Photo©:

Initiative on Islam & Medicine

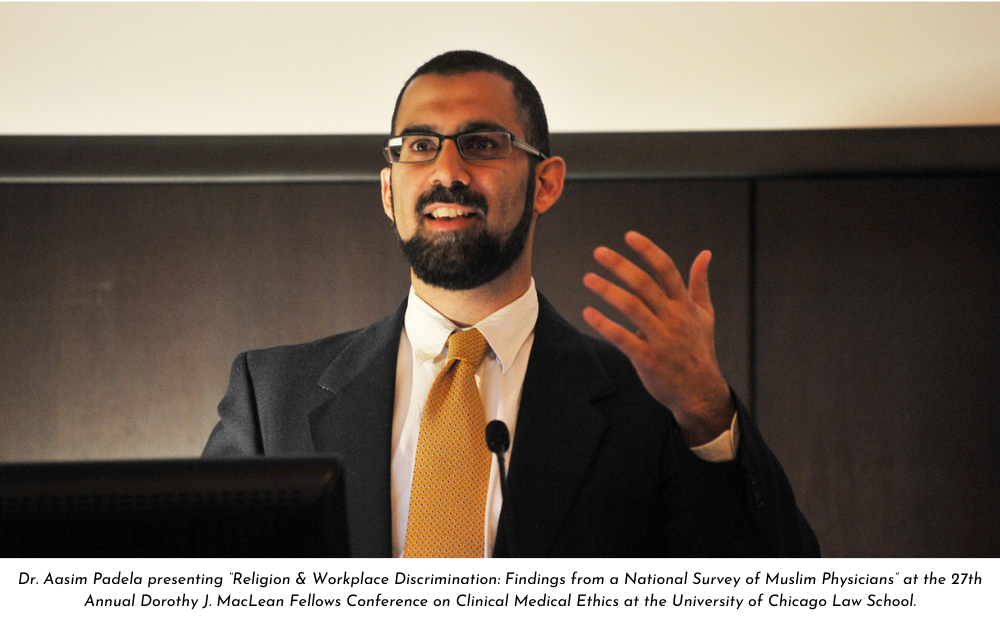

The Medical College of Wisconsin’s new vice chair of research and scholarship in the Department of Emergency Medicine, Professor Aasim Padela, M.D., has a history of hiking into uncharted territory. An academic Daniel Boone, he explores research domains that do not yet exist.

Dr. Padela’s multidisciplinary research clears new fields that unite ethics, medicine and religious studies. A skilled researcher, he uses a range of tools from community surveys to assess healthcare disparities to narrative discourse analysis to consider how Muslims are portrayed.

In his “elevator speech,” Padela explains, “I use Muslim Americans and Islam as a model to study how religious identity impacts health behaviors and healthcare experiences, as well as the professional identities of doctors and their practice. I also explore the bioethical guidance Islam offers to patients, providers, policymakers and religious leaders.”

Now, at 40, with wisps of gray in his beard, Padela says it is time to lead others into the clearing he has staked out in the wilderness. His move to MCW in September marks this shift in his career path.

A defining moment

Padela is the son of immigrants who came to America in the 1970s from Pakistan for postgraduate studies. He was born in New York, the second of four siblings. In May 2001, Padela, then 20 years old, graduated from the University of Rochester with dual degrees in biomedical engineering and classical Arabic language and literature.

“Our household was very religious,” he recalled. As a young man, “I was very comfortable with my identity as a Muslim. I had a degree in classical Arabic. I had done some seminary studies and had studied abroad in Egypt. I had lived in Pakistan for a while. I had a long beard and wore a kufi all the time.”

Padela calls 9/11 “the inflection point” of his life. “Let me tell you the story,” Padela said. “I am a first-year medical student at Weill Cornell Medical College, looking forward to becoming a physician. I have had EMT paramedic training. I am in Manhattan, at Cornell, on the Upper East Side.

“After the first class, we have a break. So, I go outside and some people say a plane hit the World Trade Center. We go into class a little after 9 o’clock. The deans of the medical school are coming into the auditorium; we don’t know why. We didn’t have cellphones at that time. Someone says a second plane just hit the second tower and the first building has gone down. The dean says go home and call your families. Classes are cancelled.

“Immediately, I went to a friend’s dorm room to see the TV and we saw the second tower going down. I thought, what can I do? I can pray and I can do service. I went down to the emergency department and asked, Can I help? They lined us up and put us all in different teams. But in four hours only two people came in.

Dr. Aasim Padela at the 5th International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Health, Culture, and the Human Body in Istanbul, Turkey, in 2018.

“I talk to my friends and say, ‘Let’s go down to Chelsea Piers to do triage.’ I tried to get on the MTA (Metropolitan Transportation Authority) bus, but the doors didn’t open for me. When I tried another MTA bus, the doors didn’t open. Then it clicked. I realized that everyone was worried because I was visibly a Muslim. I knew then that who Muslims are in this society was going to change forever.

