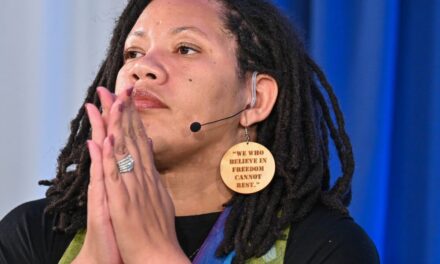

Asha Mohamud: ‘You gain so much spiritually.’ Photograph: Suki Dhanda/The Observer

A month of fasting brings both challenge and rewards. Three Muslims explain how they combine its spirituality with their busy lives

Tonight, after sunset, hundreds of millions of Muslims across the world will embark on Ramadan, the ninth and holiest month of the Islamic calendar, in which it is believed the Qur’an was revealed to the prophet Muhammad. For 30 days, many Muslims will be fasting – no food, no water – from sunrise to sunset, getting on with life while taking on one of the greatest acts of faith. Not eating, or drinking even the tiniest drop of water, is hard.

It is more difficult still in the long days of a British summer, where the morning meal (sehri) has to be eaten by 2.30am and the fast can’t be broken with the evening meal (iftar) until after 9pm. But it can definitely be done. Some will keep working out, playing football or heading to the gym, even after a day at work or school. Others will dedicate more time to meditative prayer or studying the Qur’an. As so many of us will attest, the challenge is mental rather than physical. Feeling weak or lethargic by the end of the day is common, but the body adjusts and willpower is extraordinary – as with any sort of training, fasting gets easier as you go on.

Exemptions are made for the elderly, the young, anyone who is ill, for women who are pregnant or menstruating, and for those travelling. In these cases, fasts are made by fidyah – donating money or food to those in need. Fasting during Ramadan isn’t just about resisting the temptation to eat: it also means no sex, no smoking, no bitching, no general bad behaviour in daylight hours. Instead, love, charity, kindness and prayer are prioritised. Consider it a spiritual detox.

Asha Mohamud, 20, British-Somali model, and the face of Asos’s modest fashion line. Lives in west London

The question I get asked most in Ramadan is, “You can’t drink even a sip of water?” People think that models don’t eat anyway, and so Ramadan should be easy, but that’s not true. For a start, you always end up putting on weight because your body craves heavy, greasy carbs at iftar and then you can’t move afterwards. My mum always says when we’re piling our plates up, “You won’t finish that!”

My family are from Somalia, and like other Muslim cultures we have a lot of food on the table at iftar – things like curries and samosas and fruits – and it’s a really amazing time for getting the family together.

I look after my body and always eat while I’m on shoots, so this month will be a test, but the peace you feel during Ramadan is beautiful. It’s difficult to explain, because most people can’t get past the idea of no food or drink, but you gain so much spiritually. It’s a different, calmer perspective. You put yourself in the shoes of people who live this reality every day and it reminds you to be grateful and patient.

I have been fasting since I was 11, and it has always been in the summer months [Ramadan moves back two weeks each year, in line with the lunar calendar] and during exam season. That was hard! Not the food, but keeping your concentration and focus. Alhamdulliah, I got really good grades and I’m at uni now. The last hour is the one everyone finds difficult but I cope by going to the gym. It’s not that mad – just light running and some weights. I find it a really good way to be distracted and make the time pass more quickly. I have eight siblings aged between six and 23 years old – it’s so exciting to do Ramadan with the younger ones. They don’t fast but we all love the family get-togethers and Eid. It’s so nice and special knowing that so many Muslims are doing this together – it really makes you feel strong.

Rahima Mahmut, 49, Uighur musician, activist and translator. Moved to the UK from north-western Xinjiang, where up to 3 million Muslims have been detained in “re-education camps” by the Chinese government. Lives in north London

Rahima Mahmut: ‘It’s a month of joy’. Photograph: Antonio Olmos/The Observer

Ramadan was always a month of joy when I was growing up: it was something we looked forward to. In East Turkestan – which the Chinese call Xinjiang – we had some periods of freedom with religion because there weren’t the hi-tech surveillance systems there are now.

