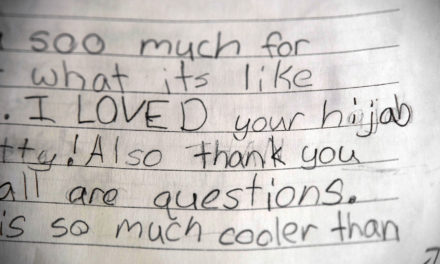

Photo by Kamal Moon

Fatoumata Ceesay, M.D. (third from the right) poses with fellow MMWC board members at the 2023 gala. From left to right: Aishah Aslam, D.O.; Hana Alqam, Ph.D.; Sahar Kayata, M.D.; Janan Atta Najeeb; Soniya Yunus, J.D.; Hanadi BuAli, M.D.; Dr. Ceesay; Nadia Alkhun and Ream Bahhur.

When Fatoumata Ceesay, M.D., of Mount Pleasant, became the second board president of the Milwaukee Muslim Women’s Coalition, “she jumped into the role immediately,” said MMWC founder and executive director, and first board president Janan Najeeb. “Her commitment to the organization is apparent.”

Ceesay was selected to be MMWC president when the organization separated the duties of the executive director and president last year. Najeeb officially served in both roles for 14 years, since MMWC became a 501c3 nonprofit organization in 2010, and unofficially since MMWC began in 1994 as a women’s circle and speakers bureau that aimed to dispel stereotypes of Muslim women.

“I didn’t lobby for the position but wasn’t hesitant about taking on the role,” Ceesay said. “Nobody tries to fill Janan’s shoes, but I saw the opportunity to learn a lot and Janan would be right there. I’d have a great teacher.

“I saw it as an opportunity to grow and also contribute to something worthwhile and meaningful. It’s hard to imagine an organization with a more positive impact on Milwaukee than MMWC.”

Although, as she noted, Ceesay has “never been president of anything before,” she believes in taking on challenges and jumping into them wholeheartedly, she told WMJ. With this approach, she achieves important goals and contributes significantly to the lives of others—including graduating from medical school while raising a son as a single parent and becoming a board-certified pediatrician, working at one of the most prestigious children’s hospitals in the world.

Along the way, she’s also been a true friend. Her closest friends think of her as family and say she is the one they know will be there when they need her, and even when they don’t—always ready to hop on a plane for a fun vacation together, or just hang out at home and share a few laughs.

Through it all, she’s faced what may appear to others as insurmountable personal challenges. She shares those with only her closest associates. “I’m a private person,” she said to the Wisconsin Muslim Journal before hopping to the next topic—her vision of ensuring every child in The Gambia has access to high-quality medical care and her plan to make it happen.

That would be no easy task for any organization. That doesn’t stop Ceesay.

“I’m a firm believer that Allah (God) will put on you only what He knows you can handle,” she told WMJ, while answering questions about her accomplishments. “I always initially feel a little bit overwhelmed. But I always bounce back quickly. I say to myself, ‘Allah is speaking to me. He wants me to learn something out of this. He wants me to have a better relationship with him and benefit not just myself but the people around me. This is an opportunity so just take it.’”

A leap of faith

Always direct and matter of fact, Ceesay decided to travel from The Gambia to the United States in 1989 for college. She knew someone from home who studied at Fairmont State College in West Virginia, so she went there. “I came to school by myself,” she recalled. “I remember flying into New York and seeing the skyline. My own little African girl inside me was thinking, ‘Yeah, I’ve arrived.’

