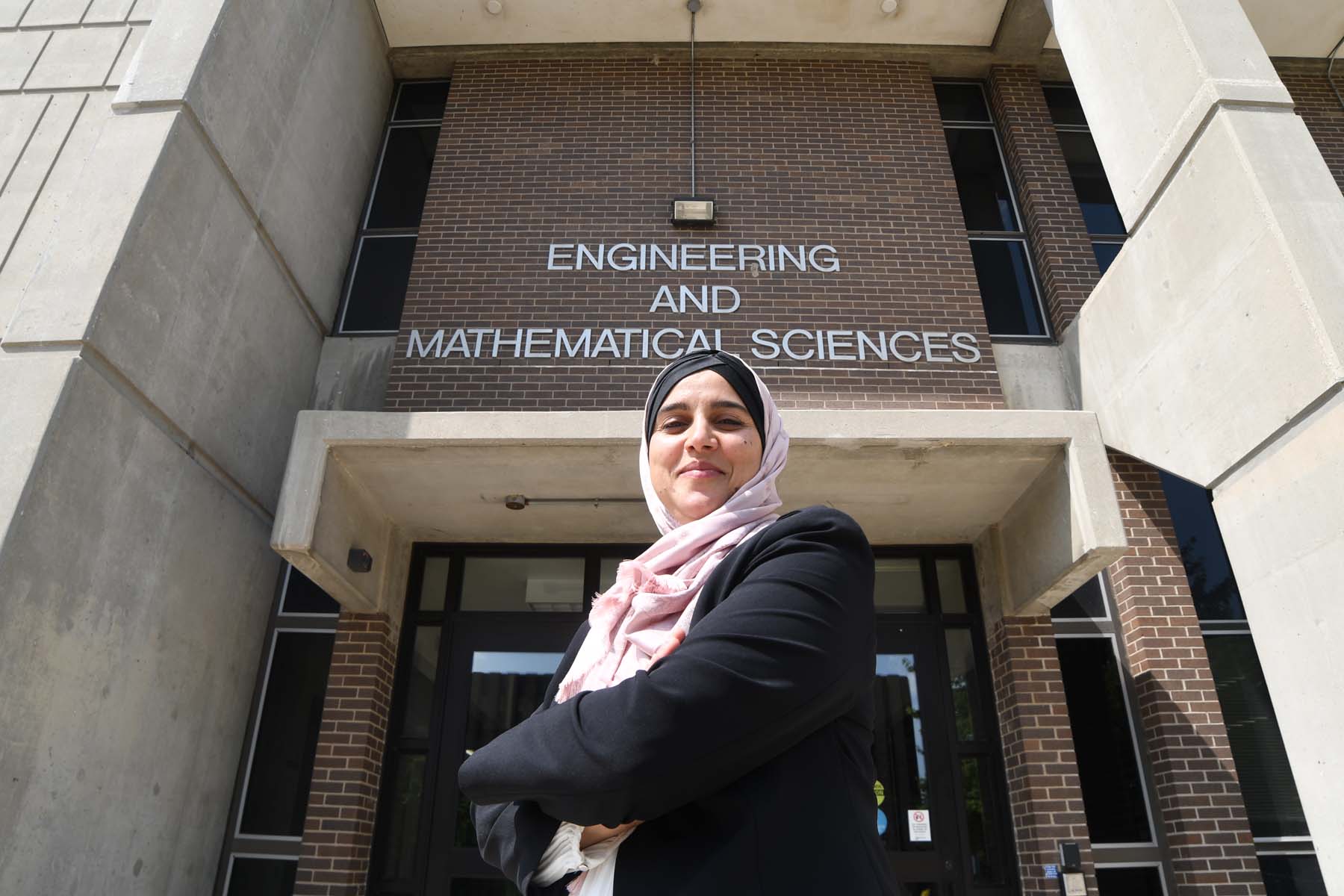

© Photo

Lila Aryan Photography for the Wisconsin Muslim Journal

Hanaa Alqam sees herself first as a mother of three kids, then as a mechanical engineer. “I feel like I’m a very ordinary woman, not with that sparkly smartness.”

And yet, this May, the mother of sons Aubai, 11 and Eyas, 2 and daughter Amal, age 8, was awarded her PhD in mechanical engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her thesis, on optimization techniques, is titled “The Response Transmissibility Developed by Optimal Sensor Locations.”

More important than the fact that she knows what this means and can explain it to others is that, like a born teacher, she has the gift of inspiring others.

Hanaa and her husband, Kamil Samara, now an assistant professor at UW-Parkside, came to Milwaukee in 2007 so he could work on his PhD at UWM. At that time, Alqam, a Palestinian, had already done her masters in her adopted country of Jordan.

