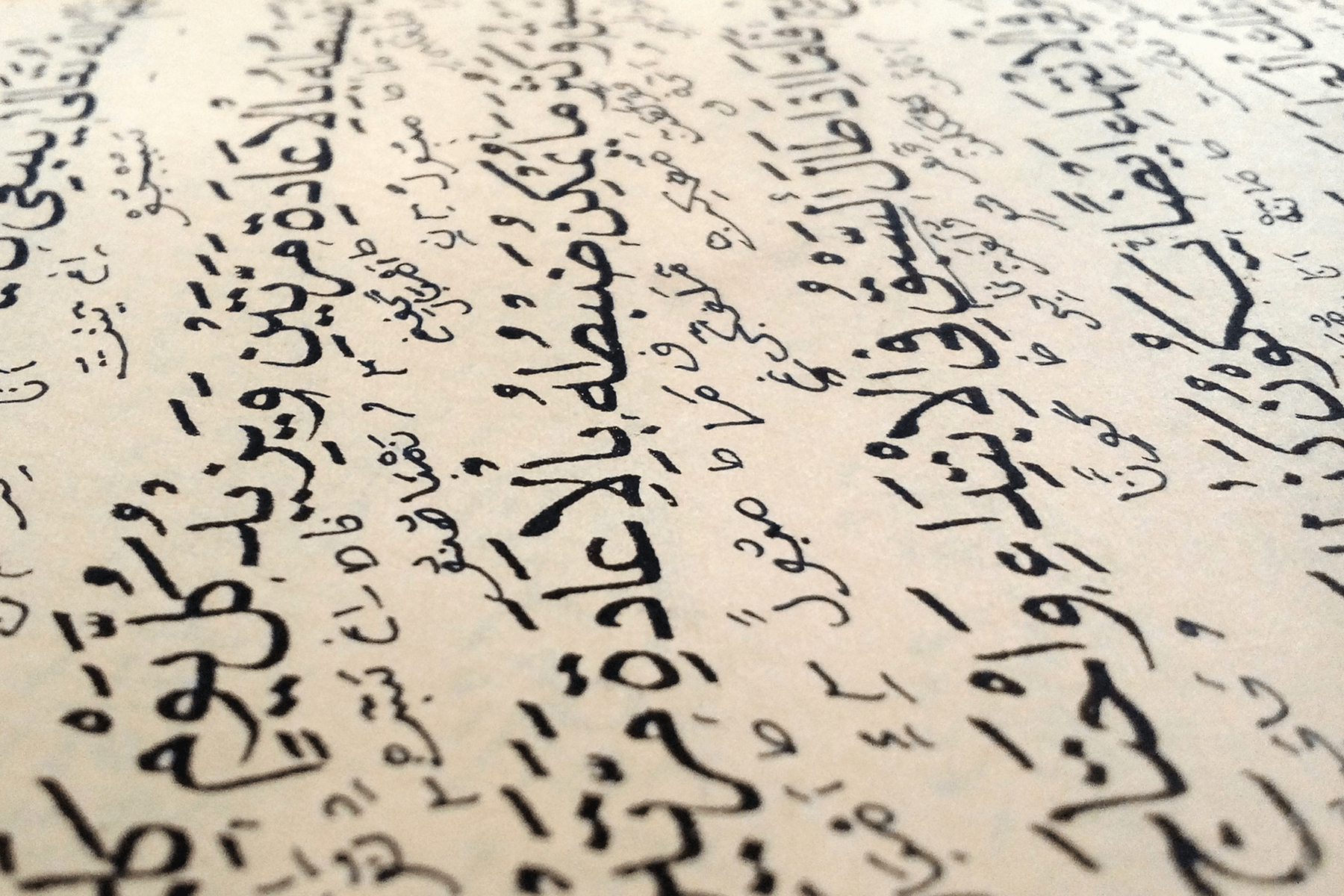

On his Twitter feed, Bowles explained that “Spanish has some 1,000 Arabic roots and about 3,000 derived words, so nearly 4,000 total, 8% of the language, the largest influence on the Spanish lexicon (not counting Latin). Before the ‘Reconquista,’ that percentage was much higher. Swahili has around 2,300 (Arabic-derived words) by comparison.”