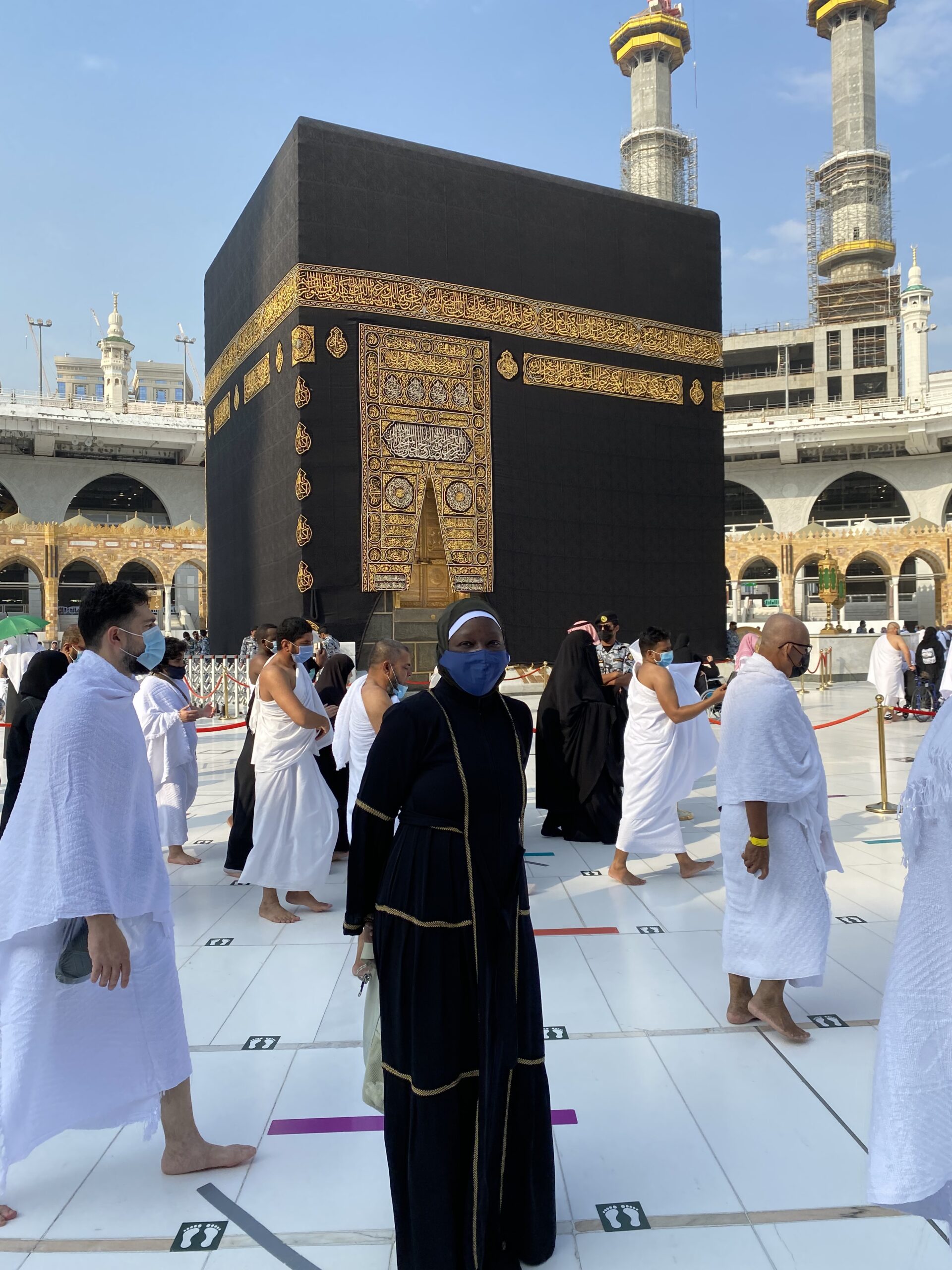

Fatoumata Ceesay, M.D., during an Umrah pilgrimage after the COVID pandemic.

“My mom and dad had arranged for somebody to meet me at the airport and help me book another flight to West Virginia. I looked around for an hour but didn’t see anyone so I bought my own ticket and got on a flight to Pittsburgh. I didn’t want to wait. I thought, ‘I’m just going to do this.’”