“The next morning, the dean of the medical school called a town hall meeting just to hear people out because people are traumatized. I remember sitting in that class with the 110 or so medical students and someone makes the comment, ‘Now Americans know how Israelis feel every day with Muslim terrorists trying to disrupt their peace.’

“I was one of two Muslim students in that class. I got up and left the room in front of the auditorium. Later that day, the dean said to me, ‘Aasim, you need to know that the patient – doctor relationship is a place where you can inform understandings. A good doctor needs to know about his patient and a good patient needs to know about their doctor. Two worldviews meet there. You can decide whether you’ll use that to build bridges of understanding between who you are and what your faith means or not.’

“That leads directly to what I do now. My entire scholarly enterprise comes from that day.”

Setting out on his own

Medical school was the grueling first leg of Padela’s journey, “a slog for everybody,” he said. One highlight was a month-long elective course in his fourth year.

“Cornell had started a medical school in Qatar. I wanted to go there and do a study on Islamic medical ethics. I would be in a Gulf Muslim country and they were thinking about how to adopt a medical oath that would respect Muslim cultural and religious tradition. But going there for a research elective was a different matter; there were sensitivities on both sides.

“After a hard-fought battle, I was able to go,” Padela said.

As part of his research elective, Padela wrote a paper on Islamic medical ethics. “I read everything, literally everything, written in English on Islamic medical ethics.

“The idea was I wanted to help the medical students there feel secure in what their tradition says. I was trying to be a cultural liaison as I was literate in the Islamic tradition.”

Padela graduated in 2005 and was matched for residency at the University of Rochester in emergency medicine.

“Fast forward to my second year of residency, when you start thinking if you want to do a fellowship or if you want to specialize in something. That year I did a research project in which I interviewed Muslim physicians to understand how their faith identity intersected with the practice of medicine. I wanted to see the points of conflict.”

Dr. Padela discussing Islamic bioethics at the Conference on Health-related Issues & Islamic Normativity at the University of Hamburg, Germany.

Two research-oriented faculty members let Padela know he had written “a very good paper.” They recommended he consider doing a degree program in his fellowship that would give him skills to do research on his own.

Later another professor told him about the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program. “He said if you want to get research skills, this is the top program in the world and they will fund your studies. I wasn’t completely sold on research, but figured it wouldn’t hurt to apply,” Padela said. “I proposed to study health disparities among Muslim patients and Muslim providers.”

“I was asked in one interview what I thought the biggest barrier to my getting into the program. Everyone has good grades, letters and project ideas. I said the biggest barrier will be whether they want to fund a Muslim American or not, especially because I wanted to do research on Muslim Americans and nobody does that work.” Padela was accepted into the program at the university where that interview was held, the University of Michigan.

Two years later, the chair of the committee that had selected Padela pulled him aside at a conference to tell him, “‘I had to advocate very hard to have you accepted because you are doing original work. No one else in the country is doing this.’”

Padela was in the program at the University of Michigan for three years and earned a master’s degree in health and healthcare research. “I did all these projects on Muslim Americans. It was a great intellectual environment and my emergency medicine chair and I got along very well.” Padela was offered a faculty post but was recruited by the University of Chicago and “charmed by the idea that I would have a piece of myself in the divinity school, the ethics center and the medical school and would be able to create a program.”

Along the way, Padela married and had four children. He had met his future wife when he was an undergraduate in Rochester; they married when he was in medical school and they had their first child when he was in his second year of residency. A teacher, his wife decided to pursue her doctorate. “So, while we were moving, she was pursuing her studies. In Michigan, we had another child. She finished her degree. It took her 10 years but she was able to do it wherever we were,” he said. Now their children are 13, 11, 7 and 5 and his wife does educational consulting work.

Blazing new trails

In his nine years as an associate professor of emergency medicine at the University of Chicago, and a faculty member at its MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, Padela joined a group from both medicine and religious studies who were exploring the intersection of religion, ethics and medicine in depth. He enjoyed the multidisciplinary opportunities he was able to create as the director of the Program on Medicine and Religion, and he founded an interdisciplinary platform for research, dialogue and education, the Initiative on Islam and Medicine.

“At the core, my interest is at the intersection of two fields – the Islamic tradition and biomedicine. That is the scholarship I pursued for some 15 odd years,” Padela said.