For lovers of history, it can come as no surprise that the infusion of Arabic into Spanish dates back to the Islamic Caliphate of Southern Spain, which, under a succession of rulers, controlled the southern Iberian Peninsula from Muslim general Tariq ibn-Ziyad’s landing on Gibraltar in 711 until the “Reconquista” of Ferdinand and Isabella in the late 15th century.

Muslims called this conquered territory Al-Andalusi, and the region is still sometimes referred to as the “Andalusian peninsula.”

Until that time, Spain had been ruled by the medieval Christian Visigoths, and its version of Latin was in the process of evolving into a Romance language of its own. Arabic, therefore, was a key feature in the language evolving on the Peninsula.

UWM professor Hamid Ouali, an expert on Arabic linguistics, wrote in an email that, “Spanish borrowed vocabulary heavily from Arabic in different domains, and some of this vocabulary still exists in the Spanish lexicon. Every Spanish word that starts with ‘A’ or ‘AL,’ for example, most likely originated from Arabic.”

According to Ouali, Arabic words became an integral part of Spanish, from the obvious place names, like “Alhambra” from the Arabic word “Al-hamra,” the “the red castle,” to the names of day-to-day items like “almohada” from the Arabic word “al- mukhadda,” which means “pillow,” or “aceita” from the word “zeyt” meaning “oil,” and “Azucar” from “Assukka”’ meaning “sugar.”

Thomas Glick, who wrote about Islamic Spain in the early Middle Ages, describes the Spanish Caliphate as “a society dominated by Muslims, with provision made for approved religious minorities, characterized as dhimmis (‘protected’ peoples) or ‘People of the Book’ (those with a revealed scripture recognized by Muslims as divinely inspired – that is, Christians and Jews).”

According to Glick, this was a society, not of oppression of minority groups, but of relative freedom for each group to pursue its own religious and cultural practices, though becoming Muslim was a prerequisite for gaining power and stature.

Bowles, who recommended Glick’s article, has his own take on Medieval Spain, where the largest population group was the “Muladis or Muwalladūn. A Muladi/Muwallad was sometimes a person of mixed heritage [but they were] usually. . . just people of European stock whose families were Muslim, who were brought up in ‘Arabic’ Andalusi culture.”

But the Catholic northern kingdom of Castile on the Iberian Peninsula was not content to let the situation rest. “By the end of the 13th century,” Bowles says, “it was clear Castile was winning the centuries-long struggle for dominance on the Iberian Peninsula. Castilian was overlaid upon the Andalusi Romance spoken in conquered cities.”

Bowles goes on to say, “Some folks want to imagine the Christian kingdoms that pushed their way south over hundreds of years as the true ancestors of the modern Spanish people, as if Catholic conquest scoured Islam and Muslims from their bloodline and culture. No. Most Muwalladūn remained. Converted.”

Bowles learned about the linguistic overlap between Spanish and Arabic while still a graduate student “decades ago,” and says that most people “don’t recognize the extent to which or how those words got into the language. There are so many things about the world people don’t know. This is one of the reasons I use my twitter account the way I do.”

The lessons of Medieval Spain and the Islamic Caliphate continue to be relevant, especially in these overheated times when fear of the immigrant as Other seems to have become so widespread. “I have a lot of friends in Spain and [the] tensions with the immigrants from Africa [are] disheartening,” Bowles said during a phone conversation, adding that in American as well as in Europe “this fear of immigrants and this scapegoating of them,” exists largely due to ignorance.

“People need to be confronted with the fact that the language they speak and the culture they participate in is deeply rooted in Africa,” Bowles said. “So I thought, why not share it and use my platform – I have a respectable number of followers – to popularize this.”