The college dean picked her up in Pittsburgh, which Ceesay noticed was also a big city of glass skyscrapers. As they drove through the mountains of West Virginia, with not a building in sight, Ceesay turned to the dean and asked, “Are you driving me out of America?”

Ceesay received the first scholarship for an international student given by Fairmont College. She graduated with a Bachelor of Science Degree in biology.

Then work and family life began.

“I actually took 10 years between my first degree and going to medical school,” Ceesay said. “I got married and had my son. I worked for a while as a chiropractic tech and as a paramedic but I always knew I wanted to go back to medical school.

“One day I just finally said to myself, ‘Stop it! You’re never going to be happy unless you study medicine. Just go do it.’ So, you know what I did? I just put my head back together and dug in.”

She studied for and took the MCAT. Then she enrolled at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine in northern Chicago.

From cold to colder

Ceesay was offered a residency in Chicago but also had the opportunity to interview at Children’s Hospital.

“I told this story to our residency director who just shook their head,” she said. “On the way to Milwaukee, I turned around three times. I turned around in Gurney and again in Mount Pleasant and again right before reaching downtown.

“All of the sudden, I’m asking myself, “Why am I doing this? I’m trading cold for colder.

“I can stay in Chicago and just do my residency there. Then, finally, I thought, ‘Just go. It’s a free hotel, free food. Just go.’”

When Ceesay got to Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, something told her, ‘Pay attention,’” she said. “Something special is going on here.”

She noticed the diverse staff she encountered. Ceesay asked the director of admissions for the residency program, “Why is everybody here from somewhere else?

“He chuckled and said, ‘Well, if you come here, you will know.’”

“I interviewed with, I learned later, the ‘God of pediatrics.’ But I didn’t know who he was. I walked into his office and figured he was a big cheese because he had a personal assistant. Nobody else had a personal assistant. He was wearing a Grateful Dead t-shirt and a yamaka.

“I’m shooting the breeze with him and just having a grand old time. After the interview, we met with the residents already in the program. They asked, ‘Who did you interview with?’

I had forgotten his name so I said, ‘A guy in a Grateful Dead shirt.’ The whole room went quiet.

“The chancellor? The one who wrote all the pediatric textbooks?

“’Oh no!’ I thought to myself. “I had made no effort to impress him. I was just myself.”

When Match Day came, the day when medical residents are placed for supervised practice, Ceesay matched with Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin. She did her residency, graduated from the Medical College of Wisconsin in 2007, and went on to work full-time as a pediatrics specialist at Children’s Hospital for over 16 years.

She always thought about leaving Wisconsin for a warmer climate since meeting and marrying Steed Welch, five years ago, she said she is here to stay.

“It’s a great place to be,” Ceesay said about Milwaukee. “I have grown so much being here. It’s an easy place to fly in and out of if you want to travel and whatnot. I’ve traveled in all the world from here.”

She recently transitioned into working in administrative medicine and now works from home part-time. During this professional transition, she found she had time to devote to community service and building her long-held dream of creating a system of medical care for children of The Gambia.

Leading the board

When Ceesay was chosen to lead the MMWC board, she had only been on the board for about seven months. Najeeb had confidence she was the right woman for the job.

“She’s very thoughtful. Clearly, a team player,” Najeeb said. “She gets along very well with people. She brings people together. She is a professional who has experience in dealing with many individuals from all walks of life. She brings that skill set, which is very important when thinking about all the programming we are doing.”

Photo by Kamal Moon

At the annual MMWC Behavioral and Mental Health Conference in September, Fatoumata Ceesay, M.D., chatted with conference organizer Mohamed Amine Ouzif.

MMWC operates four key projects: Our Peaceful Home, a culturally sensitive domestic abuse program; Wisconsin Muslim Journal, a statewide, twice-weekly online newspaper; Islamic Resource Center (a culture center and Islamic lending library that hosts programs for all ages; and the Milwaukee Muslim Film Festival.