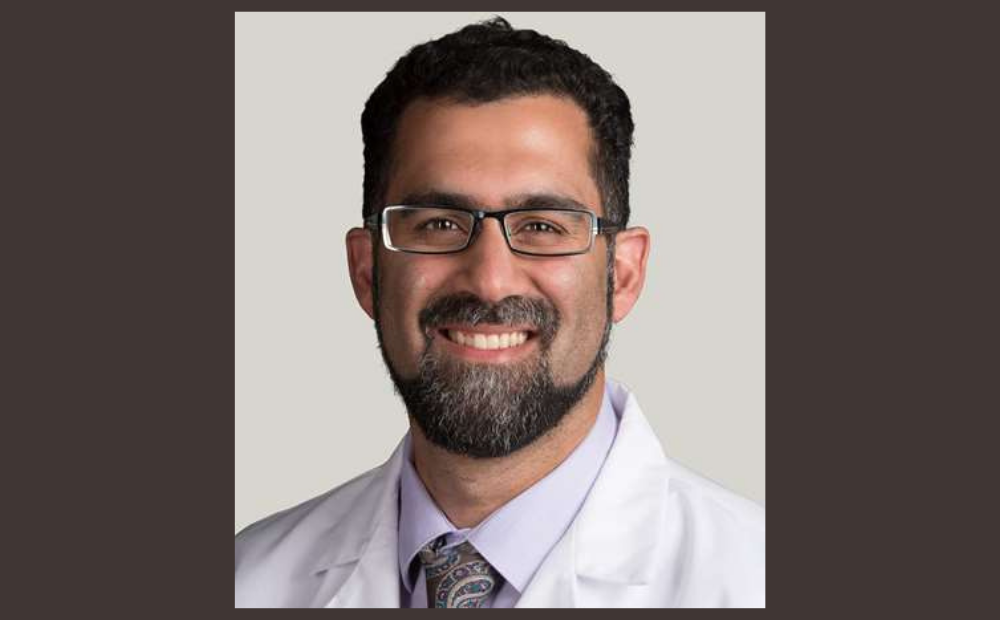

Photo © Medical College of Wisconsin

Padela’s more than 100 peer-reviewed research articles and book chapters have looked at issues like organ donation, healing, genetic engineering and withdrawal of life support through an Islamic lens. At the same time, he has been assessing health disparities in the Muslim community by considering such topics as the impact of the Muslim ban executive order or beliefs about modesty on healthcare utilization. Or the efficacy of mosque-based education on medical issues. His work has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today, the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post, National Public Radio, BBC and CNN. He has even been on the speaking circuit with celebrity physician Dr. Oz.

The challenge has been funding. “If there is no money, there is no mission,” Padela said. “The reality on the ground is, if you are an academician in medicine, there are two ways you can get funded: you can do clinical work or you can pursue grants and endowments so that your research and educational enterprises are paid for.”

“If within that sphere, you are doing Muslim health research, there is almost no money. My focus has been on two domains: I look at Muslim health and healthcare disparities and I look at Islamic bioethics. There is no institute interested in looking at Muslim healthcare disparities per se. There are no foundations that are focused on Muslim Americans as a strategic priority population.

“The way the United States looks at disparities are racial, ethnic and sexual orientation. We do not look at disparities of religious communities. That is the mission I have been trying to get people to understand. There are disparities and we have to look at them. But they are not the first, second, third, fourth, or fifth line of priority for funding.

“And Islamic bioethics doesn’t exist as an academic field. When you think about bioethics centers in the Western world, even in the Muslim world, they are focused on secular bioethics. Religious bioethics is sometimes allowed but, when religion is entering the conversation, it is predominately Christian Catholic modes of thinking. There are no centers for Muslim bioethics in the world.

“So, even now in my academic career, I have to justify why I am writing about the Muslim population or why I am drawing on Islamic precepts,” Padela said.

“Our Muslim community has not yet risen to the idea that we have to build scholarly foundations to address our own healthcare needs or to have academic enterprises that analyze issues, such as we’ve just seen with the COVID vaccination, from a Muslim perspective. We need to give voice to those scholars who can do that. We need to coalesce centers and institutions and funders and research centers around that.”

Padela has been leading that charge and is co-editor on two books coming out soon on that topic. But there is a problem, he said. “Every few years, the challenge would be to get the next grant and then the next. Being as gray-haired as I am now, I can’t live like that all the time.”

Paving the way for others to follow

With his move to the Medical College of Wisconsin in September, Padela’s focus has shifted from blazing trails to building roads.

“Research is a part of my life but not the only thing I do,” he said. “I have crossed that bridge and been successful. I’ll continue to do research but there are other things I want to pursue in the academy.”

With an eye to developing the next generation of researchers who can do research on Muslim American communities or Islamic bioethics, he is focused on creating opportunities for the scholarly enterprise through emergency medicine research and MCW’s Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities. Being an administrator brings “new challenges and using a new skill set. That is part of the attraction as well.”

At MCW, Padela is mentoring five medical students “to increase the awareness that they can do this line of work. I have models I deployed in Chicago and other places that I would like to help junior researchers implement.

“I see myself in more of the thought leader, mentor role. I will do my own research in the community when we open up and I will give other people opportunities to run with it. They will learn skill sets and be able to do their own projects. I look forward to being a coach, mentor, and advisor.

“On the Islamic bioethics sphere, I have two books coming out in the next two months. I’m writing another one. I would like to be able to complete those projects as a service to the academy and the next generation of folk thinking about this domain. That is the work I want to pursue.”

Ultimately, these efforts serve the greater community. “It helps increase awareness of healthcare disparities and consider how we can help the healthcare system be more culturally sensitive, how we can have better inclusion and accommodation of religious identity.

“I’m in the academy because I want to generate new knowledge. Hopefully, it will be beneficial.”