Kayla Renée Wheeler for Middle East Eye

From writers and scholars, to activists and community organisers, artists and musicians, Black Muslims have played an integral role in fighting for Black people, even while in bondage.

The explosion of mass protests across the US against the killings of Black Americans George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and multiple others by police officers has reignited crucial conversations around anti-Black racism and the legacy of slavery across the globe.

The Black Lives Matter movement against anti-Black racism has gained new momentum and energy, taking place as Black people are dying at disproportionate rates from Covid-19 and unemployment rates have spiked. Simply put, many Black people have nothing to lose.

The movement has led many Muslims in the United States, especially non-Black Muslims, to seek out knowledge on the history of Black Islam in the US and to find ways to support the Black Lives Matter movement.

Black Muslims in the US are not immune from police violence: in 2018, Somali-born Shukri Ali Said, 36, who was suffering a mental health crisis, was shot and killed by police officers in Johns Creek, Georgia. The four officers involved in Said’s death were cleared of wrongdoing.

And then on 9 May this year, Sudanese-American Yassin Mohammed, 47, who may also have been in the middle of a mental health crisis, was killed by police officers, also in Georgia.

Mohammed and Said’s cases have drawn little attention outside of their local communities – an act of erasure which points to the persistent marginalisation within communities of both Black people with disabilities, and Black Muslims.

While the Black Lives Matter movement is only six years old, the fight for Black liberation in North America is over 500 years old, and Black Muslims have often been at the centre of it. From writers and scholars, to activists and community organisers, artists and musicians, Black Muslims have played an integral role in fighting for Black people, even while they were in bondage.

Of the plethora of relevant books available on the subject, five texts stand out for their accessibility and ability to help contextualize the relationship between the current uprisings and Islam and Muslims in the United States and beyond.

1. Servants of Allah by Sylviane Diouf

Upwards of 30 percent of all enslaved Africans transported to the Americas were Muslim, with the vast majority going to the Caribbean and South America, most notably Brazil.

Published in 2013, Sylviane Diouf’s book, details how enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and Americas resisted white supremacy, maintained connections to other Africans across the diaspora – and, in some cases, the African continent – and were able to find ways to practice their religion under intense surveillance.

The book highlights several important Black Muslim figures in the Americas including Omar ibn Said and Bilali Mohamed – both writers and Islamic scholars whose intellectual legacy is still felt today.

Diouf notes that many enslaved Muslims were trained soldiers who used their tactical knowledge to lead slave revolts. For instance, the Malê Revolt in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil was led by free and enslaved Muslims during Ramadan in 1835. While the rebels were ultimately defeated, the uprising played an important role in pushing Brazil towards abolishing slavery.

Servants of Allah was one of the first English language books published on African Muslims and the transatlantic slave trade, joining Allan D Austin and Michael Gomez’s foundational work on enslaved Africans in the Americas. Like Gomez, Diouf moved beyond biographies of individual Muslim men to explore the diasporic nature of Islam in the Americas and Caribbean.

The book became popular after 9/11, three years after its original publication, because it showed the long roots Muslims have had in the United States. It challenged assumptions that Islam was foreign and new to the US. Non-Black Muslims were “eager to demonstrate that Islam was as much of an American religion as any”.

According to Diouf, Servants of Allah helped Black Americans legitimise their connections to Islam with non-Black Muslims, who questioned their authenticity. Reading the book in the age of Black Lives Matter allows readers to see how anti-Blackness and Islamophobia are interconnected: both were central to founding the Americas and Caribbean, and Black liberation is tied to ending Islamophobia.

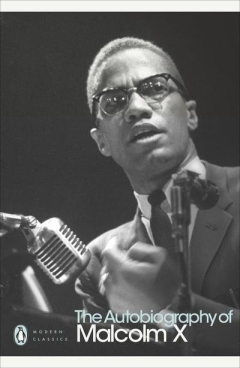

2. The Autobiography of Malcolm X

In response to accusations that he and the Honourable Elijah Muhammad incited violence among Black people, Malcolm X wrote, “It is a miracle that a nation of black people has so fervently continued to believe in the turn-the-other-cheek and heaven-for-you-after-you-die philosophy. It is a miracle that the American black people have remained a peaceful people, while catching all the centuries of hell that they have caught, here in white man’s heaven!”

This quote speaks to the rage that many Black people in the US feel right now. While there is a rich history of violent rebellions, armed protest, Black gun ownership and a commitment to self-defense, including the Deacons of Defense and Justice, the Black Panthers, Harriet Tubman, Ida B Wells, and Nat Turner’s rebellion, this current moment feels different.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) details the religious and political growth of one of the most admired and hated men in US history.

Despite being over 50 years old, the book remains relevant. Malcolm X covers a wide range of topics, including the social and psychological effects that the state can have on Black families, the role the media plays in constructing and perpetuating anti-Black Islamophobia, and the need for Muslim men to stand against sexual harassment. It also urges racial justice activists to speak in terms of human rights instead of civil rights, to show how justice movements across the globe are related.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X will be a helpful read for anyone who is unfamiliar with the everyday indignities that Black people face, both at the individual and structural level. The book shows how despite the legislative victories Black Americans won during the Civil Rights Movement, anti-Black racism in 2020 is just as prevalent as it was in 1965.

3. Black Star, Crescent Moon: The Muslim International and Black Freedom Beyond America by Sohail Daulatzai

Sohail Daulatzai’s 2012 book is a perfect complement to The Autobiography of Malcolm X. One of Malcolm X’s most significant influences to American Islam was his embrace of Black internationalism, building on the work of activists Audley Moore, Shirley Graham DuBois, and Louis Little.