Additional projects have developed as community needs evolved. They include the IRC Book Club and the MMWC Networking Brunch, which both attract interfaith participants, a speakers bureau, children and youth programs, a leadership program for young women, programs and activities developed for refugees. In conjunction with the Medical College of Wisconsin, MMWC hosts an annual conference for mental health professionals that educates participants on culturally specific issues related to treating Muslim patients.

“I want to be part of building the structure that gets us to where we want to be,” Ceesay said. “I want to be instrumental in helping us achieve all we set out to achieve.

“There is no other organization like MMWC. It does amazing work in our community. The final goal is to build a model that can be replicated anywhere else in the United States. I want to be in the group of women that help facilitate that and make it happen.”

Ceesay also admits that her role on the MMWC board is also “a learning opportunity to springboard onto my own foundation. I can modify and apply what I learn to launch my own foundation.”

Building the dream

“Let me tell you about how this came to me,” Ceesay said to WMJ. “It’s been about 20 to 25 years in the making.

“I feel very privileged that Allah has blessed me to be able to come to America and to follow my dreams and study, and be a physician. I always wondered, “Why am I being given this opportunity?

“It’s ingrained in me from my background, my upbringing and also just from the fact that I know that to whomever much is given much is expected, a desire to give back. I’ve always wanted to go back home and do something in the medical field.”

Fatoumata Ceesay and her husband Steed Welch

In U.S. cities, several pediatric offices can be found in almost every zip code, Ceesay noticed. “In The Gambia, within the capital city, there is a little bit of access to medical care but in small towns and villages, women walk 10 or 12 miles to get to a clinic to have their children seen.

“It’s always been in the back of my mind. What can I do about this? And, you know how it is, living in America, you have obligations to take care of, so important things get on the back burner.”

In 2019, a friend Ceesay went to high school with got in touch with her. Her 14-year-old son was very sick—so sick he was very weak and couldn’t walk. He had missed a lot of school. She asked Ceesay if she could send her his medical paperwork to take a look.

An ultrasound had been done in January and they saw something on his liver. They advised the family to follow up. When he finally went back, there were lesions everywhere in his liver and elsewhere in his body. They suspected cancer and, at the time, the hospital was not equipped to treat him, Ceesay said.

Across the border in Senegal, chemotherapy was available. “My friend, myself and a Senegalese friend pooled our resources and decided to have the child taken to Senegal’s capital, Dakar, where he could be evaluated and treated,” she said. During the five-hour car ride, he passed out. They ended up in a village hospital where they gave him IV fluids and oxygen. “It resuscitated him and the family thought he was better, and decided to turn around and go back to The Gambia. About a month later, he passed away.

“As sad as this story is, it is not unique,” she said. “I’ve heard so many stories about kids not getting adequate medical care. Sometimes there are complex health issues, but more often, it’s because of a lack of financial means. Families have to make difficult choices. Do we spend this money and go see a doctor, or do we feed the rest of the family? But this was the first time it was this close to me.

“I said to myself, ‘Well, this is an opportunity. This is something I can do.’ At this point in my life, I’m able to pick this up and run with it.’”

Ceesay has given years of thought to setting up a foundation to address the problem of access to medical care in The Gambia. Since moving to administrative medicine, she has found the time “to set it up from the ground up,” she said. “The goal is that no child in The Gambia will die because of a lack of medical care,” she said.

Maram Bobb Children Foundation was registered in Wisconsin in July 2023. It is also in The Gambia. She has established an impressive board of directors from around the world and is forming relationships with the Ministry of Health in The Gambia and with clinics and hospitals there to help identify children at risk because of a lack of follow up, as was the case with her friend.

“There are many reasons people don’t follow up. Some don’t have the financial means. Some can’t navigate the resources. Those are the children that will be referred to our foundation. We will sponsor them and pay for their medical care. We’ll have boots on the ground to help them navigate the healthcare system. We will do that by raising money in the United States and other Western countries.”

With much of the groundwork done, Ceesay, as those who know her expect, eager to jump in.