“I was pregnant with my first baby when we came over here,” she says, “it was not an easy decision for me to go back to school.” But with the encouragement of her husband and a supportive family, she was able to enter the engineering graduate program at UWM in 2008. “I had been always dreaming of being a professor. I really enjoy teaching,” Dr. Alqam says. And more importantly, she was able to “overcome this fear of starting over. We launched our life here from zero.”

That fear is not an unusual one, even for highly educated women. Dr. Alqam says she has many friends who got their degrees only to find themselves staying home and raising families.

“I know a lot of women who came with their husbands, they did their bachelor’s degree and then became moms but didn’t pursue their dream. It took me longer” than most single, younger students, “but I was determined to finish.”

But if there’s one thing she now knows, “one person cannot achieve his goal by himself. I received support from my family, the community, and even my school.” Her thesis supervisor, Anoop Dhingra, was also a strong source of support and encouragement.

“After I gained my PhD, I got a lot of comments from my friends,” who wanted to know, “how did you do it? They think I have superpowers! I always feel like I am an average person. I just have the dreams.” What you need is the drive and determination to achieve your goal, “that’s enough.” Dr. Alqam says.

Hanaa Alqam currently teaches bio-medical systems modeling, part a program that is relatively new to UWM, biomedical engineering.

She teaches an introductory course on “how to model any system – electrical, mechanical – from physical to mathematical,” Alqam says.

The course includes a healthy dose of systems analysis, and, she says, “We do different types of systems every week,” including complex systems, “like developing the manipulation for an artificial or robot hand,” a project currently underway in UWM’s bio-medical engineering program.

“UWM is developing new labs and attracting more students in this area,” creating solutions that are at the forefront of medicine, Dr. Alqam says. “We all work as a team to get that product.”

The number of women in engineering is growing. However, much as universities and secondary schools talk about encouraging women to study in the STEM fields, acquiring that education has not become any easier.

“Women are struggling in this field,” Dr. Alqam says. “I was hoping that, moving from Jordan to a developed country like America, I would not see that struggle.”

But she did, and it was not a struggle of harassment or competition with male colleagues, rather one of the basic logistics of managing a family and being a mom with a husband who for a time was driving sometimes four hours a day to teach at Illinois Wesleyan.

“Paying for childcare is part of that struggle,” she says. And even where childcare is more available, as it is on the UWM campus, which has an excellent daycare center and widely available nannies and babysitters, it is expensive. Here in America, unlike other developed nations, middle-class mothers must pay out of their own pockets for someone to take care of their children while they are attending classes and working in research labs – let alone when they have professional jobs.

“That’s one of the big challenges” in the United States,” Alqam says. “Even maternity leave is not paid for.” And that makes “achieving the balance of being a mother” and a professional that much more difficult, Alqam says.

“In my country there is always encouragement, it doesn’t matter what your gender is, as long as you’re studying something the market needs.” A new field, “mechatronics,” a form of programming used to achieve mechanical objectives, was just taking off while Dr. Alqam got her master’s.

“This is a brand new engineering field in my country. And I was so happy to take it. Everyone was encouraged to take it.” Some of the men Alqam studied with in Jordan, “got jobs in the Gulf area.” But many women with the same degrees stayed home and raised children. “Even in Jordan, after school, opportunity is not equal, though some women got a chance to work in certain companies.” Along with quite a number of women already living here, Hanaa “was hoping here in the States it would not be the same problem.”

And yet, while Dr. Alqam sees those political and social realities, she is anything but discouraged by them. She doesn’t want it to affect the next generation, like her eight-year-old daughter Amal, who wants to be a scientist. Alqam says she didn’t want her daughter to see her studying for years and then not using her degree.

Dr. Alqam’s mother, Vahijah, has been a great help. “I’m lucky I was able to bring my Mom, “without her help,” she says, it would have been “kind of impossible to achieve what I have done.”

But Alqam says her greatest strength in overcoming the “obstacles” life threw her way, was the wisdom taught by her Muslim faith. “I have been taught since I was a child that Allah created us for a reason. If a person develops their resources,” through getting an education, for instance, “they will be rewarded. And my rewards keep growing.”

Perhaps Alqam’s best advice to moms who want to achieve academic and career goals is that, “It’s okay sometimes to feel guilty towards your family. If one day is bad, it doesn’t mean that all life is bad.” In other words, if you can’t help with homework tonight, you’ll make it up another night.

“It took some time to accept that,” she says, but now, “I look at my achievement – I’m proud of it, and my kids are proud of me.”

Dr. Alqam wants “all women, mothers, to think about that. You do have something. Take advantage of that.” After all, she says “If we achieve success in this life, we also want God to be happy with us.”