Regardless of where we are, Ramadan is one of the pillars of Islam that Muslims try and observe. My whole family would wake up together – even younger siblings who weren’t fasting – to eat the morning meal. We would prepare it before going to bed – things like goshnan [meat sandwiched in bread], or pilau rice with carrot and lamb – heavy, oily food to keep you going through the day. Even though the heat can be very dry in my country and the temperature goes up to 40C, because of your faith, you don’t really find it difficult. The first week you feel disorientated, then like any practice you get used to it, and it becomes something you want to do: it’s a time of happiness and personal peace – you make an extra effort to make everything you can think of for the evening meal, which is always a full table.

Advertisement

In Uighur culture, we break the fast with water, green tea, and usually a fresh, light soup. Snacks and biscuits can come next and heavier food at the end. I love eating leghmen – noodles handmade from scratch – lamb and vegetable korma, and steamed or fried dumplings.

I left my home city of Ghulja in 2000 to come to London for my masters degree, and I haven’t been able to go back. All my family is there. My phone calls are banned – we can’t speak. The last contact I had was in January 2017. My brother was emotional and said we had to leave each other in God’s hands. I don’t know if my family are detained in camps or in prison. My mother died in 2013 when I was battling breast cancer.

We are the most persecuted Muslims: watching the news about what the Chinese government is doing to my people causes a lot of anxiety and it really pains me to think my beautiful siblings are having such an important holy month taken from them. My father was an imam. Faith is the one thing that keeps Uighur people going, and to have that taken from you and suffer cultural genocide is very painful. So in recent years, even though my son and I still attend iftar get-togethers with the Uighur community here in London, Ramadan has become a sad month. I cannot imagine how my family and friends back home cope.

Muddassar Ahmed, 36, British-Pakistani public affairs consultant. Lives in east London

Muddassar Ahmed: ‘My wife and I are being more mindful and healthy.’

We always had the classic Pakistani Ramadan growing up in east London – the food is carb-heavy: Mum will make samosas, curries and pakoras, plus lots of sweets and dates and fried things.

My wife and I are making our own traditions, trying to do things differently – to be more mindful, and healthier – so we’re preparing lots of soups, vegetables, dals. We host iftars too, and invite non-Muslims to join us – it’s a wonderful time to help promote a better understanding of what Islam is about.

I have just come back from a pre-Ramadan retreat in Devon that I organised, which was a way for Muslims to come together and prepare physically and spiritually for the month ahead. I’m thinking much more about the environment and sustainability – I’ll be going pescatarian this month and avoiding the food coma you usually get at night. When you’re working, you just can’t afford to do that to your body: it unsettles you.

Luckily, I work in an office with other Muslims and we alter our hours. Usually I travel for work every other week but I’ll not be doing that this year.

The most difficult thing for me is waking up in the morning and not having coffee – caffeine withdrawal is tricky, because I usually get through three to four cups a day.

Mostly, I will be making a concerted effort to be more present in prayer, more present and mindful when I’m eating, and combining spiritual practice with the modern wellness movement.

The holy month: all you need to know

- Ramadan, the ninth and most sacred month for Muslims, begins today and ends for most on the evening of Tuesday 4 June.

- The Islamic calendar is based on the lunar cycle, in which 12 months add up to 354 days.

- This is why the first day of Ramadan moves back by 11 days each year and its conclusion, Eid, is announced on sighting of the moon, which varies from region to region.

- Mosques issue a schedule for those fasting according to local sunrise and sunset times. In London, the first fast begins at 3.43am and ends at 8.33pm, and the final fast begins at 2.48am and ends at 9.14pm.

- Fasting is one of the five pillars of Islam, the other four being testimony of faith, daily prayers, charity and the Hajj – making a pilgrimage to Mecca.

- Muslims see Ramadan as a time for recharging their faith with extra focus and discipline in prayers and the teachings of the Qur’an. Once the month of fasting is complete, there will be three days of celebration – the Eid al-Fitr.