Photos by Kamal Shkoukani

Milwaukee’s Rohingya community celebrated the academic success of its youth and the parents who supported them at its annual festival in September.

“A major issue confronted by immigrant children and their families is the acculturation gap that emerges between generations,” writes Dina Birman, Ph.D., and Ph.D. student Meredith Poff of the University of Illinois at Chicago in research published in the Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development. As their children become socially integrated in American culture, adopting a new language, attitudes and values, immigrant parents cling to values and customs of their motherland.

“As a result, immigrant parents and children increasingly live in different cultural worlds.” This cultural gap makes family communication and mutual understanding difficult, and can lead to family conflict, Birman and Poff conclude.

Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalitions’ culturally specific domestic violence program Our Peaceful Home addressed this challenge in a two-part series offered recently, “Strengthening the Muslim Parent: How to Bridge the Cultural Ties with your American Muslim Children,” shown on Facebook Live on Dec. 15 and Dec. 22. The first program is a discussion in the Rohingya language with Rohingya educators and community leaders in Canada; the second is in Arabic with an Arab-American educator, social worker and chaplain.

Our Peaceful Home offers parenting education in multiple languages.

“One of the goals of Our Peaceful Home is not only to provide services for family members to address issues of domestic violence and abuse, but also to strengthen the family,” said MMWC president Janan Najeeb. “Strengthening the family is a result, of course, of education.

“We have been offering programs in many different languages, based on the various communities we work with,” Najeeb explained. Milwaukee likely has the largest Rohingya refugee population in the United States.

Below are highlights from Najeeb’s discussion with Rohingya-speaking guests Anwar and Zainab Arkani. Anwar is the founder and president of the Rohingya Association of Canada and co-founder of the Rohingya Language School in Ontario, Canada, the first government-recognized school for Rohingya in the world. He has been invited to speak on the plight of Rohingya refugees at the United Nations and to testify before Canada’s Parliament on several occasions.

Zainab is the RAC’s director of community development and women empowerment. She is also co-founder with her husband of the Rohingya Language School in Ontario, Canada. Together they addressed questions about parenting for Milwaukee’s Rohingya community. Answers were summarized in English and are paraphrased below.

See the full program in Rohingya and English here.

Please tell us the major challenges that you hear from students themselves?

What I hear from the students is, they say, very sadly, our parents cannot help us. They never had a chance to learn. So, they cannot help us with the homework and with other things.

How do most of them identify themselves? Do they see themselves as Canadian? As Rohingya? As Muslim?

They identify themselves by where they came from. Some of them came from refugee camps in Bangladesh, some from Malaysia or Indonesia. They prefer to tell where their birth countries are rather than where their ancestors came from. So, first of all, we have to understand why they say that they were born in Bangladesh refugee camp. Most importantly, they want to belong, to be from somewhere.

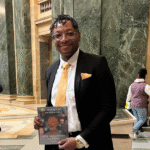

Anwar Arkani is the founder and president of the Rohingya Association of Canada and co-founder of the Rohingya Language School in Ontario.

How can parents help children learn their Rohingya identity?

We have a golden opportunity to show them the strength of our culture and our religion. For example, the Rohingya are a very generous people and we help one another. We look after each other. We have to share this value with our children.

We are not only genocide survivors. We shine. That’s what we have to tell them and they will be proud. When the parents can uphold their identity, children will be proud. If we look down on it, everything is lost.

We have to understand we are a very good people with a good historical background. We have some highly educated people, a famous nuclear scientist, professors, doctors, engineers. We should also be very proud of those of us who follow our religion and teach these things to our children so they will be happy to associate as Rohingya and Muslims.

How can we bridge the gap with children who are adopting different cultural practices (as long as they are not in violation of the faith)?

Children learn English very fast, faster than their parents. Parents tend to use the children as interpreters or translators. It gives the children the impression parents are needy without parents really recognizing the consequences. Sometimes they ask the children to answer the phone, then tell the children to say they are not home. The children learn it is okay to lie. Children will slowly lose the respect they had for their parents.

Helping children with their schoolwork can be very difficult when you haven’t had the chance to be educated yourself. How can parents encourage their children to do well in school?

Zeinab Arkani is co-founder of the Rohingya Language School in Ontario, Canada, the first government-recognized school for Rohingya in the world.

Parents need to be involved in their children’s education. Ask about school. Tell them to show you what they learned. If you make it a habit, a daily routine of about 15-20 minutes, the children will get used to it and they will become closer to their parents. Also, teach them the importance of completing their homework and respecting their teachers.

Parents may consider creating “homework clubs,” bringing children together to work on homework. They can help each other, maybe explain some things in their own language.

Some things on social media can be very useful and some dangerous and detrimental, yet many times parents are not aware of all the things that can be accessed by phone. What advice would you give parents about their children and social media?

Parents need to be aware of the many platforms our children can access on social media. If your child is alone in their room with the phone, you don’t really know what they are doing and you need to know. Parents can open their own Facebook, Instagram and Twitter accounts and follow their children. If you see them say or do something inappropriate, use the opportunity to teach them why it is inappropriate. Don’t just punish them. Give a good explanation of why it is bad.

Have them use social media in a place where you can see them. Limit screen time, whether TV or social media. Teach them the importance of doing homework first. Teach your children about dangers on social media and how to avoid them.

Education is very important to everyone, including women and girls. Yet, in some traditions, there is a push to get the girls married, which can limit their education and their ability to educate their own children. As two educated individuals, what would you say to parents about this topic?

There were obstacles back home, fear of someone coming to school and taking their daughters away. Religious scholars there sometimes said girls 10, 11 or 12 should not go to school anymore. We need to understand that is part of the bigger picture parents there faced.

Here, in Western countries where we resettled, we have chances to educate our daughters. We need to learn it is not forbidden to educate our daughters. There are educated women who are working in Bangladesh, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Dubai. Females work in government and non-governmental sectors. Many Muslims appreciate having female doctors.

How can Muslim parents be good role models for our children?

When people live together, whether husband and wife or parents and children, there will be conflicts. How we resolve those conflicts is important. We can learn the good things in American culture and if we see things in our own culture that are not good, we can distance ourselves from them. As long as we are willing to learn, we can bring good changes.