Black Star, Crescent Moon uses Malcolm X as one of its primary vehicles to examine the cultural and political history of Black radicalism, Black Islam, and “the Muslim Third World” in the post-WWII era. Daulatzai highlights how Black radicals have linked their identities, art, and activism with the liberation movements in Africa and Asia because they share common struggles and common goals.

The book also helps to explain how a shared experience of state-sanctioned violence led Palestinian and Lebanese activists to tweet tips to Black Americans on how to deal with tear gas and rubber-coated bullets during the American uprisings in 2014 and again this year.

Daulatazai also explores how some Black Americans see Islam as a resistance tool, which has served as a bridge to Asia and Africa and its people, and why the US government found this dangerous. He writes: “[T]o be Black is one thing in America that marks you as un-American, but to be Black and Muslim is quite another, as it marks you as anti-American.”

Published after Barack Obama’s first presidential election in the middle of the “War on Terror,” Black Star, Crescent Moon highlights how having a “Black face in high places” does not translate to Black liberation. His critique of the post-racial feelings that Obama’s election evoked in many Americans (people believed racism had ended while President Obama continued the “War on Terror”) helps readers understand why, despite having Black mayors, police chiefs, and district attorneys, big cities like Chicago, Baltimore, and Atlanta are hotbeds for police brutality and anti-Black racism.

4. Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam by Sylvia Chan-Malik

The one shortcoming of Daulatzai’s book is the lack of attention it pays to Black Muslim women and their intellectual contributions. But this text, by Sylvia Chan-Malik, provides a much needed corrective.

Chan-Malik’s book provides an important reminder to not ignore Muslim women’s activism and that it might appear in unusual places, including photographs, poetry and documentaries.

She writes, “[A]ny historically accurate account of American Islam and US culture must necessarily make central the lives and experiences of Black American Muslims – and in this case, Black American Muslim women – as their contributions have forcefully shaped the meanings and presence of Islam in the United States.”

Being Muslim (2018) explores how Muslim women of colour in the 20th and 21st centuries have played an important role in building Muslim practices and identities, as well as shaping how race and gender are viewed in the US.

Taking a chronological approach, the book starts with the Ahmadiyya Muslim Movement in the 1920s – a minority sect who regard their founder as a prophet – and ends with a discussion of contemporary Muslim feminism in the United States.

And the book resists narratives that characterise Islam as a foreign or immigrant religion – a perspective that privileges Arab and South Asian Muslim Americans yet ignores the impact that Black Muslims, including Black Muslim women, have had on Islam in the United States, as well as white and Latina Muslim women.

Chan-Malik reminds all Muslims in the United States that they are indebted to the labour of Black Muslims, including Black Muslim women. Being Muslim emphasises that race and gender matter when discussing Islam, and this extends to our activism too.

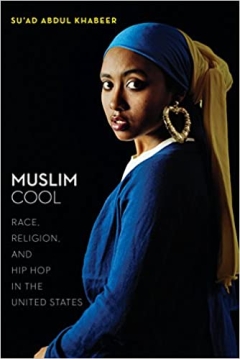

5. Muslim Cool: Race, Religion and Hip Hop in the United States by Su’ad Abdul Khabeer

Even though Muslim Cool (2016) is not a history book, it is still important because it provides an extensive discussion on constructions of race within Muslim communities in the US.

Su’ad Abdul Khabeer introduces the term, “Muslim cool,” which she defines as “a way of thinking and a way of being Muslim that resists and reconstitutes US racial hierarchies”. The mainstream racial hierarchy places whiteness at the top, Blackness at the bottom, and everyone else somewhere in between, if they exist at all.

The book challenges views of the United States as being either post-racial or only existing in a Black-white binary. Race still matters.

Abdul Khabeer argues that Blackness is central to American Islam; it shapes both individual Muslims’ and interethnic relationships amongst Muslims. This is because the US public’s understanding of Islam was first shaped by Black Muslims, including the Nation of Islam, the Five Percenters, and early Black Sunni organisations.

Muslim Cool also provides an excellent overview of the Inner-City Muslim Action Network (IMAN) in Chicago, Illinois. The non-profit organisation is a site of “Muslim cool” because of its commitment to doing anti-racism work in the local community. It provides an important model for cross-racial community building because the organisation and its volunteers are ethnically diverse, while maintaining a commitment to combatting anti-Blackness amongst Muslim and non-Muslim communities.

Many Muslim non-profits focus on the concerns of middle- and upper-class non-Black Muslims’, oftentimes limiting their activism to immigration and civil rights or to struggles outside of the United States.

While this work is also necessary, it cannot happen at the risk of ignoring the struggles that Black people, including Black Muslims, face right down the street from them. IMAN often uses hip hop and other artistic expressions to help build a bridge with different ethnic groups to reframe people’s worldview and activism to include Black liberation.

The book concludes with a discussion of the Black Lives Matter movement. Muslim Cool reveals the delicate balance between non-Black Muslims embracing Black culture (hip hop), and appropriating it. Abdul Khabeer highlights the responsibility non-Black “hip hop heads” have to the creators of hip hop: stand with them in the fight against anti-Blackness.

This discussion is useful for people of colour who are interested in supporting the Black Lives Matter movement but do not have deep ties to local Black communities, because it provides a roadmap to ethically engaging in anti-racist activism.